‘Postcard from the future’: Virus and solar cause record fall in CO2.

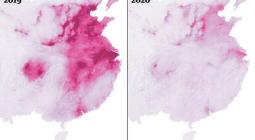

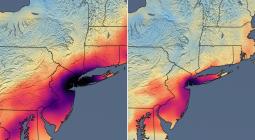

Business interruption during the coronavirus crisis has caused a 14% fall in demand for electricity in Europe over the past month. Combined with record solar output, this has caused a 39% drop in related CO2 emissions, according to a new analysis.

The sudden drop in emissions was mostly due to interruptions at coal and gas power plants, which were switched off during the crisis to match falling demand for electricity, according to a fresh analysis by Ember, a climate think tank.

The most dramatic reductions in coal-fired electricity were registered in Germany, where lignite generation fell by 55% and hard coal by 65% over the last 30 days.

Combined with record levels of renewables – in particular solar power – this resulted in an impressive 39% drop in CO2 emissions from the electricity sector across the European Union and the UK, said Jones, who published his research on Carbon Brief.

“Across the EU27 and UK combined, wind and solar reached a record-high 23% share over the past 30 days,” Jones wrote, with solar generation rising by 28% compared with the same period last year, due to new installations and a sunny April across Europe.

The research by Ember echoes similar findings by the International Energy Agency (IEA), which predicts an 8% fall in global emissions this year.

The IEA’s Global Energy Review 2020 report, published on Wednesday (29 April), projects that global electricity demand is set to fall by 5% in 2020, the largest decline since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Abundant renewables and negative prices

What makes Ember’s analysis stand out is that it looks at the parallel rise in renewable electricity output. According to Jones, the 23% share for renewables in electricity was the highest ever for any 30 day period, up from 18% in the same period last year.

This record level of renewables production offers insights into what a zero-carbon electricity system could look like – a kind of “postcard from the future,” Jones said.

“The data from this unprecedented crisis shows that electricity systems can operate smoothly and reliably, even when variable renewables such as wind and solar meet higher shares of demand, which had not been expected until at least 2025,” Jones wrote.

But there are hard lessons too. According to Jones, this “postcard from the future” of the electricity system also highlights a lack of flexibility, with many power plants unable to switch off in response to low or negative market prices.

“Electricity systems must become much more flexible to absorb higher levels of wind and solar in the future, including through ‘responsive demand’ that can shift to when power is cheap,” he said.

Electricity markets in particular have shown signs of rigidity. As supply outstripped demand, there was “a marked increase” in the frequency of negative prices on the electricity market, Jones said.

“There were negative prices simultaneously in 10 EU countries at lunchtime on Sunday 5 April. Despite this, some fossil-fuelled power plants continued to generate electricity, indicating a lack of flexibility,” Jones wrote.

The most inflexible fossil plants are lignite-fired coal generators, which continued operating on 5 April in Germany, Bulgaria and the Czech Republic despite the negative prices, Jones said.

While nuclear plants tend to be relatively inflexible, French state-owned utility firm EDF was able to reduce output from its nuclear fleet by one third – from 37 gigawatts (GW) to 25GW – when negative prices hit, Jones said.

But even renewables showed signs of inflexibility, Jones said, although they are technically capable of responding quickly at times of system stress. This is often due to outside constraints, such as production subsidies, he suggested.

30 April 2020

Euractiv