Ocean scientists call for global tracking of oxygen loss that causes dead zones

Scientists from six continents say a monitoring system could help protect coral reefs and fisheries around the world

A team of ocean scientists from six continents have made an urgent call for a global system to track the loss of oxygen from parts of the ocean and coastal waters that causes dead zones, where almost nothing can live.

Ocean heating caused largely by burning fossil fuels is making the problem worse, experts say, with serious consequences for communities, fisheries and ecosystems around the world.

Fifty-seven scientists from 45 institutions in 22 countries have laid out the urgent need for the global monitoring system, which they say could help protect ecosystems such as coral reefs and fisheries around the world.

Dead zones with low or no oxygen can last from days to months in so-called hypoxic events that can kill fish, plants and crustaceans.

Coastal events are usually triggered by extra nutrients running into estuaries, and are made worse by warming waters.

There are hundreds of hypoxic zones on coastlines around the world, with some evidence oxygen levels in parts of the open ocean are also falling.

Prof Karin Limburg, of State University of New York, is one of the scientists calling for a global system to monitor ocean oxygen, to be established under the UN.

“There is a pressing need to document and predict hypoxic episodes and hotspots of low oxygen in order to take protective actions for aquaculture, put in place precautionary measures for affected fisheries, and monitor the wellbeing of important fish stocks,” Limburg said.

“Without this understanding, we are in the dark about impacts that have large economic-ecological implications.”

Prof Jodie Rummer, of James Cook University, is a co-author of an article to appear on Sunday in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science laying out the case for the monitoring system.

“Everything needs oxygen in the water. Most life in the ocean is not hypoxia tolerant,” Rummer said.

“These problems are getting worse because we are not solving the problems of nutrient run-off and our waters are continuing to warm.

“We still don’t know the long-term implications of these problems that affect fisheries and aquaculture that feed human populations.”

Rummer is coordinating a new project with Unesco to look at the affects of lower oxygen levels on the world’s sharks.

There is emerging evidence, she said, that corals in tropical areas are also at risk from low-oxygen events.

There is already an array of equipment taking ocean oxygen measurements, including underwater gliders, free-floating instruments and sensors.

But there needs to be more and the data is not openly available or standardised, the scientists say, making global assessments and research harder at a time when the problem is becoming urgent.

Prof Marilaure Grégoire, of Belgium’s Liège University, and the lead author of the article, said: “Currently, the quality and availability of oxygen data across international databases do not allow accurate estimates of long-term oxygen declines.”

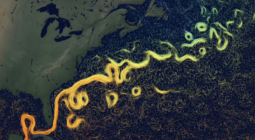

One of the best-known low-oxygen zones is a vast area that now forms every summer in the Gulf of Mexico, stretching out from the mouth of the Mississippi river. The largest dead zone formed in 2017 across 23,000 square kilometres.

Adding nutrients to coastal waters feeds bacteria that consume oxygen, causing levels to drop. But warmer waters also increase the metabolic rate of living things, meaning they need more oxygen to survive. On top of that, as water temperatures rise, the amount of oxygen available falls.

Australia has experienced many hypoxic events, triggered by nutrients and pollution from degraded soils, roads and farms running into estuaries after heavy rain.

The extra nutrients can cause a burst in bacterial growth in the water, stripping out oxygen. In some cases, fresh water forms a layer on the surface that stops the water mixing, creating dead zones underneath.

Almost all living things in the ocean, lakes and waterways need oxygen, said Prof Perran Cook, of Monash University in Melbourne.

“What controls the oxygen is temperature,” said Cook, who was not one of the authors of the paper, but said he strongly agreed with the need for a global monitoring system.

He said: “There’s a very real concern that oxygen is decreasing in our waters and that has negative effects for the health of fish and the ecosystems.

“In the same way that we invest in climate change monitoring to help us understand what’s happening, it is really important to know waters are changing because of human influence.”

One study has found waters in estuaries along more than 1,100km of the New South Wales coastline warmed by more than 2C between 2007 and 2019.

He said areas in northern New South Wales and south-west Victoria – such as the Gippsland Lakes and Anglesea River estuary – had seen hypoxic events, but the causes were not always the same. Areas of the Derwent river estuary in Tasmania also experience hypoxia regularly.

The aquatic ecologist Dr James Tweedley, of Murdoch University in Perth, has studied the effects of low oxygen on estuaries, including a three-month-long event in 2010 in the Swan Canning estuary after a storm.

He said hypoxic events in estuaries could have severe knock-on effects because they were nurseries for crabs and fish, and their larvae find it hard to escape when oxygen levels drop.

“We now have technology that can record what’s happening in the ocean,” he said.

“Having [a global system] would be really valuable because it’s fundamental to modelling of climate change and global change. We need to understand this on a global scale.”

19 November 2021

The Guardian