Mideast Petro-States Look Past Oil Rout to Chase Solar Power.

Some of the Middle East’s biggest oil producers are pushing into solar energy even amid the rout in crude prices.

Cheap crude used to deter investment in renewable energy in countries that depend on oil sales for revenue. Today, solar projects cost only about a 10th of what they did a decade ago, thanks to more affordable equipment and better technology, according to research by BloombergNEF.

The Middle East’s first forays into renewables faltered when oil prices dropped or official priorities shifted. Solar programs that Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi embarked on a decade or so ago would have required tens of billions of dollars and never got far off the ground. Since then, governments have found partners to help shoulder costs, and in spite of potential delays from the coronavirus, their solar ambitions are gaining traction.

"Solar power is the cheapest kilowatt-hour in the Middle East,” Benjamin Attia, an analyst for power and renewables at consultant Wood Mackenzie Ltd., said in a telephone interview from Boston. New projects in the region rely on private funding, rather than government spending, and are therefore “insulated from headwinds” of lower oil prices, he said.

Electricity demand in the Middle East has risen by about 6% a year on average since 2000, according to the International Energy Agency. Whereas countries in the region used to rely mostly on power stations fueled by natural gas or crude, solar plants can now meet all of their likely growth in demand, said Robin Mills, founder of Dubai-based consulting firm Qamar Energy.

Wind and solar plants generate only about 5% of the power in the Middle East and North Africa, according to Bloomberg Intelligence, and crude-producing countries in the Persian Gulf are among the world’s biggest emitters per capita of greenhouse gases. An analysis in the Guardian newspaper in October reckoned that oil from state producer Saudi Aramco was responsible for more emissions than any other single company.

“The Middle East has planned for a long time to reduce its dependence on oil,” said Jenny Chase, an analyst at BloombergNEF.

Prices for benchmark Brent crude have slumped 52% this year, falling far below levels that most governments in the region need to balance their budgets. The coronavirus, meanwhile, is delaying the construction of solar facilities in Abu Dhabi, Jordan and Qatar, and many of these projects will “spill over into next year,” Attia said.

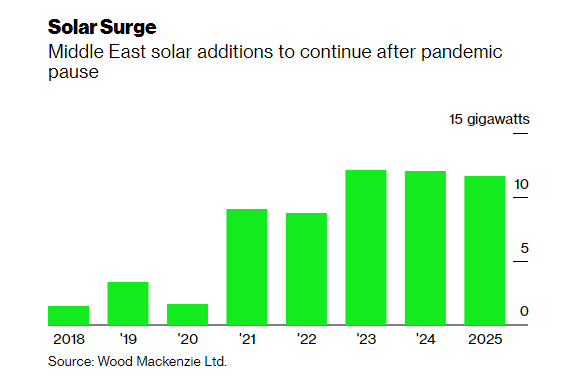

Despite uncertainty about the pandemic, the region’s expanding populations are sure to need more electricity as economies recover. Middle Eastern countries will add thousands of megawatts of new solar-power capacity through at least 2025, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Saudi Arabia, which currently has about 500 megawatts of renewables capacity, targets a 120-fold surge to 60 gigawatts by 2030, with most of it in solar. That’s a lofty goal, and while initial progress has been slow, the Energy Ministry is taking concrete steps: it aims later this year to select winners in the country’s second tender round of solar projects, and in April it began seeking bids for a third round.

In the United Arab Emirates, Abu Dhabi said last week that it received a record-low bid for the installation of a 2-gigawatt plant. That project, to start operating next year, would more than double Abu Dhabi’s solar capacity. A day later, the neighboring emirate of Dubai awarded a contract for a project to generate power at a historically low price --part of a solar park designed to produce 5 gigawatts by 2030.

Qatar chose partners earlier this year to build its first solar plant, and in March private partners completed financing arrangements for the largest project in Oman, the biggest Middle Eastern oil producer outside of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Private power developers, who can tap international funds at low interest rates, are helping to cut financing costs and lead to even cheaper power, said Mills of Qamar Energy. Continued expansion of solar power in the region “comes down to financing and power-demand growth,” he said.

— With assistance by Will Mathis

6 May 2020

Bloomberg Green