Killer heat: how a warming land is changing Australia forever.

The frontline -> Inside Australia's climate emergency: the killer heat

Australia is heating faster than the global average, and extreme heat days are on the rise. Doctors say there’s clear evidence that it’s killing people prematurely

This feature is best experienced with sound. Turn audio on here.

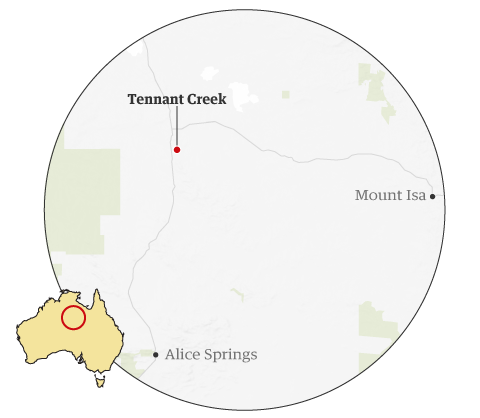

Patricia and Norman Frank say extreme heat is changing the daily lives of people who have lived on the land for generations. The siblings are traditional owners from Tennant Creek in the heart of the Northern Territory outback.

The region around Tennant Creek is one of the hottest parts of Australia.

On the day the Guardian visited, it was 41C — but that’s mild compared to the hottest day last year, which was four degrees higher. The average maximum temperature last year was 33.9C, up nearly a degree since 1970.

Patricia says it’s now too hot for kids to play in the daytime. Instead, they wait until night to walk the streets.

Plants that were traditionally used for food either no longer grow, or grow poorly. “Animals are hibernating and aren’t coming out in the right season,” she says.

People used to live in tin sheds all year round, says Norman, but that is no longer possible.

“Today you go underneath a tin shed, you’ll be fried.”

Australia is heating faster than the global average. Across the continent and throughout the year, it is 1.4C warmer than it was early last century. But that figure alone can be misleading.

As temperatures increase due to escalating greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, maximum temperatures rise even more sharply.

Scientists warn the greatest threat is an escalation in heatwaves. These can be driven by both human carbon dioxide emissions and natural phenomena, but the evidence that they are increasing due to the former is clear.

Extreme heat has caused more deaths in Australia than all other natural disasters put together

This chart shows the number of deaths in the period 1900 t0 2011 for all ‘natural hazards’ listed in the PerilAUS database. Extreme heat has been responsible for 55% of all listed natural hazard fatalities

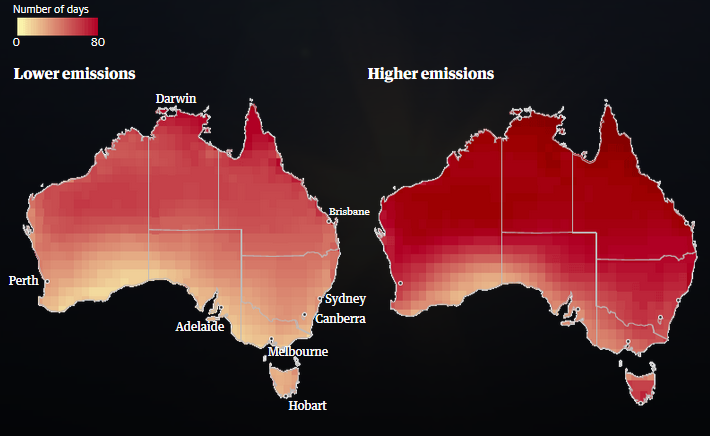

Heatwaves are projected to increase in Australia

These maps show the projected increase in heatwave days by the period 2081-2100 when compared to the historical average. The first map shows a scenario in which emissions start declining in about 2040 (RCP 4.5), and the second shows a scenario in which emissions continue to rise (RCP 8.5). A heatwave is defined as three consecutive days above a certain threshold for that location

Australia’s seven hottest days on record were in the second half of December, 2019. Prior to 2018, there were only four days on which the maximum temperatures across the country were on average hotter than 40C. In the past two years there have been 18.

Karl Braganza, the Bureau of Meteorology's manager of climate monitoring, says the number of extreme heat days — those hotter than 35C — has increased five-fold in just the past 30 years.

That trend was predicted and is projected to continue.

“Some of the extreme temperatures we are seeing will be closer to the average by the mid-21st century, which isn’t that far away,” Braganza says.

The health effects of this will be profound, says Dr Diana Egerton-Warburton, an emergency doctor at Monash Health in Melbourne.

Extreme heat strikes the body at a cellular level, breaking down fats and protein. “That’s really scary because it can have effects right from the brain to the heart to the kidneys,” Egerton-Warburton says.

It leads to more heart attacks, strokes, mental health problems and increased risk of injury: “There is clear evidence that it is killing people prematurely”.

The mortality rate increases nearly 20% when the average temperature across a 24 hour period is above 30C, she says. “When the overnight minimum is 24C or above is really when our heat health alert steps in.”

In early 2009, two weeks before the Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria that killed 173 people, Egerton-Warburton was working in the Monash medical centre emergency department in Melbourne when an extreme heatwave struck.

Temperatures in the state got as hot as 48.8C. More than 400 people died over four days in south-eastern Australia due to heat exposure.

In Tennant Creek last year, there were 113 nights during which the temperature stayed above 24C, the level at which health concerns are raised.

The town is on Warumungu land; more than 50% of the population is Indigenous. Norman and Patricia say their people have been left feeling helpless as rising heat has broken a connection with the land that stretches back millennia.

“One old fella from Utopia came and visited me three or four weeks ago,” Norman says.

“He said: ‘you know what, my country’s dry, your country’s dry ... It’s probably the climate change’.”

“Our ancestors and our fathers left our country there for us,” he says. “If we want to make a change we need a better way of living. A better way of living for our kids and our future.”

The Guardian