How Timbuktu’s Ancient Manuscripts Impact Africa’s Climate Map

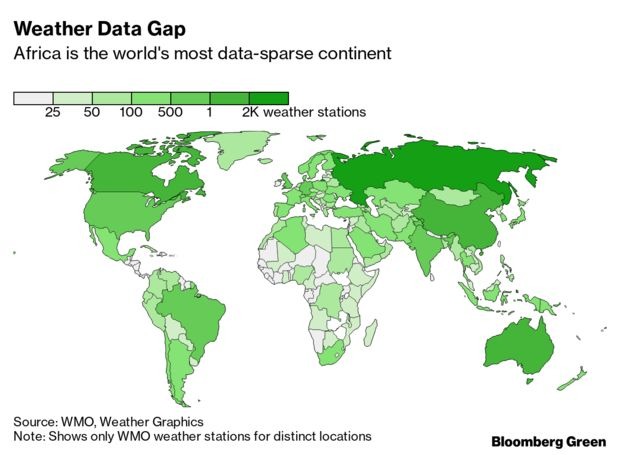

When it comes to climate, Africa is the world’s most data-sparse continent, setting the region back in global negotiations. New weather stations and preserving old books will play a critical role.

By August 4, 2021, 7:01 AM GMT+3 Weather station 61223 had been faithfully recording data on the temperature, wind and rainfall in the legendary city of Timbuktu for 115 years before March 30, 2012.

On that day, the station, a discreet concrete building by the airport, reported a maximum temperature of 105º Fahrenheit. Then, it went silent. On April 1, rebel Tuareg fighters under the multi-colored banners of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad surrounded and captured the area. Later, the jihadists of Ansar Dine followed, waving their black flag with the shahada—the Muslim declaration of faith—emblazoned in white. Soon, Sharia law was implemented across the city.

Moussa Touré watched the events unfold from Mali’s capital of Bamako with horror, and a sense of relief. As director of the African country’s weather observations network, he was responsible for the meteorologists stationed across the country and, luckily, he’d managed to evacuate all the National Meteorological Agency’s employees from Northern Mali in time. That included the three people in charge of Station 61223, one of only three facilities in Mali that had collected weather data without interruption for more than 100 years. Their safety had come at a cost. “It was the only station in the region, the one that allowed us to understand extreme weather events in northern Mali,” Touré says, a shade of sadness in his voice. “We knew leaving our personnel there without any protection would mean putting them at risk.”

One weather station going dark was nothing compared to the chaos that ensued. The fall of Muammar al Qaddafi’s regime in Libya in 2011 had brought hundreds of fighters back to Mali and Niger. By 2012, myriad insurgent groups were causing destruction in the Sahel, a predominantly desert region stretching across Africa from Mauritania and Mali to the west, all the way to Sudan and Eritrea to the east. Islamist groups linked to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State took hold of several territories. A United Nations peacekeeping mission and a separate French-led counter-terrorism operation were deployed. Almost a decade later, the region is still unstable. Mali has suffered two coups d’état in less than a year. In July, Assimi Goita, who took power after leading the latest uprising, survived an assassination attempt.

But the loss of Station 61223 was keenly felt by the community of scientists trying to better understand the impact of global warming on the Earth’s climate—especially in Africa, where weather phenomena are chronically understudied. The complex mathematical models climate scientists depend on are fed with millions of data points from thousands of stations scattered across the planet—from the dunes of the Sahara desert to the busy streets of Beijing. Measurements of temperature, rainfall, humidity, solar radiation, as well as wind intensity and direction, allow scientists to test the accuracy of their models. The closer their forecasts hew to changes on the ground, the more confidence researchers have in their ability to make predictions.

“Weather and climate have a huge variability, so you need observations over decades and even over centuries,” says Peer Hechler, a scientific officer at the World Meteorological Organization, the United Nations agency that oversees weather and climate issues. “If you have data-sparse areas, you have a problem understanding the weather and the climate globally.”

That’s one of Africa’s biggest problems when it comes to tackling climate change, according to the WMO’s inaugural State of the Climate report released last year. The continent has the world’s least developed land-based weather observation network, amounting to only one eighth of the minimum density recommended by the WMO. The issue will be under the spotlight next week as the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change releases the first part of its Sixth Assessment Report, which summarizes scientific discoveries about climate change from the past seven years and will form the basis for further policy discussions, including the UN-sponsored COP26 conference planned for November.

What weather data infrastructure is in Africa is deteriorating fast, with only 22% of stations meeting global reporting standards in 2019.

The lack of data makes it harder to protect people against the impacts of climate change on an especially vulnerable continent. Africa has contributed the least to global warming and is also worst-equipped to deal with the devastating consequences of rising temperatures, according to the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change. A report by the International Monetary Fund estimates gross domestic product per capita in the Sahel would fall around 2% for every 1º Celsius of global temperature rise, compared with a 1% increase in cooler, wealthier countries such as Canada and Russia. For the people of Mali, the consequences of losing Station 61223 were much more immediate—and tragic. The data it gathered was essential for predicting the sudden and violent gusts of wind that sweep over the region, causing sandstorms and dangerous water currents. Residents were well-trained to listen for alerts from Station 61223 warning them of impending gales. The pinasses, long flat canoes that carry people, cattle and goods along the Niger river, would stop their journeys and take refuge.

In 2011, about 10 people died in wind-related incidents around the Niger river and Lake Débo, Mali’s largest lake. That number soared to 70 the year after Station 61223 went offline.

Youba Sokona has been frustrated by the lack of African weather data for almost half a century.

He first encountered the problem when he was working on his PhD at age 28, researching ways to optimize dam construction in the Senegal River basin. “In order to design a dam, you need a long-term series of hydro-meteorological data of a minimum of 100 years,” says Sokona, now 71. “I had only seven years of observation for the entire river system.”

That sort of information is usually readily available for projects in Europe and North America. The discrepancy became more obvious to Sokona as he rose through the ranks of the global climate community. An expert on sustainable development in Africa, he was appointed lead author of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report in 2014. The massive document is published by the UN agency every six to seven years, summarizing the latest scientific discoveries about climate change in order to guide world leaders on how to tackle the crisis.

Speaking from his home in Bamako, where he’s returned after a decades-long career leading climate institutions all over the world, Sokona recalls the fraught politics around the document, which has to be approved by all UN member countries. “Suddenly African members realized that there was lots of information on climate change in the Northern Hemisphere, but nothing on the South,” he says. “It wasn’t because climate change didn’t happen in the South, it was because there was no data, no previous research the IPCC could rely on.”

Photographer: Thomas Koehler/Photothek

African representatives threatened to reject the 2014 report, and harsh words were exchanged during meetings in Stockholm and Yokohama, Sokona says. Still, the document was eventually published, laying the groundwork for global leaders to set the target of keeping global warming below 1.5ºC compared to pre-industrial levels that underpins a swathe of climate policies today.

The experience, however, had underscored an uncomfortable inequity. IPCC authors launched a program to get more academics from Africa involved; more than 700 have since attended talks and conferences that highlighted gaps in the IPCC’s African data, Sokona says. They’re encouraged to gather information in their own countries, publish papers, and give feedback on existing publications to bring African issues to the attention of authors in developed nations.

The upcoming IPCC report includes an unprecedented number of African authors and is expected to highlight the lack of data from the continent, according to sources familiar with the document who asked not to be named because its contents are confidential.

But the gap in research between developed and developing countries is still large. “Limited information is one of the main problems,” Sokona says. “We have made a huge progress and impact in Africa since the Fifth Assessment, but a lot more is still needed.”

Still, no one in the Sahel needs a scientist to tell them that the climate is changing in dangerous ways.

Those who live there have watched over the past few decades as rivers dried up, rain became less predictable, and deadly droughts and extreme heat became more common. The harsh weather has made it more difficult to grow crops such as rice and cotton, both major economic drivers. That’s forced hundreds of thousands of people to move to the capital Bamako to find work, or to take their chances embarking on dangerous migration routes along the Sahara to try and reach Europe.

There was a time, prior to the events in 2012, when Mali’s then-president Amadou Toumani Touré kept a close eye on the weather. “He followed all weather forecasts on TV and he would call the minister for the weather to ask about specific information,” says Touré, the meteorological agency director. (The two aren’t related.) Touré the former president was overthrown by a coup in 2012.

Since then, climate change has risen to the top of the political agenda in many Western countries as citizens demand stronger action. But in Africa, there are often more pressing matters. With national meteorological agencies running on stretched budgets and political leaders uninterested in funding climate research, African researchers rely on support from international institutions or nonprofit organizations. The World Bank, International Monetary Fund and dozens of nonprofits have initiatives to expand the continent’s network of weather stations. But as soon as a program ends, so does its budget. The facilities fall into disrepair, and the data stops coming in.

“It turns out there’s quite a long road between a good idea and having something in the field that actually works,” says Nick van de Giesen, a professor at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. He’s spent the last seven years running the Trans-African Hydro-Meteorological Observatory, or TAHMO, a network of weather stations scattered across Africa that provides data to about 300 scientific organizations, including the WMO.

The most common type of facility is known as a synoptic weather station—that’s what Timbuktu’s Station 61223 was. They’re usually manually operated and include delicate equipment used to measure everything from soil moisture to barometric pressure. A team of operators is needed to digitize data and maintain the instruments. In the African countryside, that means a constant fight against insects and animals.

“Insects love to get into weather stations because they’re usually cooler than the outside,” Van de Giesen says. “We’ve found nests of wasps, ants, birds, anything you can think of.”

Source: TAHMO

When he launched TAHMO, Van de Giesen’s vision was to make weather stations more affordable. The goal was to cut the cost of establishing one from $20,000 to just $200. To cut maintenance costs, the group designed a compact station with no moving parts that transmits data automatically through a cell phone. The whole process is so simple, it can be maintained by a child. In fact, one of the nonprofit’s initiatives installs stations in local schools as part of an effort to educate young people on the importance of weather stations.

Van de Giesen hasn’t quite reached his target of $200 per station, but the current cost of about $2,000 per unit makes TAHMO’s much more affordable than other alternatives.

The group is proceeding with caution. Their priority, Van de Giesen says, is to install only what they can actually maintain. Of the more than 600 TAHMO weather stations in Africa, none are in Mali.

Stories from Timbuktu, the ancient center of learning and trade in the southernmost corner of the Sahara, have captured Hienin Ali Diakité’s imagination since he was a child. His father, a Malian migrant in Burkina Faso, would spend hours recounting his own long journeys across the desert and the Niger river, waxing lyrical about the city’s golden ages.

Timbuktu was a central node in the region, luring visitors from all over. In the 16th century people travelled for weeks and months to learn Islamic theology, history, and philosophy from the wise sages who lived there. Bedouin tribes that cruised the desert passed through as they led caravans of camels carrying salt, gold and slaves across the desert.

Photographer: Souleymage Ag Anara/AFP

All of them brought new knowledge, from treatises of medicine, astronomy, and Islamic law to poetry, popular culture, agriculture techniques, and—crucially—updates on the weather. The information was recorded in manuscripts written mostly in Arabic, but also in local languages such as Songhay and Tamasheq. The sheets passed within families from one generation to another, hidden away in the city’s signature mud mosques and houses.

By the 19th century, the fall of the Malian empire and colonization by the French brought an end to the centuries-old practice of studying the manuscripts. The documents faded away, forgotten by almost everyone. When western scholars found them more than a century later, they were baffled. Their findings allowed them to rewrite West African history, which they previously thought had been preserved solely through the oral tradition. Diakité’s obsession with Timbuktu’s rare manuscripts prompted him in February 2012 to travel to the city’s Ahmed Baba Institute, which was working on digitizing about 20,000 of the ancient documents. Diakité didn’t know it at the time, but he was one of the last researchers from outside of Timbuktu to see the manuscripts in person before insurgents took over the city. Back home in France, he watched on television as the city was taken over. He followed the story from the victory of the Islamist radicals to the destruction of religious mausoleums, the devastating news of manuscripts burned by terrorist groups—and, later, the reports that Timbuktu’s longtime custodians had saved many of the manuscripts, either by hiding them in the city or by smuggling them to Bamako.

Now a cataloguer of West African manuscripts at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library at Saint John’s University in Collegeville, Minn., Diakité spends his days scanning and analyzing a trove of somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 manuscripts. They’re just a small part of what are thought to number in the hundreds of thousands total.

The texts, some of which can be accessed online, give hints of what the weather was like centuries ago. One talks about a drought-led famine in 1785; others include passages on the precise places where rivers sprung up in the desert during the rainy season. The large number of magic intonations said to invoke rain, or to make it stop, indicate that the weather was something people spent a lot of time trying to control.

In Europe, researchers have used manuscripts and old books from monasteries and libraries to understand what the climate was once like, but no one seems to have done the same with the Timbuktu manuscripts until now. “The first thing is to preserve everything, and the second thing is to make sure you can see these manuscripts from anywhere,” Diakité says. “We’re going well, but there’s still a lot we need to work on.”

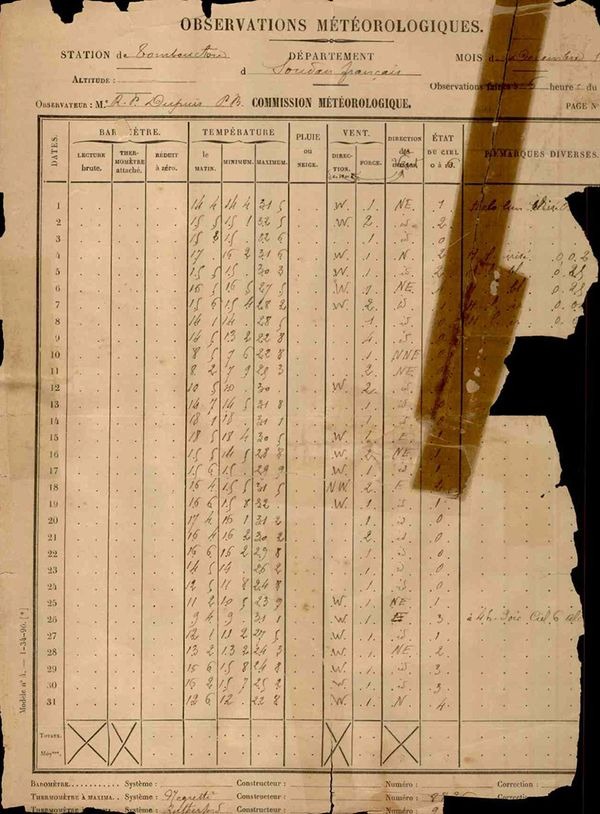

Diakité’s effort to save that valuable information echoes a larger push to recover lost African weather data. Hundreds of books and files of valuable weather readings are sitting in archives across the continent, many covered in mold, others left at the mercy of termites, fires and floods.

“We have a wealth of information still on paper in Africa, in the meteorological services and in other institutions that measured and observed weather and the climate in the past,” says Hechler, from the WMO. “We need to hurry up to locate this data on paper, scan it, make inventories and code the data—it’s a huge effort that needs a lot of people.”

The WMO has sponsored data-rescue programs and worked to attract donors. From 2014 to 2016 the organization partnered with state meteorological offices in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger on a large-scale weather data rescue operation. Thousands of documents that had been piled up haphazardly in storage rooms are now kept in neatly-aligned boxes, all properly coded and classified.

Source: Mali Meteorological Agency

Source: Hill Museum & Manuscript Library

In Mali, 14,655 monthly climatological tables have been scanned and linked them to the national database. The information allowed agency experts to develop models for the beginning and the end of the rainy season in different regions in the country.

As for Station 61223, it remains offline because the meteorological agency still can’t guarantee the safety of employees and installations, says Touré. About 90% of its instruments will need to be replaced if it ever resumes its work. Still, Touré’s agency has managed to install 40 new weather stations in Mali over the past decade.

“There’s sort of a skeleton of data in Africa now,” Hechler says. “With all these initiatives we can connect the new data we’re gathering today and in the future with existing data. It’s the second-best way to do things, but it’s still a good way scientifically.”

With assistance by Katarina Hoije

August 2021

Bloomberg