How Has COVID Changed Fridays for Future?

When Fridays for Future (FFF) takes to the streets on March 19, activists around the world are going to be doing everything they can to make sure the climate crisis stays in the news.

In the Netherlands, 16-year-old Erik Christiansson will join a small physically distanced protest in The Hague with other Dutch FFF members.

Meanwhile, some 12,000 kilometers to the south in Zambia, a 26-year-old man named Chilekwa Kangwa will give a radio interview highlighting the importance of education and sustainable agriculture.

Across the Atlantic and eight time zones away, Adriana Calderon, an 18-year-old Mexican, will be deploying a sticker campaign in support of renewable energy and targeting the massive global K-pop fan base on social media, in the hope that the FFF message goes viral.

"The big marches with tens of thousands of people which we had in 2019 are just not possible anymore," said Christiansson, 16, speaking with DW from his home near Utrecht.

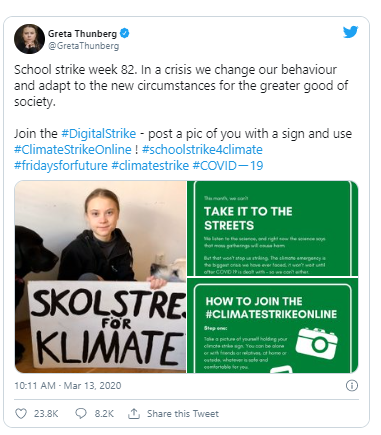

Over the past year, he and other young activists around the globe have tried to adapt and come up with new virtual approaches to get the message out — a #DigitalStrike from online class, for example, or social media posts with eye-catching slogans.

Overall, though, it's been a struggle. "We noticed that it's been a lot less effective," said Christiansson, who has been involved with climate advocacy for about two years. "On social media, often your posts get seen by other people who already agree with you and you don't really get that much attention from outside."

Calderon has also found it difficult to share her climate concerns under Mexico's emergency coronavirus measures. Speaking with passersby at an in-person march, she said, you may have several minutes to get your message across. Online, that attention span shrinks to just seconds.

"With social media, it's very hard — you have to be really precise in your words," she said. Her local FFF group, based in Cuernavaca, Morelos, found it too difficult to carry on under the quarantine measures and shut down its social media presence in November.

Has the Pandemic Weakened Friday's for Future?

Still, Friday's for Future has managed to continue. But can it regain the momentum it once had?

"Visible public events are undeniably the foundation for a social movement — to mobilize people, to mobilize support and to gain public attention. And this is definitely missing," said Jens Marquardt, a postdoctoral researcher in climate change politics and societal transformation at Stockholm University.

While it was inevitable that some media coverage would drop off in 2020 once the movement's novelty had worn off, he believes the pandemic has hit FFF particularly hard and made it difficult for the movement to get its message out. But that hasn't necessarily been detrimental, said Darrick Evensen, a professor of environmental politics at the University of Edinburgh.

"It's a very different world because of the coronavirus pandemic and the manifestation of climate activism has certainly evolved — necessarily so because of the lack of opportunities for in-person interaction," he said.

Christiansson agrees. Stuck at home in the Netherlands under lockdown, Christiansson helped produce some webinars for the FFF YouTube channel and began chatting with other activists his age abroad.

"We've talked a lot more internationally than we did before, when everyone was focused on their own strikes and their national politics," he said. "Since we were communicating with everyone online already, it was easy to get connections with people in other countries as well."

Evensen points out that it's not just the medium of the message that's changing, either — the message itself has evolved over the last year. Global strikes like the one set for this Friday aren't just stressing the climate emergency; talking points now include worker welfare, climate justice and the role of civil society in climate decision-making.

"The rhetoric is changing," said Evensen. "It does seem that this really heavy focus on science is waning, and it's become more of a blended image in terms of the interests that are that are being represented."

This shift in focus could be linked to the secondary effects of the pandemic and a heightened perception of risk, both in terms of our health and the health of the planet, he said, adding, "People are maybe spending more time outside, people are thinking more about their interaction with the natural world."

Evensen was part of a recent UK study showing that climate concerns haven't diminished during the pandemic, as they did during the last global financial crisis in 2008 — and he said he was seeing similar data in other parts of the world. In some cases, respondents even identified climate change as a bigger threat than the virus.

"It is actually quite astonishing to see that this [FFF] movement has been so resilient and robust, despite this massive crisis," said Marquardt. "This year of reflection has been helpful in shaping the agenda about what this movement is about and what this movement wants to achieve in the future."

More Space for Marginalized Voices

Marquardt said the pandemic has also given FFF the chance to bring in marginalized voices. At the last global strike on September 25 the movement emphasized the "most affected people and areas," or MAPA, a new term for the areas of the world that will be disproportionately harmed by climate change, in an attempt to bring them into the global debate.

"Of course, you still have some imbalance, in terms of basic internet access, ways of communicating, who speaks for whom. [But] the pandemic has very much increased cooperation and also exchange between different national and local activist groups," he said.

Adriana Calderon, who joined FFF in Mexico about a year ago just as the world was shutting down, has thrown herself into virtual campaigns on social media and YouTube, coordinating global support for MAPA. Before the pandemic, she said, people in the Global South lacked this dedicated community to express themselves among people who understood their concerns.

"Today, there are more than a hundred activists, and we are like a community. We have calls on Saturdays, we have our own social media. We plan together what we want to do, and we ally with other groups to make campaigns," she said. "There was a community before, but now I think the international community is doing more because we were forced to move to digital, forced to interact with other groups. And I can see how much the movement has grown since last year."

'We Can't Stop Here'

Taking part of that growth has been Chilekwa Kangwa, a 26-year-old from Mpika in northeastern Zambia. Kangwa, who founded the Action for Nature conservation and development group in 2017, only got involved with FFF recently. But he has already linked up with several campaigners in other countries to swap stories about sustainable agriculture and other issues relevant for his region.

"Climate change affects people in different ways," he said, adding that this global exchange through MAPA can help his community, and others, find the tools needed to fight climate change and transform livelihoods. "What should be done now is that we must begin to listen to one another."

On Friday, Zambia's less restrictive coronavirus measures will allow Kangwa to take part in a march in Mpika with many excited young students, the first such FFF event in his community. That's an experience that Calderon hopes will soon be possible in her part of the world, too.

"People miss physically going on strike," she said. But she thinks that when the world begins to emerge from the COVID restrictions, the digital advances of the last year won't be forgotten. "At the end of the day, we will still be using both. We have developed so much, and we can't stop here."

18 March 2021

EcoWatch