In best-case reforestation scenario, trees could remove most of the carbon humans have added to the atmosphere.

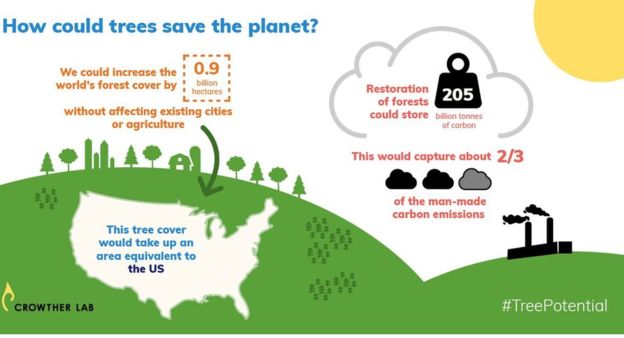

A study finds that close to a trillion trees could potentially be planted on Earth—enough to sequester more than 200 billion tons of carbon. But environmental change on this scale is no easy task.

If a tree falls in the forest, but someone sticks around to replant it, does it still make an impact in the fight against climate change?

The answer, it seems, is yes. And, according to new research published today in the journal Science, that’s exactly the tack we humans should take. The study, which presents a global map of degraded lands that could naturally support new trees, suggests that the best case scenario for forest restoration would remove more than 200 billion tons of carbon from the atmosphere—enough to single-handedly offset two decades worth of global emissions produced at the current rate.

That kind of change doesn’t come easy, or fast. The researchers’ proposal, which calls for the seeding of approximately 1 trillion trees, is ambitious to say the least. And when it comes to rejiggering the ecological landscape on such a grand scale, there’s a whole range of social, political, and economic considerations to take into account.

“This is a very rigorous and timely approach...that highlights where [forest] restoration can and should be happening,” says Robin Chazdon, a forest ecologist at the University of Connecticut who authored a commentary on the study. But, she adds, while “it’s good and important to know the potential...we have to [do the work to] make the potential the reality.”

If enacted, though, global attempts at reforestation might constitute one of the most powerful strategies available to combat the climate crisis, the researchers say. Real-world obstacles aside, fully implementing this initiative could dwarf the projected impacts of other mitigation methods, like shifting a good chunk of our energy needs to wind power, which, in plausible scenarios, would only account for about 20 billion tons of atmospheric carbon.

The new study builds on a long line of research championing the transformative powers of forest restoration, which capitalizes on one of the biggest perks of greenspace: Due to photosynthesis, plants are living sponges for carbon, which they can guzzle from the air and store over the long term. But this paper is the first to put hard numbers to the world’s arboreal carrying capacity, the number of trees the Earth can sustainably support.

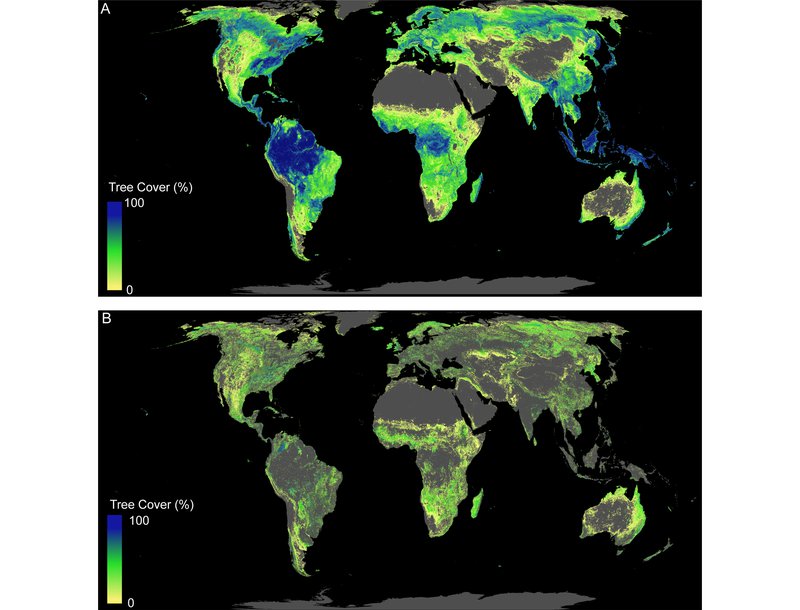

Using a global dataset of ground-based measurements and satellite images, a team of researchers led by Jean-Francois Bastin and Thomas Crowther of ETH-Zürich sussed out the environmental conditions most conducive to tree growth in protected forest areas around the world. They then used these criteria, which factored in things like soil quality and climate, to scour the rest of the planet for regions where saplings might have a shot at taking root.

The numbers were staggering. While more than 21 billion acres around the world—roughly two-thirds of Earth’s land—could naturally harbor forest (as opposed to other kinds of natural ecosystems, like grasslands), less than 65 percent of that space actually does. By the study’s calculations, that leaves almost 8 billion acres for possible planting. At roughly 160 trees per acre, that’s about 1.3 trillion trees that could exist, but don’t.

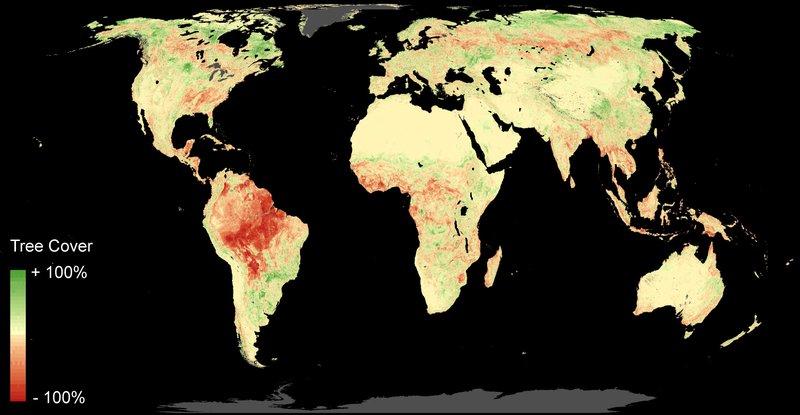

Not all 8 billion acres the researchers identified are readily available, however, as nearly half of them are taken up by cropland or urban area. The remainder exists in the form of degraded land, where human activity has reduced a habitat’s ecological productivity. In other words, places that would naturally support forests if given the chance. It’s here that the researchers found the potential for approximately 700 billion new trees, which, once fully grown, could collectively sequester 225 billion tons of carbon.

According to the study, these arboreal additions would gobble up around two-thirds of the 300 billion tons of carbon currently bopping around the atmosphere as a result of human activity, reducing the global burden to levels we haven’t seen since the mid-1900s. Waking up to that reality tomorrow would be like rewinding the climate clock by nearly a century.

“We were absolutely amazed as the results came out,” Crowther says. “It genuinely blew my mind.”

There are a few caveats, though. One of the biggest is timing: Mature, carbon-hungry trees don’t spring up overnight. “These projections kind of assume that, from day one, the forest is back,” Chazdon says. “But the process of reforestation takes several decades, even in ideal conditions.”

Given the accelerating pace of climate change, the long lag in payout is even more reason to act fast, Bastin says. If humankind doesn’t deviate from its current emissions trajectory, nearly a quarter of the land available for restoration will be gone by 2050. “The race [against climate change] is one I’m not sure we’re going to win,” he says. “The sooner [reforestation] happens, the better.”

The process also wouldn’t come cheap. At roughly 30 cents a sapling, planting the trees themselves is actually a good deal, Bastin says. But there are other costs to consider, including those incurred by labor, logistics, and maintenance of burgeoning forests. And the amount of planning and foresight required for forest restoration can’t be overstated. Not all trees are created equal, and planting species that are invasive, or ill-suited for a particular habitat could backfire, in some cases even hastening furtherdegradation, Chazdon says.

Additionally, before trees could be planted in most parts of the world, environmental researchers would need to determine the cultural and economic impacts of reforestation, says Salima Mahamoudou, a research associate with the World Resources Institute who was not involved in the study. She points out that collaborations should include experts in other fields, as well as those living in and around the team’s targeted regions. “Forest restoration is a people issue, just like climate change is a people issue,” she says. “We need to start involving the people who will be impacted.”

An interdisciplinary approach would be especially useful for navigating issues of land ownership and land-use planning, says Daniela Miteva, an environmental economist at Ohio State University who was not involved in the study. Just because a forest can be restored somewhere, doesn’t mean it should, she says, especially if it might better serve the local community as a lucrative space for agriculture, for instance. And in many of the areas where reforestation could occur, farmers aren’t well compensated for giving up land or changing their practices.

But replenishing the world’s forests isn’t an all or nothing solution: Even shy of a trillion trees, every sapling planted makes a difference.

Such efforts are already well underway, Crowther points out, highlighting the effort of the Trillion Trees Campaign, aptly named for its goal of planting a trillion trees worldwide. (As of this writing, the organization is at 13.6 billion.)

Additionally, 59 countries, states, and organizations are currently pledged to the Bonn Challenge, a United Nations-endorsed initiative working to restore 850 million acres of deforested and degraded land by 2030. Among them are the United States and Brazil, which, according to the new study, are two of the six countries with the most restoration potential (the other four being Russia, Canada, Australia, and China). Even though the tropics remain the region where reforestation would probably still get youthe biggest bang for your bark in terms of decarbonizing the atmosphere, Bastin says, the study suggests that a wide range of countries could have a role to play in the years to come.

Miteva stresses that, as powerful as reforestation could be, it’s no silver bullet—and we’ll need all the help we can get from other, more immediate mitigation tactics. Part of that includes safeguarding the vegetation we already have, which currently have500 billion tons of carbon under lock and key. In this neck of the woods, Miteva says, “you don’t have to wait for the trees to grow.”

But excluding the promise of reforestation would be, in a sense, missing the forest for the trees. After all, living, growing forests are the climate gift that keeps on giving. Once mature, an acre of trees could soak up more than two tons of carbon per year—and that adds up fast, Crowther says.

And trees, of course, are good for more than storing carbon. In many parts of the world, careful and conscientious reforestation could have ripple effects on everything from ecosystem biodiversity to food and water security, replenishing local resources and boosting economic profits.

“I don’t want climate change solutions to be a burden on us all,” Crowther says. “We need to find positive solutions...and this is a nice, simple, and enjoyable one that can have a meaningful, tangible impact on us all.”

And there’s enough room, Swiss scientists say. Even with existing cities and farmland, there’s enough space for new trees to cover 3.5 million square miles (9 million square kilometers), they reported in Thursday’s journal Science . That area is roughly the size of the United States.

The study calculated that over the decades, those new trees could suck up nearly 830 billion tons (750 billion metric tons) of heat-trapping carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. That’s about as much carbon pollution as humans have spewed in the past 25 years.

Much of that benefit will come quickly because trees remove more carbon from the air when they are younger, the study authors said. The potential for removing the most carbon is in the tropics.

“This is by far — by thousands of times — the cheapest climate change solution” and the most effective, said study co-author Thomas Crowther, a climate change ecologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

Six nations with the most room for new trees are Russia, the United States, Canada, Australia, Brazil and China.

Before his research, Crowther figured that there were other more effective ways to fight climate change besides cutting emissions, such as people switching from meat-eating to vegetarianism. But, he said, tree planting is far more effective because trees take so much carbon dioxide out of the air.

Thomas Lovejoy, a George Mason University conservation biologist who wasn’t part of the study, called it “a good news story” because planting trees would also help stem the loss of biodiversity.

Planting trees is not a substitute for weaning the world off burning oil, coal and gas, the chief cause of global warming, Crowther emphasized.

“None of this works without emissions cuts,” he said.

Nor is it easy or realistic to think the world will suddenly go on a tree-planting binge, although many groups have started , Crowther said.

“It’s certainly a monumental challenge, which is exactly the scale of the problem of climate change,” he said.

As Earth warms, and especially as the tropics dry, tree cover is being lost, he noted.

The researchers used Google Earth to see what areas could support more trees, while leaving room for people and crops. Lead author Jean-Francois Bastin estimated there’s space for at least 1 trillion more trees, but it could be 1.5 trillion.

That’s on top of the 3 trillion trees that now are on Earth, according to earlier Crowther research.

The study’s calculations make sense, said Stanford University environmental scientist Chris Field, who wasn’t part of the study.

“But the question of whether it is actually feasible to restore this much forest is much more difficult,” Field said in an email.

The study shows that the space available for trees is far greater than previously thought, and would reduce CO2 in the atmosphere by 25%.

The authors say that this is the most effective climate change solution available to the world right now.

But other researchers say the new study is "too good to be true".

The ability of trees to soak up carbon dioxide has long made them a valuable weapon in the fight against rising temperatures.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said that if the world wanted to limit the rise to 1.5C by 2050, an extra 1bn hectares (2.4bn acres) of trees would be needed.

The problem has been that accurate estimates of just how many trees the world can support have been hard to come by.

This new report aims to show not just how many trees can be grown, but where they could be planted and how much of an impact they would have on carbon emissions.

The scientists from ETH-Zurich in Switzerland used a method called photo-interpretation to examine a global dataset of observations covering 78,000 forests.

Using the mapping software of the Google Earth engine they were able to develop a predictive model to map the global potential for tree cover.

They found that excluding existing trees, farmland and urban areas, the world could support an extra 0.9bn hectares (2.22bn acres) of tree cover.

Once these trees matured they could pull down around 200 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide, some two-thirds of extra carbon from human activities put into the atmosphere since the industrial revolution.

This is a quarter of the overall amount of CO2 in the air.

"Our study shows clearly that forest restoration is the best climate change solution available today and it provides hard evidence to justify investment," said Prof Tom Crowther, the senior author on the study.

"If we act now, this could cut carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by up to 25%, to levels last seen almost a century ago."

The researchers identify six countries where the bulk of the forest restoration could occur: Russia (151m hectares), US (103m), Canada (78m), Australia (58m), Brazil (50m) and China (40m).

But they say speed is of the essence because as the world continues to warm then the potential area for planting trees in the tropics would be reduced.

"It will take decades for new forests to mature and achieve this potential," said Prof Crowther.

"It is vitally important that we protect the forests that exist today, pursue other climate solutions, and continue to phase out fossil fuels from our economies."

The new study has been welcomed by Christiana Figueres, former UN climate chief, who was instrumental in delivering the Paris climate agreement in 2015.

"Finally an authoritative assessment of how much land we can and should cover with trees without impinging on food production or living areas," she said in a statement.

"A hugely important blueprint for governments and private sector."

What do the critics say?

However not everyone was as effusive about the new study.

Several researchers expressed reservations, taking issue with the idea that planting trees was the best climate solution available to the world right now.

"Restoration of trees may be 'among the most effective strategies', but it is very far indeed from 'the best climate change solution available,' and a long way behind reducing fossil fuel emissions to net zero," said Prof Myles Allen from the University of Oxford.

Others are critical of the estimates of carbon that could be stored if these trees were planted.

"The estimate that 900 million hectares restoration can store an addition 205 billion tonnes of carbon is too high and not supported by either previous studies or climate models," said Prof Simon Lewis from University College London.

"Planting trees to soak up two-thirds of the entire anthropogenic carbon burden to date sounds too good to be true. Probably because it is," said Prof Martin Lukac from the University of Reading.

"This far, humans have enhanced forest cover on a large scale only by shrinking their population size (Russia), increasing productivity of industrial agriculture (the West) or by direct order of an autocratic government (China). None of these activities look remotely feasible or sustainable at global scale."

15 July 2019

*Compilation

BBC, NOVA, AP NEWS