You Can’t Beat Climate Change Without Tackling Disinformation

Over more than a century, PR firms built and fine-tuned a machine to deceive the public.

This column is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration cofounded by Columbia Journalism Review and The Nation to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

In the past month or so, climate disinformation has been making its way into the news more than usual. There was the House Oversight Committee’s climate disinformation hearing in October, and then, just days later, leaked documents from Facebook revealed its role in spreading climate denial. The Oversight Committee’s investigation continues, as does the work to fully understand social media’s role in disinformation, about climate and otherwise.

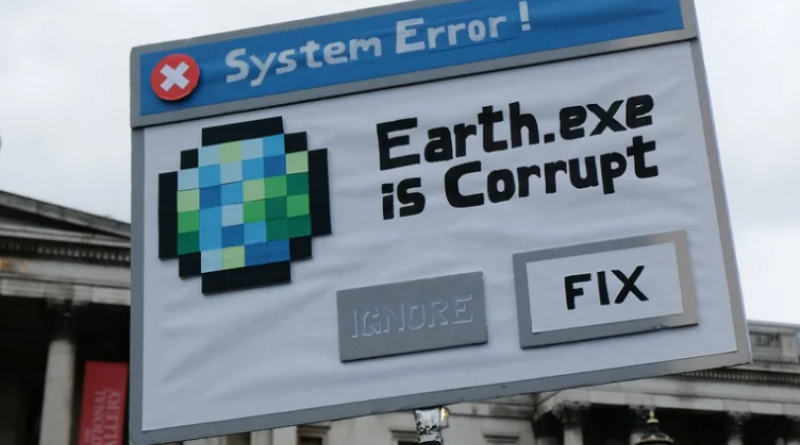

But for all we know about disinformation and how dangerously effective it can be, tackling the problem rarely makes its way into conversations focused on climate solutions. This raises the question: How are you going to implement new green technology or policies without eliminating the obstacle that’s helped block both for decades?

Last week at COP26 in Glasgow, a group of organizers, brands, and advertisers published an open letter calling for disinfo to be on the negotiators’ agenda. Signatories included climate leaders like May Boeve, the executive director of 350.org, and Laurence Tubiana, the CEO of European Climate Foundation; NGOs, like Friends of the Earth and WWF; and brands like Ben & Jerry’s and Virgin Media O2. They had straightforward asks: an agreed-upon definition of climate disinformation, action against climate dis/misinformation to be included in the COP26 Negotiated Outcome, and for tech companies to adopt policies that would crack down on the spread of climate disinformation in both content and advertising.

Climate disinfo, unfortunately, did not make its way into the COP26 negotiations. Had the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports included contributions from social scientists on the role of media and information in tackling climate before the conference instead of next year, as they’re scheduled to be, perhaps that would have been different. In the lead-up to the event, though, Google did announce a new policy aimed at addressing this problem. In partnership with the Conscious Advertising Network, the tech giant said that it will now “prohibit ads for, and monetization of, content that contradicts well-established scientific consensus around the existence and causes of climate change.” That policy doesn’t just affect Google advertisers but YouTube creators as well, which is a big deal given that YouTube has been pushing climate disinformation to millions of viewers for years.

But one policy at one tech platform is not a systemic solution. When pressed about potential outcomes of the House climate disinformation investigation, congressional representatives seemed at a loss about what they could even be proposing to grapple with the threat. There’s a lot of talk of fining the oil companies, of Department of Justice investigations, and of providing more fodder for the two dozen or so climate lawsuits currently in state courts, but nothing around changing the system that enables disinformation in the first place—nothing that would stop the next strategy from working or keep the next industry from lying to the American people. Instead, the focus remains on making Big Oil the next Big Tobacco. But after its momentary embarrassment and a few fines, tobacco went on to profit and, perhaps more importantly, to keep deceiving the public about other products. And the oil companies, many of which were codefendants with the tobacco companies, for their role in developing the cigarette filter, watched that and learned. They pivoted almost immediately away from litigating the science. One former Shell employee told writer Nathaniel Rich, for his story “Losing Earth,” that the oil companies “didn’t want to get caught in our lies the same way the tobacco guys did.” So all that supposed accountability for disinformation just resulted in making companies better at spreading it.

To solve the disinformation problem, we have to understand that it, too, is an industry. PR firms, hired to help companies and industries avoid regulation and circumvent democracy, built and fine-tuned the disinformation machine over more than a century. The House Oversight Committee has said it will broaden its investigation of climate disinformation beyond the fossil fuel industry to its enablers—PR firms chief amongst them. The activist campaign Clean Creatives has been pressuring the PR industry to own its role in crafting and spreading disinformation, and to ditch fossil fuel clients altogether. In response to recent criticism of its work with ExxonMobil (after decades spent helping oil companies and their trade groups create and spread both disinformation and greenwashing),

Edelman PR announced it will be undertaking a 60-day review of its client roster.

Some academics and advocates have begun calling for more than public shaming. “I think that their past actions provide justification for holding them to a higher standard than you would normally hold a company,” Stanford University researcher Ben Franta said. “They need to come under some level of special scrutiny, something that goes beyond mere transparency, that goes beyond disclosure. It’s almost like an information receivership.”

We don’t necessarily have a solution to climate disinformation yet. But it’s clear it will not be dismantled by a company policy here and a congressional investigation there. A problem this large and complex requires concerted effort to solve—and we can’t even start until a critical mass of people realize that doing so is critical to the success of any climate solution.

17 November 2021

The Nation