Wind energy can be the puzzle piece that tackles global warming.

It won't be enough on its own, though.

A rapid expansion of wind energy could achieve a reduction in global warming of 0.3ºC to 0.8ºC by the end of the century, according to a new study. While this would have to be complemented with other emission reduction strategies, it could put the world on a closer path to delivering the Paris Agreement on climate change, the researchers said.

The energy sector remains as one of the main drivers of global greenhouse gas emissions. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that CO2 emissions from coal combustion was responsible for over 0.3ºC of the 1ºC increase in global average temperatures since pre-industrial levels – making coal the main source of temperature rise. So if we want to tackle climate change, replacing coal with renewable energy is a great way to start.

Renewable energy, particularly solar and wind, has seen a remarkable increase over recent years. But it’s not enough yet. In absolute terms, fossil fuels are still the main dominant component of energy demand in every area and globally. That’s why the decarbonization of the energy sector remains a major goal in order to meet the Paris Agreement.

With this in mind, researchers at Cornell University wanted to explore what it would mean in terms of temperature increase for wind energy to continue growing. Onshore wind is a proven and mature technology that has gradually become one of the cheapest energy sources of electricity generation, soon followed by offshore wind.

“Early action will reap dividends,” Rebecca Barthelmie, the lead author of the study, said in a statement. “In terms of averting the worst of climate change, our work confirms that accelerating wind-energy technology deployment is a logical and a cost-effective part of the required strategy. Waiting longer will mean more drastic action will be needed.”

The expansion of wind energy

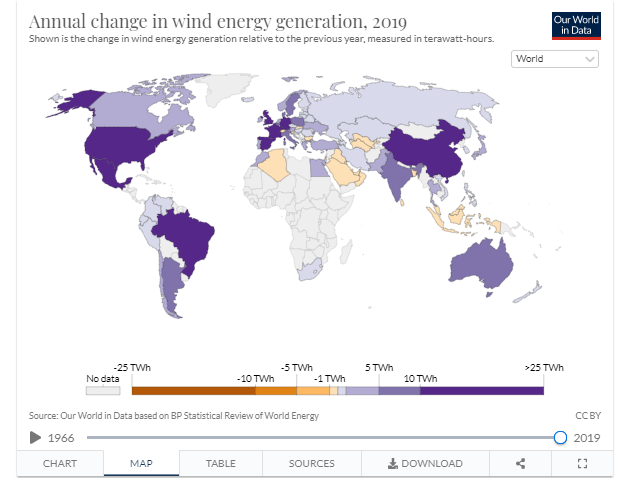

Wind turbines are currently deployed in over 90 countries. The researchers estimate that a total 742 GW of wind energy capacity was installed by 2020, 35 GW of which was offshore. A group of 12 countries has an installed capacity (IC) above 10GW and twenty above 5GW. This is mainly dominated by Asia (mainly China), Europe (mainly Germany), and the US.

Although hydro currently dominates renewable electricity generation (4325 TWh, around 16% of total electricity supply), the largest growth rates and most future scenarios envisage major expansion in the wind and solar energy. Wind energy production has expanded from 104 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2005 to 1273 TWh in 2018.

The recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a leading group of climate experts, suggests that “major reductions” in all sectors are needed to meet the Paris Agreement targets. This is where wind energy enters, capable of driving greenhouse gas emissions down thanks to its fast expansion and lowering costs.

The most aggressive deployment scenarios of wind energy would reduce emissions by around five gigatons by 2030 and by over 10 gigatons by 2050, the researchers estimated. This would reduce global average temperature up to 0.8ºC by the end of the century. Still, this will require a big effort from countries to expand wind energy.

Implementation of the current climate pledges by countries would lead to only a 3.6% annual increase in deployment of wind energy over 2015–2030 compared to the 8.5% per year realized between 2010 and 2016. That’s why several energy agencies have proposed wind energy and electricity generation targets that are more ambitious.

“While the scale of anthropogenic climate change is daunting, our research illustrates that wind energy can substantially reduce emissions of greenhouse gasses at the national and global scale and measurably reduce the amount of temperature increase,” Barthelmie said. “Both technically and economically, advanced deployment scenarios are feasible.”

The study was published in the journal Climate.

24 September 2021

ZME SCIENCE