‘We’re not doomed yet’: climate scientist Michael Mann on our last chance to save human civilisation

The renowned US scientist’s new book examines 4bn years of climate history to conclude we are in a ‘fragile moment’ but there is still time to act

“We haven’t yet exceeded the bounds of viable human civilisation, but we’re getting close,” says Prof Michael Mann. “If we keep going [with carbon emissions], then all bets are off.”

The climate crisis, already bringing devastating extreme weather around the world, has delivered a “fragile moment”, says the eminent climate scientist and communicator in his latest book, titled Our Fragile Moment. Taming the climate crisis still remains possible, but faces huge political obstacles, he says.

Mann, at the University of Pennsylvania in the US, has been among the most high-profile climate scientists since publishing the famous hockey stick chart in 1999, showing how global temperatures rocketed over the last century.

To understand our predicament today, Mann has trawled back through the Earth’s climate history in order to see our potential futures more clearly. “We’ve got 4 bn years to learn from,” he told the Guardian in an interview.

“We see examples of two duelling qualities, fragility and resilience. On the one hand, you find stabilising mechanisms that exist in the Earth’s climate, when life itself has helped keep the planet within bounds that are tailored to life.” For example, the sun’s brightness has increased by 30% since life began on Earth, but life has maintained suitable temperatures.

“But there are examples where the Earth system did just the opposite, where it spun out of control, and did so because of life itself,” Mann says. The great oxidation event 2.7bn years ago saw primitive bacteria start producing oxygen which led to the destruction of the potent greenhouse gas methane in the atmosphere. “That plunged us into a snowball Earth that nearly killed off all of life.

“When we look to all these past episodes, we come away with a sense that we’re not doomed yet – we have not yet ensured our extinction,” he says. “But if we continue on a fossil fuel-dependent pathway, we will leave that safe range we see in the evidence from past Earth history. That’s what makes this such a fragile moment – we’re at the precipice.”

One motivation for the book, Mann says, is the rise of climate doomism: “We haven’t seen an end to climate denial, but it’s just not plausible any more because people can see and feel that this is happening. So polluters have turned to other tactics and, ironically, one of them has been doomism. If they can convince us it’s too late to do anything, then why do so?”

Mann says he had noticed how climate history was being weaponised by doomers. “This idea that these past mass extinction events translate to ensured mass extinction today because of, for example, runaway methane-driven warming [as permafrost thaws] isn’t true – the science doesn’t support that.”

Our climate fate hangs in the balance, Mann says: “There’s fairly compelling evidence from the past, combined with the information from climate models, that if we can keep warming below 1.5C then we can preserve this fragile moment. But if we go beyond 3C, it’s likely we can’t. In between is where we’re rolling the dice.” Today’s climate policies and action would lead to about 2.75C, while delivering all the pledges and targets set to date would mean 2C.

“So it’s a question of how bad we’re willing to let it get,” he says. “1.5C is already really bad but 3C is potentially civilisation-ending bad.”

Widespread heatwaves, wildfires and floods clearly linked to global heating have given urgency to the call for action, Mann says: “But urgency without agency just leads us towards despair and defeatism. That’s what the polluters would like, to take all those climate activists and move them from the frontlines to the sidelines.”

Ending the climate emergency is possible, Mann says: “We know that the obstacles to keeping warming below catastrophic levels are not yet physical and they’re not technological – they’re political. But there’s some pretty big political obstacles right now.”

“Here at Penn State, there’s so much anxiety, fear and despair, and grief even,” he says. “Some of it comes from the mistaken notion that it’s physically too late and I want to dispel that notion. But part of it comes from an understandable cynicism about our politics, and that’s a much bigger challenge.”

His assessment of a potential victory for Donald Trump in the 2024 US presidential election is stark, calling it “a move away from democracy towards fascism, and there is no path to meaningful climate action that goes through fascism rather than democratic governance”.

“We have to get out and vote, and young folks have to get out in huge numbers and vote,” Mann says. “If we do that, then we can elect politicians who will act on our behalf, rather than act as a rubber stamp for polluters.”

The UN’s major climate summit, Cop28, begins at the end of November and is being hosted by the United Arab Emirates, which Mann calls “very disturbing”. The UAE has the third biggest net zero-busting plans for oil and gas expansion in the world and the president of Cop28 is also the CEO of Adnoc, the UAE’s state oil company.

“It just feels wrong to allow them to adopt the imprimatur of global climate action by hosting Cop28,” Mann says. “It is legitimising behaviour on their part and on the part of other petro states that is fundamentally at odds with the task we have ahead. I find it very disturbing.”

Mann has been a top target of climate deniers since the publication of the hockey stick chart. He is scathing about Elon Musk’s running of the social media platform X, formerly called Twitter.

“Musk used to be held out as an environmental hero, because of his role with Tesla,” Mann says. “But increasingly, he’s shown his true colours, his political allegiance to Trump and fascism.”

“Twitter was a global public square, a forum for communicating about the climate crisis,” he says. “What Musk has done is turn it into a toxic forum for the promotion of climate denialism and everything that’s bad in the world. It’s stunning.” Mann noted that Prince Alwaleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia, one of the “worst petro state actors”, played a $1.9bn role in Musk’s purchase of Twitter.

Mann also pointed out that Prince Alwaleed was a key backer of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire until 2017. “Rupert Murdoch has weaponised his global media network for the promotion of climate denialism and to attack renewable energy, which plays to his ideology and to the interests of some of the powerful petro-states, specifically Saudi Arabia.”

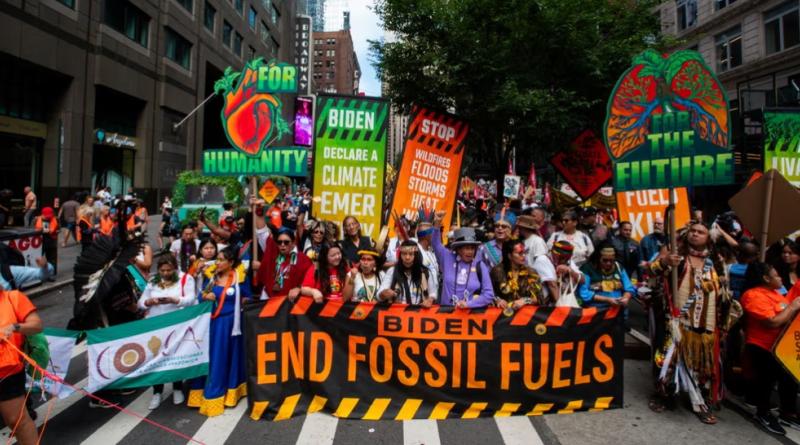

Photograph: Eduardo Muñoz/Reuters - Activists kick off Climate Week on 12 September 2023 with a protest against fossil fuels in New York.