‘We relied on the lake. Now it’s killing us’: climate crisis threatens future of Kenya’s El Molo people

Lake Turkana’s shores have been home to the El Molo for millennia but as rising waters swallow homes and sacred sites they face losing everything

Mombasa Lenapir briefly strokes the waters of Kenya’s Lake Turkana with his hand as he boards the rickety canoe. A piece of hippo tooth or kalate, dangles from his right earlobe, evidence that he once killed a hippo in his younger years, a rite of passage.

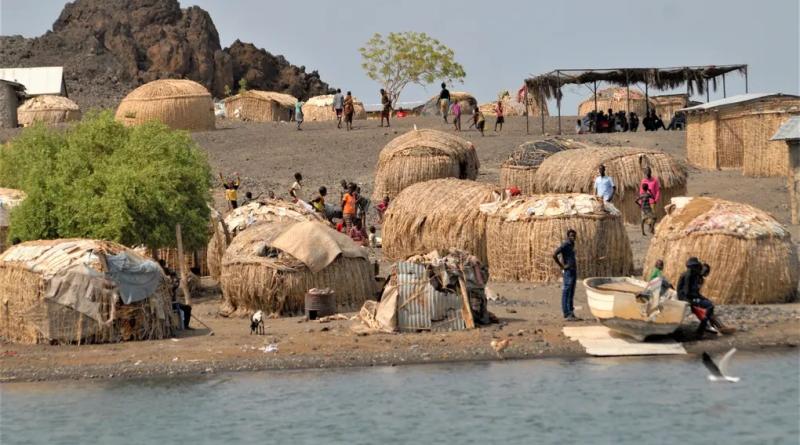

Lenapir is 70 and looks older, one of the El Molo community that has lived on the shores of Lake Turkana for millennia. Two years ago, he had to leave his home when rising waters engulfed his village, Komote, turning it into an island. Fearing being marooned by the expanding lake, Lenapir and other families built new homes on the mainland, while some opted to remain on the new island and use canoes to travel between the two settlements.

“Can you believe we are riding on what was once dry land?” says Lenapir. “I have never seen the water rise to this level. Children used to walk to school and play in a field, now under water, a few years ago. In the past, you could have driven up to these homes. Now parents have to pay boat owners for their children to get to school. It is difficult for the sick to get medical assistance, especially at night,” says Lenapir.

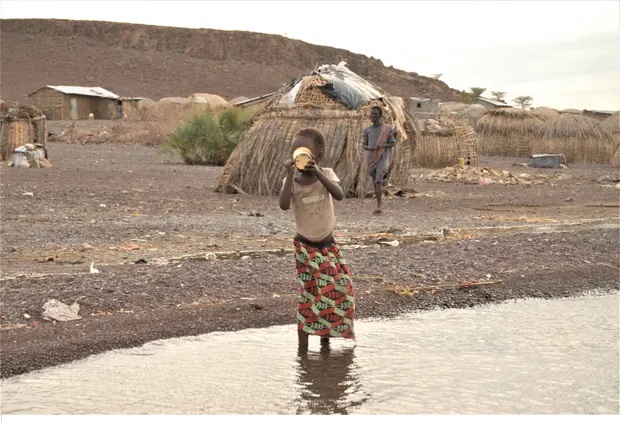

Another big loss for the community was a water pumping station that used to supply freshwater but now lies beneath the surface of the lake, forcing the El Molo people to rely on one of the most saline lakes in Africa for their water instead. The high levels of fluoride discolour teeth and weaken bones. Children, in particular, are prone to water-borne diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera and typhoid.

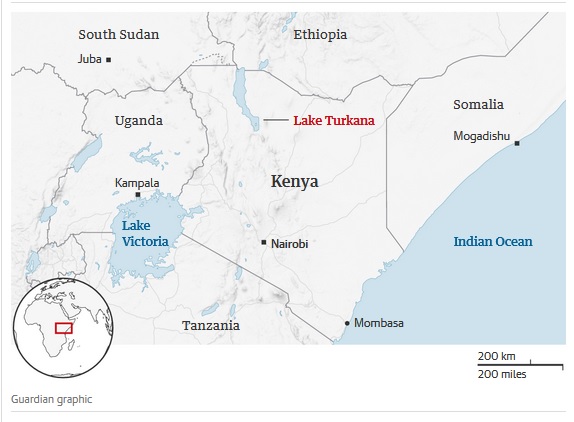

Surrounded by a barren landscape and dotted with black volcanic rocks, Lake Turkana, a Unesco world heritage site, has increased in area by more than 10% over the last decade, submerging close to 800 sq km of land. It has obliterated El Molo’s fishing sites, destroyed freshwater infrastructure, engulfed burial grounds and brought the community in proximity with ferocious Nile crocodiles, hippos and snakes.

A government-sanctioned report, published in 2021, says the rise in water levels in Lake Turkana and other Rift valley lakes is due to increased rainfall in the lakes’ catchment areas over the last few years, unsustainable land-use practices leading to soil in runoff water and geological activities within the Rift valley system.

A 2021 UN Environment Programme report stated how the climate crisis will lead to heavier rains over the lake’s key river inflows creating a further rise in the water levels over the next 20 years, with more social, cultural and economic impacts for nearby communities such as the El Molo.

“Such a possible increase in inflow will result in an increasing water level in Lake Turkana. Thus, the flooding which occurred in 2020, which was considered a rare event, is likely to become more regular in the future without any adaptation measures. The new evidence of continuing rising lake water levels is partially based on climate change scenarios and a predicted change in rainfall patterns,” says the report.

With an estimated population of 1,000, the El Molo were already living on the edge. Their language is listed as extinct by Unesco’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, as there is no known native El Molo who can fluently speak the dialect. El Molos belong to the Cushite ethnic group, but intermarriages between the tribe and nearby Nilotic communities, such as the Turkana and Samburu, have contributed to the language’s disappearance. Its future now lies with schoolchildren who are learning to speak a rudimentary form through a grammar book and folklore.

The El Molo are said to have originated from Ethiopia before settling in about 1,000BC on the shores of Lake Turkana in Kenya. Their diet consists largely of fish caught using traditional spears, harpoons and nets. The expanding lake has affected their key source of livelihood.

“Rising waters mean more fish are now found deeper into the lake. It is too windy to venture further offshore since our boats can capsize easily. We have lost a few of our members through such incidents. Without a good daily supply of fish, our lives are in danger since we cannot farm as the whole place is rocky,” says Julius Loyok, a local tour guide.

After 20 minutes, Loyok helps anchor the canoe on the shoreline of Komote island, before helping Lenapir to disembark. Bypassing homesteads, they head to some traditional shrines known as gantes, where older men like Lenapir offer sacrifices when a tragedy hits the community, to curse enemy tribes, pray for the rain and protection from snake bites. There are fears that if the lake continues to expand, the revered shrines, lying close to the water’s edge, will become inaccessible.

“Our language is dead, our culture is going and our homes are being swallowed by the water,” says Lenapir.

In neighbouring Layeni village, the water almost laps some homes, and half of the graves in the community burial site lie submerged. It is only a matter of time before the other half, a few metres from the lake, are submerged too. In a community where the dead are revered, the sight of the graves under water is particularly distressing.

“This is painful. Sometimes you need moments of solitude here. But now I have to ride a canoe with other people to reach the submerged graves. We buried the dead and now the graves are buried too,” says Lenapir.

A few miles from the El Molo villages, the Desert museum houses several artefacts belonging to the community, such as food and tobacco containers and tortoise shells used as plates.

Ntalan Ogom, the museum’s caretaker and a member of the El Molo community, says this is perhaps the only place where future generations will learn of a lost tribe, an extinct language and a dying culture. “We relied on the lake to live. Now it’s killing our people.”

cover photo: Komote village was turned into an island when the waters of Lake Turkana engulfed it in 2020. Photograph: Peter Muiruri/The Guardian