The US has left the Paris climate deal — what’s next?

Other nations are stepping up targets to reduce emissions — but the world will struggle to meet its goals.

Regardless of who wins the US presidential election, the United States officially pulls out of the Paris climate agreement on 4 November. The move marks a blow to international efforts to halt global warming.

The landmark deal, struck in 2015, aims to limit global warming to “well below” 2 °C above pre-industrial temperatures. But in June 2017, US President Donald Trump announced that the United States — the world’s second largest emitter of greenhouse gases — would withdraw from the agreement.

Nature examines how the withdrawal will affect global efforts to mitigate climate change.

What is Trump’s climate legacy?

Trump’s decision to pull out of the landmark accord was the first major step in his campaign to systematically roll back US federal climate policies set up during the administration of Barack Obama.

Trump has since reversed dozens of climate-related regulations, including rules on air pollution, emissions, drilling and oil and gas extraction. During his first term as president, and in his re-election campaign, he made no secret of his preference for fossil fuels and the industry which provides them. A report by the US energy department, released last month, lauds oil and gas as “providing energy security and supporting our quality of life”, without mentioning climate risks related to persistent use of carbon-rich fuels.

Although the United States played a major part in crafting the climate agreement, it will be the only one out of the nearly 200 parties to pull out of the pact.

Which countries are taking the lead on climate-change mitigation?

China and the European Union have picked up the pieces. In September, China, the world’s top emitter of greenhouse gases, announced a bold plan to make its economy carbon neutral by 2060, using a combination of renewable energy, nuclear power and carbon capture. Likewise, the EU’s Green Deal, first announced in December 2019, sets out a road map for making the bloc carbon neutral by 2050. Compared with 1990 levels, the EU has already reduced its greenhouse-gas emissions by 24%. Legislation intended to achieve full carbon neutrality by the middle of the century is under discussion.

Other major economies, such as Japan and South Korea, pledged last month to become carbon neutral by 2050, but haven’t spelt out in detail how they will achieve it. In all, more than 60 countries worldwide — including all EU member states except Poland — have committed to achieving net-zero emissions by mid-century.

But without the United States, the balance among parties signed up to the Paris accord shifts in China’s favour on key issues that are yet to be settled. In particular, China could resist calls for detailed tracking and reporting of how countries are implementing policies and achieving their goals, says Michael Oppenheimer, a climate-policy researcher at Princeton University in New Jersey. “That bodes poorly for the effectiveness of the Paris agreement,” he says.

Neither China nor the EU can fully make up for the gap the United States has left, says Susanne Dröge, a policy specialist at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin. “Leadership is not only about ambitious announcements, but also about a credible economic climate agenda as well as international cooperation,” she says.

Can the world cope with the US withdrawal?

The task will become harder. Although high-emitting countries are increasingly keen to curb global warming, experts warn that current climate and energy policies are not enough to keep the world below 2 °C of warming. There has been a marked drop in greenhouse-gas emissions this year — because of reduced travel and economic activity during the coronavirus pandemic — but that will do little to get the world nearer to its climate goal, experts caution.

Rising green-energy ambitions are some cause for hope. Globally, more energy is being produced from renewable sources each year. But analysts say that many countries, including the United States, are still pursuing energy strategies that prioritize and subsidize fossil fuels. And the amount of energy being made from fossil fuels is increasing, the International Energy Agency said in its latest World Energy Outlook, published last month.

“Green energy is not yet replacing fossil fuels — it is merely augmenting it,” says Timothy Lenton, a climate researcher at the University of Exeter, UK.

So what’s next?

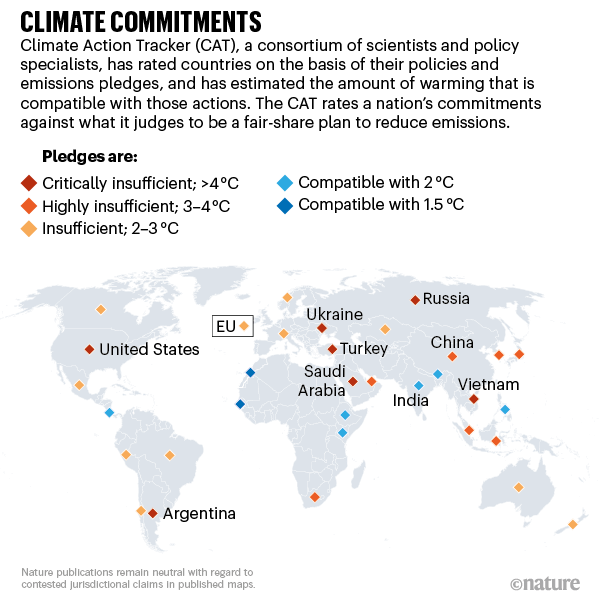

Parties to the Paris accord have agreed to update their targets for 2030 in line with the latest evidence on the world’s remaining carbon budget. A special report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on keeping warming to 1.5 °C, completed in 2018, made clear that the climate targets that countries think they can meet are not sufficient to halt global warming (see ‘Climate commitments’).

All remaining parties to the agreement must submit their new 2030 targets before the next major United Nations climate meeting, set to take place in Glasgow, UK, in November 2021 (this year’s climate summit was postponed because of the pandemic). So far, only 14 have proposed or submitted revised targets.

“The US withdrawal, if it is sustained by the next administration, will inevitably cause some countries to reduce their level of effort on implementing existing commitments,” says Oppenheimer.

Might a new president get the United States back on board?

Democratic candidate Joe Biden has said that if he is voted president, he will rejoin the Paris accord early in his presidency. The United States could once more become a party to the Paris agreement 30 days after officially informing the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that it wants to rejoin. The country would then need to submit a new emissions-reduction pledge for 2030.

Before Trump took power, the United States had committed to reducing emissions by 26–28% below 2005 levels by 2025 — a target that it is not on track to meet. Biden has promised to invest almost US$2 trillion in clean energy and low-carbon infrastructure, but he has not said what emissions-reduction target he might set if he becomes president.

Whatever happens, the country will have lost credibility on climate action, says Oppenheimer. “The United States can’t simply jump back in and pretend it’s all back to 2015,” he says. “It will need to work to regain trust.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03066-x

4 November 2020

nature