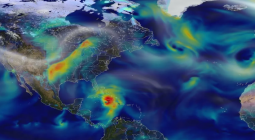

Tropical cyclones have become more destructive over past 40 years, data shows.

US study identifies statistically significant trend in line with climate scientists’ predictions.

Tropical cyclones have become more intense around the globe in the past four decades, with more destructive storms forming more often, according to a study that further confirms the theory that warming oceans would drive more dangerous cyclones.

Analysis of satellite records from 1979 to 2017 found a clear rise in the most destructive cyclones – also known as hurricanes or typhoons – that deliver sustained winds in excess of about 185km/h.

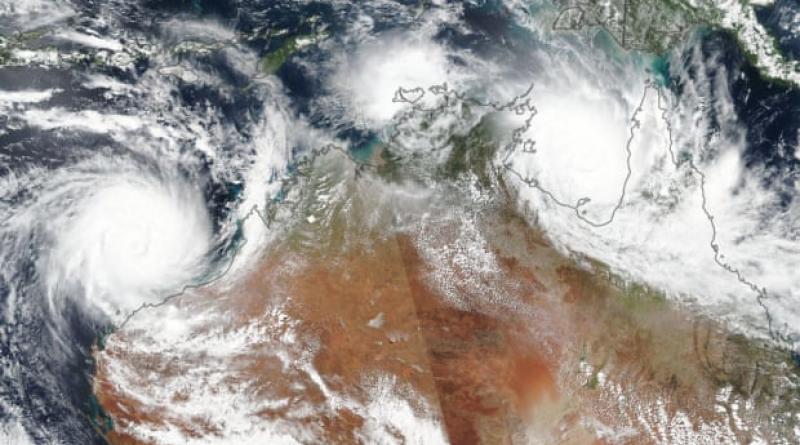

Australia sits across two ocean basins where cyclones form – the southern Indian Ocean and southern Pacific Ocean – where the study also identified rising trends of the more destructive storms.

Experts told Guardian Australia the finding was in line with climate model predictions and the knowledge that increasing ocean temperatures gave tropical storms more energy.

Dr Hamish Ramsay, a senior research scientist at CSIRO who studies cyclones, said: “This study confirms what the climate models have been predicting for some time – that the proportion of the most intense storms will increase as the climate warms.”

While climate scientists have long-predicted that global heating would deliver stronger cyclones, a trend that was statistically significant has been challenging to identify in part due to the natural swings in the world’s climate masking changes.

Published in the leading journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study was carried out by scientists at the US government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The scientists did not try to find a cause for the increase in more dangerous cyclones, but said the trends were consistent with understanding of physics and modelling, and the finding “increases confidence that [tropical cyclones] have become substantially stronger, and that there is a likely human fingerprint on this increase”.

The probability of a cyclone reaching wind speeds greater than 185km/h had risen by about 15% over the 39 years studied.

A previous study of the same data had only spanned a shorter period from 1982 to 2009 and, while positive trends had been found, they were statistically not at significant levels, the study said.

As well as looking at the number of cyclones forming globally, the study also looked at changes in cyclone intensity by region. The southern Indian Ocean and the southern pacific Ocean both showed an increase in the number of the more intense storms, although the trends in each individual region were not as robust due to the smaller number of cyclones.

“[The study] suggests that the climate change signal in the data is potentially already emerging and this is something that climate scientists have been saying for some time,” Ramsay said. “We maybe at a point now where we are starting to evidence from observational data that supports what the models have been telling us.”

Ramsay said as well as increasing the wind speeds in cyclones, warming oceans would also likely see cyclones delivering more rainfall. There was still uncertainty as to whether the numbers of all categories of cyclones would rise or fall under climate change.

Australia’s 2018 State of the Climate Report said since 1982 there had been a downward trend in the number of all tropical cyclones in the Australian region but it was not possible to see any trend in the intensity of cyclones.

Previous research has found that when cyclones form, they are tending to move more slowly, while delivering more rain.

Dr Greg Holland, a senior scientist emeritus at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, has studied cyclones for about 40 years.

The Melbourne-based scientist said while there were legitimate arguments over the finer details of trends and intensity in relation to tropical cyclones: “The work all points in the same direction – the proportion of the most intense cyclones is going up.”

He said: “There is nobody saying the trend will go the other way. The physics has been well set out for 30 or 40 years. If you get a warmer ocean then the intensities of cyclones goes up. That’s a 5% or 10% increase in maximum winds for every 1C of warming in the ocean. The world is warming and its because we have put more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

“For the Australian region – which is the eastern Indian and southern west Pacific – it means we now have the potential for there to be more intense tropical cyclones coming ashore and doing more damage.

“The chances of us getting an intense cyclone have gone up already and they will go up in the future.”

Holland said there was also evidence that the ocean region of Australia where intense cyclones could strike was also expanding. The observed movement was only about 150km, he said, but this would soon put Brisbane “in the cyclone zone”.

Prof Steven Sherwood, of the UNSW Climate Change Research Centre, said the study was important “because it shows that the upward trends first reported about a decade ago in cyclone activity have been sustained, and have now gone on long enough that it is no longer possible for them to be a random natural variation.”

He said the study found that averaged globally, 30% of cyclones in the 1980s were “major” compared with 40% of cyclones now.

“There is of course nothing surprising about this — we’ve just reached the point of ‘non-deniability’,” he said.

“The implication for Australia is that our risk exposure to strong cyclones will almost certainly continue to increase as long as global temperatures increase.

“It also appears that storms are encroaching farther away from the equator, although this is harder to confirm observationally. If this is true, it means that the Queensland southern coast in particular may be at growing risk.”

20 May 2020

The Guardian