‘Towns were erased’: Libyan reporters on the ‘horrifying, harrowing’ aftermath of floods

Journalists who reported on last week’s catastrophic storm say the country’s bloody political tussle has contributed to the collapse of services

Early last week, Mohamed Eljabo, an independent journalist from Tripoli, travelled to the eastern provinces of Libya, passing through Derna, Al Bayda and Sousa, and what he saw he describes as “shock beyond comprehension”.

“I have visited these cities before and I know them well,” he says. “I expected to find these cities when I made the journey from Tripoli. I expected to see the neighbourhoods and towns. But these were gone. Erased. It was horrifying.”

Eljabo is one of many local reporters who have in the last week witnessed scenes they now find it hard to describe and are struggling to process. The Observer spoke to six journalists who have between them narrowly escaped death, experienced the loss of friends and loved ones and reported from places now almost wiped off the map.

“The most haunting part of the whole experience was the scar the storm has left on the living,” says Eljabo. “When I began working on a report and interacted with survivors, their faces screamed of fear. The horror was tangible in their eyes, their features. There were children crying over the graves of their families and trying to climb into the graves. I have never experienced something as harrowing as this.”

Noura Mahmoud al-Haddad, an independent journalist in the city of al-Shahat, 100km from Derna, watched from her windows as the rain came down for almost 24 hours, causing the power to go out and water to fill the streets as high as the second storey of the city’s buildings.

“It was a catastrophic night. We almost died drowning. I even posted on my Facebook page my end and bid farewell to my family before going to bed. I expected to die with my three children, whom I placed next to me in bed,” says Haddad.

The floodwaters have wreaked havoc in Derna and surrounding areas, leaving behind bodies on beaches, streets and beneath the rubble. According to the United Nations, local authorities concerned about disease spreading have hurriedly buried 1,000 people in mass graves.

The World Health Organization and others have had to warn against this rush, saying there was no additional threat of disease but that clean drinking water was a priority because the water will be contaminated.

There is also concern about the movement of undetonated explosives being shifted around by the floodwaters, having already killed 3,457 people in Libya since the civil war, according to Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor.

The Libyan Red Crescent has said that 11,000 people have died in Derna and more than 10,000 are missing. Rescuers are having to dig through the mud to search for more bodies while a slow evacuation of remaining residents is ongoing. While western Libya is controlled by a UN-backed government, the affected areas in eastern Libya have been ruled over for much of the past decade by the warlord Gen Khalifa Haftar.

For the journalists who lived through and reported the floods, the bloody political tussle has contributed to the degradation of the country’s services, including the lack of maintenance to the 1970s-era dams in Derna that crumbled. They, like others in the disaster zone, are angry about how a catastrophe on this scale was allowed to happen.

“I tried while covering the events for local and international media to stay neutral and to describe the situation accurately. But I am not quite sure I was able to,” says Hendia Hamdy Alashepy, an independent journalist from Benghazi, the largest city in eastern Libya.

The responsibility for trying to clear up some of the confusion ended up falling on the shoulders of Mohamed Gurj, a correspondent for the Ahrar Libya TV channel, who set up a WhatsApp group to connect journalists to each other as well as government officials.

An experienced reporter who thought he had seen everything since the beginning of the civil war in 2011, and was even kidnapped that year by an armed group, the devastation caused by the flooding shocked Gurj and he was determined to act. But he found managing the group, and the tensions between civilians and the officials, overwhelming.

“I found myself responsible, in one way or another, for managing the crisis that occurred, linking relations between all parties, and managing the disaster and all the teams. After a day and a half of this pressure, I collapsed at home and fainted. I had not eaten anything or slept since the crisis began,” says Gurj.

His wife Zainab Jibril, also a journalist, spent the entire time trying to contact missing friends. “The news finally came in that most of my friends were fine. They managed to survive but they lost their families. My friends survived but they came back as different individuals. Different from the magnitude of the shock,” says Jibril.

Despite the tragedy he has witnessed, Gurj says he is proud that the work done through the WhatsApp group helped save lives and communicate what Libya needs.

The form of help that now comes to the country is on the minds of these Libyan journalists, who had covered the country’s problems during times of war and rival governments even before the flooding.

They are less concerned about the short-term need for food and aid but say Libya needs help with rebuilding. Haddad says for the people of Derna, who do not want to leave the city behind, it is a priority to rebuild the dams that were destroyed while Eljabo says expertise is needed.

“Libyans today do not need resources. We have plenty. What we need is expertise - the technical experience and trained rescuers. We need the world to send over their experienced rescuers, and skilled specialists. We need the world to lend us a hand,” he said.

The recovery will be reported on by the same Libyan journalists who had to sit through the storm itself, like Derna-based journalist Moataz el-Hasi, who has barely eaten or spoken since, his mind replaying the scenes he has witnessed.

“But it’s our job and I’ll be back in the field in a few hours because this is the least we can do: show the world what Libya is going through, let it know how they can help,” he says.

The testimonials were gathered by Egab, an organisation that works with local journalists across the Middle East And Africa

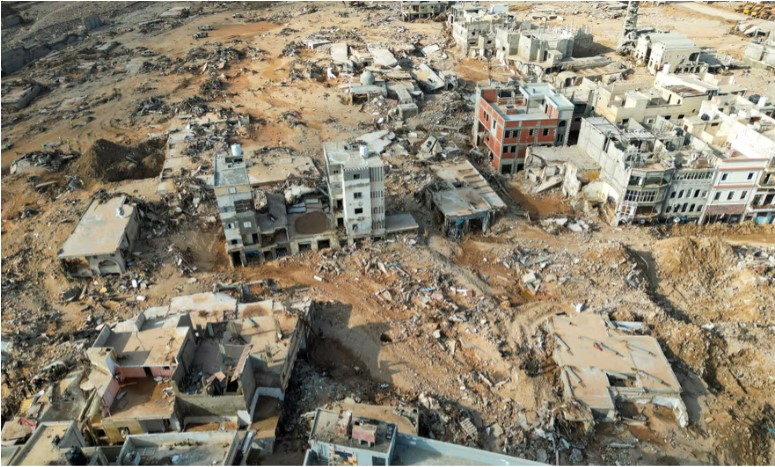

Photograph: Ayman Al-Sahili/Reuters - Rescue teams and members of Libyan Red Crescent search for dead bodies at a beach in the aftermath of the floods in Derna.