Remembering Mario Molina, Nobel Prize-winning chemist who pushed Mexico on clean energy – and, recently, face masks.

Dr. Mario Molina, the Nobel Prize-winning scientist who died on Oct. 7 at age 77, did not become a scientist to change the world; he just loved chemistry. Born in Mexico City in 1943, Molina as a young boy conducted home experiments with contaminated water just for the fun of it.

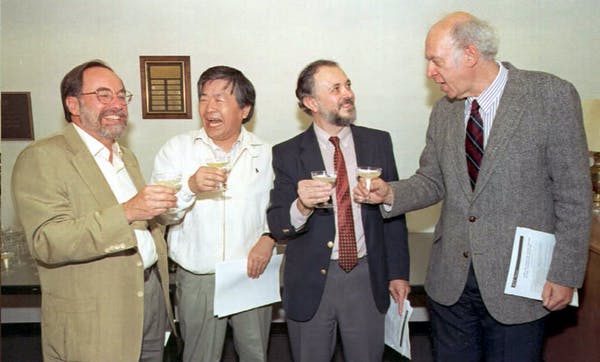

But Molina came to understand the political importance of his work on atmospheric chemistry and ozone layer depletion, which won him the Nobel in 1995, along with Paul J. Crutzen and F. Sherwood Rowland. Getting that surprise call from Sweden completely changed how he saw his role in the world, Molina said in 2016. He felt a responsibility to share his knowledge of clean energy, air quality and climate change broadly and to push decision-makers to use that information to protect the environment.

As a Mexican, Dr. Molina was a point of pride for me. Though I am a social scientist, not a chemist, his career inspired me to follow my dreams and to trust science to show us all the right path.

Clean air now

Mario Molina thought climate change was the biggest problem in the world long before most people did.

His research was instrumental in spurring negotiation of the 1987 Montreal Protocol, an international treaty that effectively banned fluorocarbons – harmful chemical compounds that damage the ozone layer. The agreement is credited with helping the ozone layer heal. He understood that the environmental problem is global, and that what happens in China or the United States affects Mexico, too.

After a long a career in academia, Molina and his wife, Luisa T. Molina – also an an atmospheric scientist – founded the Centro Mario Molina in 2005, a Mexican center dedicated to environmental research and public policy. Together, they co-directed the center, which conducts extensive work in Mexico City.

The Molinas sounded the alarm in Latin America about air pollution and public health, which remains a challenge in the region. But they also understood the role of economics in environmental protection – and, importantly, the centrality of fossil fuels to the Mexican economy – so the Molinas worked with Mexican economists to address concerns that green energy would hurt prosperity.

Through his organization, Molina also promoted cooperation between scientists, goverment, industry and civil society until 2013, when then-Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto appointed him to head the country’s National System for Climate Change.

In 2018, when Mexico’s government changed, Molina was not invited to serve in the new administration. Mexico’s current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, came to power promising to build a new oil refinery in Mexico.

Molina urged Mexico to transition to clean energy sources “sooner rather than later,” promising this policy change would promote “public health, job creation and energy security for the country.” In a May 2020 interview, Molina stressed clean energy “is an investment that society makes and very profitable.”

“Mexico is going back to the previous century or the one before it, at a time when all the experts on the planet fully agree that we are in a climate crisis,” he said of Mexico’s continued reliance on fossil fuels just months before his death. Molina criticized López Obrador for limiting the use of clean energy sources and pushed for more wind energy in Mexico, a technology that’s only just emerging there.

Scientist until the end

Molina defended the importance of science in policy-making until the very end.

When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, he was an early and adamant advocate for face masks and was aghast that the presidents of both Mexico and the United States refused to wear facial coverings. He said the government should “force the use of face masks…because only in this way do we know that the curve can be flattened.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Mario Molina graduated from the National Autonomous University of Mexico, or UNAM, and completed his graduate studies at the University of Fribourg and the University of California, Berkeley. Though he taught at M.I.T., he remained loyal to UNAM, working with faculty and students til the end.

The many Mexicans who, like me, were inspired by his life’s work mourn his passing.

10 October 2020

THE CONVERSATION