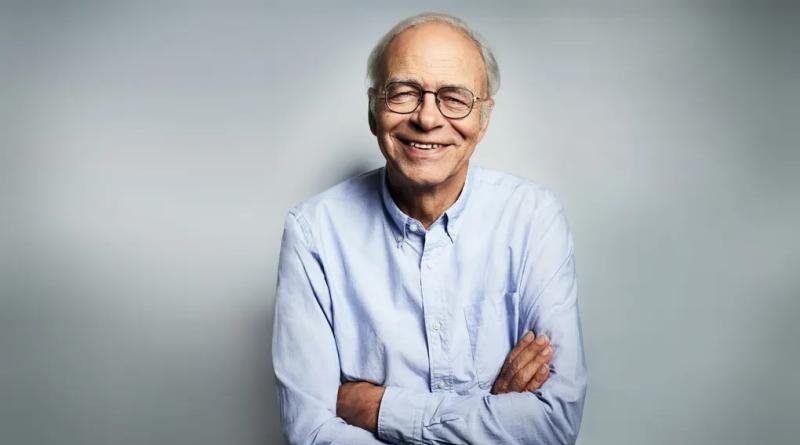

Philosopher Peter Singer: ‘There’s no reason to say humans have more worth or moral status than animals’

Australian philosopher Peter Singer’s book Animal Liberation, published in 1975, exposed the realities of life for animals in factory farms and testing laboratories and provided a powerful moral basis for rethinking our relationship to them. Now, nearly 50 years on, Singer, 76, has a revised version titled Animal Liberation Now. It comes on the heels of an updated edition of his popular Ethics in the Real World, a collection of short essays dissecting important current events, first published in 2016. Singer, a utilitarian, is a professor of bioethics at Princeton University. In addition to his work on animal ethics, he is also regarded as the philosophical originator of a philanthropic social movement known as effective altruism, which argues for weighing up causes to achieve the most good. He is considered one of the world’s most influential – and controversial – philosophers.

Why write Animal Liberation Now?

The last full update was 1990. Though the philosophical arguments have stood up well, the chapters that describe factory farming and what we do to animals in labs needed to be almost completely rewritten. I also hadn’t really discussed factory farming’s contribution to the climate crisis and I wanted to reflect on our progress towards animal rights. Effectively, this is a new book for the next generation, hence the new title.

What progress have we made in our treatment of animals since the original book? And what have we learned about animal sentience?

There have been some improvements in factory farming practices in some regions of the world, but in others we have hit new lows. China now has enormous factory farms and lacks any national standards for raising animals for food. Extreme forms of confinement also still dominate the US states with the most pigs and laying hens. Animal experimentation is now regulated in many developed nations, but what’s notable is how minimal it is in the US, where the vast majority of animals used in experiments aren’t covered. On animal sentience, we now have strong evidence that fish too can feel pain. There are also good reasons for thinking the same of some invertebrates – the octopus but also lobsters and crabs. How far sentience extends into other invertebrates is unclear.Can you explain your position against speciesism, the belief most humans hold that we are superior to other animals? Shouldn’t humans count more?

Just as we accept that race or sex isn’t a reason for a person counting more, I don’t think the species of a being is a reason for counting more than another being. What is important is the capacity to suffer and to enjoy life. We should give equal consideration to the similar interests of all sentient beings. Defenders of speciesism argue that humans have a special rational nature that sets them apart from animals, but the problem is where that leaves infants and the profoundly intellectually disabled. Instead of defending the idea that all humans have rights but no animals do, we should recognise that many things we do to animals cause so much pain and yet are so inessential to us that we ought to refrain. We can be against speciesism and still favour beings with higher cognitive capacities, which most humans have – but that is drawing a line for a different reason. If there are animals that have higher cognitive capacities than some humans, there’s no reason to say that the humans have more worth or moral status simply because they are human.The chapters in Animal Liberation Now about animal testing and factory farming are upsetting to read. Were they upsetting to write and rewrite and what pulled you through?

I found them very upsetting, both 48 years ago and as I’ve worked on them over the past year. But I also felt driven to complete them so people know and can help stop it. I’ve had to develop a thicker skin and sometimes have had trouble getting to sleep, but it needed to be done. I do steer away from emotive language. I’ve never considered myself an animal lover and I don’t want to only appeal to animal lovers. I want people to see this as a basic moral wrong.

You have provoked the ire of the disability rights advocates over the years, including by arguing that parents should have the right the end the lives of severely disabled newborns. This has been criticised as an ableist view that could lead to other disabled people being less valued. What’s your response?

In general, I think it is better to have abilities than not to have them. Most people hold that view. Obviously, there are forms of discrimination against disabled people that we should firmly reject. Ableism has a sound purpose when it calls out discrimination against disabled people on grounds not related to their disability.

If parents have a newborn with a severe disability and that child needs to be on a respirator to survive, doctors will invite parents to decide whether to allow the child to die. That happens regularly and is generally uncontroversial. Yet it is what the child’s future will be like that is really relevant. And I think, even in cases where the child doesn’t need a respirator, parents should be able to consult doctors to reach a considered judgment, including that the child’s life is not one that is going to be a benefit for the child or for their family, and that therefore it is better to end the child’s life. If that is ableist, then it isn’t always wrong to be ableist.

You argue there are certain situations where we could replace the animals we experiment on with humans…

During the Covid pandemic, I supported 1Day Sooner, an organisation of well informed volunteers offering to test the efficacy of candidate vaccines. That could have saved many thousands of lives by speeding up vaccine introduction, but the volunteers were rejected. There is also a case for beneficially using humans in persistent vegetative states from which we can be absolutely clear that they will never recover. People could sign consent statements, as they do with organ donation, saying they don’t mind their body being used for research if that were to happen.

While effective altruism – the philanthropic social movement you helped originate – has its critics, it has gained a following in recent years, including in Silicon Valley tech circles (disgraced cryptocurrency founder Sam Bankman-Fried was prominent in the movement). One newer idea it has spawned is longtermism. It prioritises the distant future over the concerns of today and advocates reducing the risk of our extinction, for example, by thwarting the possibility of hostile artificial intelligence (AI) and colonising space. To what extent do you endorse longtermism?

We should think about the long-term future and we ought to try to reduce risks of extinction. Where I disagree with some effective altruists is how dominant longtermism should become in the movement. We need some balance between reducing the extinction risks and making the world a better place now. We shouldn’t negate our present problems or our relatively short-term future, not least because we can have much higher confidence that we can help people in these timeframes. Though the lives of people in the future aren’t of any less value, how we can best help people millennia from now is uncertain.Are you vegan and how did you first become concerned about animal suffering?

“Flexibly vegan” is how I would describe myself today. I don’t do it much, but I have no objection to eating oysters – I don’t think they can suffer – and oyster farming is quite an environmentally sustainable industry. Also, if I am out somewhere where it’s a real problem, I will go for something vegetarian. That my everyday purchases are vegan is the main thing.

My journey began when I was a graduate student in philosophy at Oxford University in 1970. It was thanks to another graduate student explaining why he hadn’t chosen the meat option when we had lunch one day: he was vegetarian because he didn’t think the animals were treated right. My wife and I did some reading and became vegetarians soon after. Becoming mostly vegan took longer.

Conscientious omnivores oppose factory farming but continue to eat animal products from farmers who treat their animals well and don’t subject them to suffering. Do they get a pass?

Honestly, I can’t show that they are wrong. Assume that the cows wouldn’t have existed if they weren’t going to be sold for their meat and the conscientious omnivores investigate how their food is produced, and can be confident that the animals really do have good lives and are killed painlessly and without suffering – then I think they do get a pass. They’re allies in the movement against factory farming, and a world of conscientious omnivores would produce much less meat and dairy products, with vastly less suffering.

What of meat grown from cultured animal cells?

That gets more than a pass and I hope to try it soon. What is needed now is to produce it cheaply at scale. It is much better for the climate than meat from animals and for animal suffering. And while it is true that it still suggests that meat is desirable, there are people who are unwilling to make that switch to becoming vegan or vegetarian. The companies’ use of fetal bovine serum to develop their products is regrettable and I am pleased that many companies have found alternatives and stopped using it, but if there are no alternatives, its use can be justified. I don’t regard it as a reason for never eating them.

You’ve brought vegan recipes back in Animal Liberation Now. Why resurrect them and do you have a particular favourite?

Popular demand! In 1975 there weren’t many good vegetarian or vegan cookbooks so it made sense to include recipes. Then, as that changed, I didn’t think people needed the recipes any more so I took them out. What I have put back is different. The focus is on my and my wife’s dishes. Both vegan recipes from our childhoods that we still make and then things we have started cooking since becoming mostly vegan. I have shifted to more Asian food and a favourite is the recipe for dal. It is a good meal and easy to make.

My journey began when I was a graduate student in philosophy at Oxford University in 1970. It was thanks to another graduate student explaining why he hadn’t chosen the meat option when we had lunch one day: he was vegetarian because he didn’t think the animals were treated right. My wife and I did some reading and became vegetarians soon after. Becoming mostly vegan took longer.

Conscientious omnivores oppose factory farming but continue to eat animal products from farmers who treat their animals well and don’t subject them to suffering. Do they get a pass?

Honestly, I can’t show that they are wrong. Assume that the cows wouldn’t have existed if they weren’t going to be sold for their meat and the conscientious omnivores investigate how their food is produced, and can be confident that the animals really do have good lives and are killed painlessly and without suffering – then I think they do get a pass. They’re allies in the movement against factory farming, and a world of conscientious omnivores would produce much less meat and dairy products, with vastly less suffering.

What of meat grown from cultured animal cells?

That gets more than a pass and I hope to try it soon. What is needed now is to produce it cheaply at scale. It is much better for the climate than meat from animals and for animal suffering. And while it is true that it still suggests that meat is desirable, there are people who are unwilling to make that switch to becoming vegan or vegetarian. The companies’ use of fetal bovine serum to develop their products is regrettable and I am pleased that many companies have found alternatives and stopped using it, but if there are no alternatives, its use can be justified. I don’t regard it as a reason for never eating them.

You’ve brought vegan recipes back in Animal Liberation Now. Why resurrect them and do you have a particular favourite?

Popular demand! In 1975 there weren’t many good vegetarian or vegan cookbooks so it made sense to include recipes. Then, as that changed, I didn’t think people needed the recipes any more so I took them out. What I have put back is different. The focus is on my and my wife’s dishes. Both vegan recipes from our childhoods that we still make and then things we have started cooking since becoming mostly vegan. I have shifted to more Asian food and a favourite is the recipe for dal. It is a good meal and easy to make.

cover photo:‘I’ve had to develop a thicker skin’: philosopher Peter Singer. Photograph: Alletta Vaandering