Nuclear is Getting Hammered by Green Power and the Pandemic.

Generating power without harmful carbon emissions has never been more urgent, yet one of the biggest sources of clean power is struggling to turn a profit.

The nuclear industry has been vying for a role as the perfect partner to the surging, but intermittent, renewables sector for years, citing its role as a stable source of emissions-free power. Nations around the world have set tough targets to reduce greenhouse gases with the help of clean energy to meet commitments set out in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Record output from wind and solar is more frequently creating an oversupply that can push prices below where reactors are no longer profitable, or even to rates where utilities have to hand out power for free. The rout has been exacerbated by the global pandemic gutting demand. Generators from France to Sweden, Germany and China have been forced to turn stations off or curb output.

“We need to work on being more flexible in nuclear,” Magnus Hall, the chief executive officer of Swedish utility Vattenfall AB said in an interview. “It’s a new way of learning how to run the plants and this is the mode we are in.”

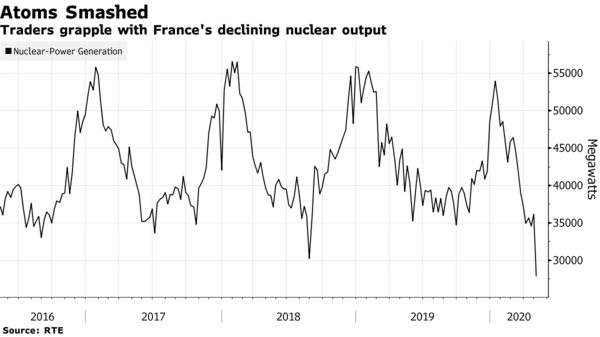

Electricite de France SA, the world’s biggest nuclear operator, is feeling the heat more than most. The utility with 57 domestic reactors and new-build projects at home and abroad, expects output from its stations in the country to fall by more than a fifth this year.

Its output is near the lowest since at least 2012 after about a dozen plants were taken offline in April. The utility’s shares are trading close to a record low.

“The current period foreshadows an energy mix with a more important role for renewables,” Etienne Dutheil, director of nuclear production at EDF, said in an interview. “It shows the necessity for other production means, and for nuclear in particular, to be flexible, which is the case for the French fleet.”

In Sweden, where the technology has provided a stable supply for its energy-intensive factories for decades, two reactors at Vattenfall’s Ringhals plant are idle because prices are below the level where they break even for most of the time. Others have been forced to reduce output.

Vattenfall’s profit from power generation (excluding trading) slumped 39% in the first quarter and the company cut the dividend to its state owner by half, citing the impact of weak prices and the pandemic. Ukraine on Monday cut its annual nuclear power output forecast because of the virus lockdown.

As electricity demand collapsed across the world because of lockdowns, renewables have taken a bigger slice of the market because many nations had decided to give new green technologies priority into the grid.

For many years, European atomic reactors churned out electricity around the clock and lived in a happy coexistence with fossil-fuel plants firing on coal and gas. There was enough demand for everyone. Most of the nuclear plants were built in the 1970s and 1980s so utilities had paid for them already. That meant low operating costs.

The impact of sun and wind on the power market was negligible until German Chancellor Angela Merkel launched early this century her so-called Energiewende with heavily subsidized green power. The program, which came at a cost of hundreds of billions of euros for taxpayers, inspired many nations around the world to also expand into renewables. The shift has rewritten energy economics and given solar and wind a major role.

“The life of everyone else does get that bit more challenging,” said Peter Osbaldstone, research director, European power and renewables at Wood Mackenzie Group Ltd. “When you take it to the extreme, you get generators not designed to provide flexibility having to provide flexibility and that’s where nuclear finds itself.”

While U.S. nuclear operators aren’t forced to ramp down output akin to their European peers, plants that can’t compete in the market have gradually shut down. With prices in a rut, eight stations have gone dark since 2013. At least four more are scheduled to close permanently by 2025, including after one unit north of New York City shut at the end of April.

In China, the coronavirus caused reduced output at CGN Power Co.’s atomic plants after the Lunar New Year holiday. Without taking into account the two reactors that came into operation in 2019, output at the remaining 22 units fell 4.7% in the first quarter from a year earlier, the company said.

After correcting for weather effects, full lockdowns reduced daily electricity demand by at least 15% in France, India, Italy, Spain, the U.K. and northwest U.S., the International Energy Agency said in a report on April 30. Global power consumption will decline as much as 5% this year, or the most since the Great Depression, according to the group advising the richest nations.

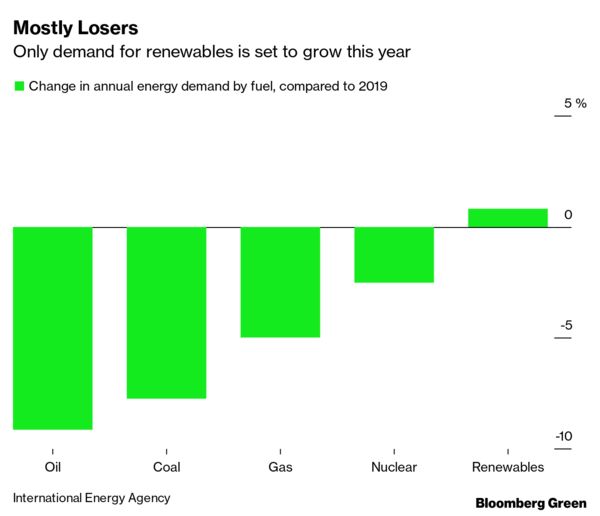

That will hurt all power sources, although use of renewables will still post a 1% gain this year, IEA said. Nuclear could drop by 3% from 2019 due to lower demand and delays to planned maintenance and construction of several projects, IEA said.

For example, EDF’s U.K. unit is undertaking more work than usual at its reactors, with five out of 15 units halted for long-term repairs. Output is below normal for the time of year. The company declined to comment on whether it was altering production due to rising renewables.

Still, with 2,821 terawatt-hours generated globally, atomic stations produced about a third more electricity than solar and wind in 2019, according to preliminary data from BloombergNEF. That’s enough to supply all of Germany for about five years.

And the nuclear industry is standing firm. As many as 55 plants are under construction globally, according to Agneta Rising, director general of the World Nuclear Association.

“It’s very challenging times, but nuclear is the backbone of the electricity system,” she said in an interview. “This is a super strange situation and that means you have to take some reactors offline.” But, unlike wind and solar, “if they are needed they are always there.”

The technology also has the advantage of being a domestic energy source and “that is something governments want to have,” said Rising.

At Vattenfall, workers will permanently shut another old reactor at Ringhals by the end of the year, just after one unit was closed down in December. It would have been too costly to make the investments needed to keep them running any longer, the company has said.

And Hall, the boss, has a clear vision. While 5 billion kronor ($510 million) will be invested to secure safe operations at its nuclear and hydro plants this year and next, as much as 25 billion kronor will go to wind.

“We want to build more fossil-free generation and that is predominantly wind.”

(An earlier version of this story corrected the spelling of Energiewende in 12th paragraph.)

— With assistance by Francois De Beaupuy, Feifei Shen, Vanessa Dezem, and Will Wade

4 May 2020

Bloomberg Green