‘No easy fix’: polar bear capital of the world turns to electric buggies to save the bears

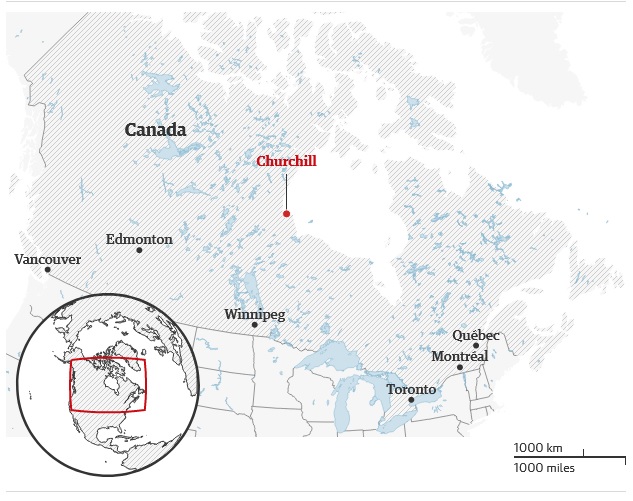

The move comes as Churchill, Canada, remained ice free for the first time in years, resulting in less feeding time for its population of polar bears

When tourists reach the north Canadian community of Churchill they have long been greeted by two sounds: the howling of sub-Arctic winds and the rattle of diesel engines.

Over the years, hundreds of thousands of visitors have come to the “polar bear capital of the world”, in the hopes of spotting the predators. They journey on “tundra buggies” – hulking, spacecraft-like vehicles that rumble over the stark landscape.

Now, one of the town’s tour companies has unveiled the region’s first-ever electric buggy – a vehicle that can move almost silently into areas where the polar bears congregate. The buggy has an estimated range of three days worth of tours and can operate in frigid temperatures.

Frontiers North Adventures, which provided transport to the Guardian and other media outlets to view the vehicle in Churchill, plans to convert the remainder of its fleet over to electric motors, reducing more than 3,600 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions over the next 25 years – the equivalent of 353,635 liters of diesel fuel.

Frontiers North Adventures, which provided transport to the Guardian and other media outlets to view the vehicle in Churchill, plans to convert the remainder of its fleet over to electric motors, reducing more than 3,600 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions over the next 25 years – the equivalent of 353,635 liters of diesel fuel.

The company pitched it as part of a move to address the climate crisis, which experts have long said will have an outsized impact on polar bears.

The company’s maiden voyage for its electric vehicle came as the area remained ice free for the first time in years – a scenario that may prove deadly for the bears.

A handful of kilometers from where the vehicles parked, the dark waters of Hudson Bay lashed at the shore – a rarity for late November and a warning sign for 800 or so polar bears in the region waiting to begin their hunt on sea ice for ringed seals.

In recent years, that wait has grown longer and longer.

While the timing of the ice formation varies from year to year, experts say the trend over recent decades is cause for concern.

That is bad news for the bears, which don’t feed for the months leading up to ice formation. Instead, they laze around the bay, conserving their energy.

“We’re not getting the good years of sea ice formation that we used to have. We’re getting bad years and OK years,” said Andrew Derocher, a professor of biology at the University of Alberta. “When you do that over a long enough period of time, you can expect that your population is going to decline.”

It had been 156 days since most of the bears last ate. At 180 days, starvation begins to set in.

Ice is also breaking up earlier in the season, meaning bears are forced to return to land weeks earlier than normal and have a smaller window for hunting.

Over the last decade, the bears have lost nearly a total of 12 days of ice on either end of the season.

“We’ve always been concerned about an early break-up with a really late freeze-up,” said Derocher. “And that would be the worst-case scenario for polar bears.”

Already, the bears are showing warning signs.

The weight of pregnant polar bears has declined over the years, as have new births. Bears typically lose one kilogram of weight each day they remain on the tundra instead of ice – further adding pressure on the population.

The bear population has dropped by nearly 30% since 1987. If current trends hold, the bears are predicted to undergo a reproductive failure by 2040, accelerating the species’ demise.

“Eventually, you’ll pretty much have like a zombie population of polar bears that just can’t sustain themselves and it’s a matter of time before they’re extirpated. When? That’s the million-dollar question,” Derocher said.

With warming in the north tied to mounting worries over carbon emissions, the longtime Churchill mayor, Michael Spence, has praised the company’s electric vehicle prototype, calling it a vision for “where tourism is going and where our climate is going”.

But the contrast between a futuristic vision of electric vehicles in northern communities and the stark reality of disappearing sea ice, highlights the challenges the region faces.

Churchill once pinned its hopes on a world-class sea port, only to see that vision end in disappointment after the only rail track was washed out by floods. Some in the community of 1,000 hope that the changing climate will enable it to become a major grain port, but much of the town’s economy still relies on tourism . According to government figures, the industry brought in more than C$35m (US$27m) in 2017, mostly related to polar bear safaris.

Manitoba does as much as it can to protect the bears on the ground. Hunting is prohibited, tour vehicles have a narrow set of tracks they can follow to spot the mammals and human-bear interactions, including garbage dumps, have been minimized.

But the late freeze-up is a glimpse at the reality that local operators and scientists are forced to grapple with: the landscape will probably undergo significant changes in the coming years – and polar bear populations will suffer the most.

While other at-risk species can benefit from human intervention – for example fishers in Atlantic Canada are experimenting with rope-less gear to help endangered whales – saving the disappearing sea ice is a far more difficult task.

“There’s no easy fix. We can’t just put a park somewhere. And while it’s a nice idea and indicative of the kind of solutions we need, an electric tundra buggy isn’t going to save the world,” said Derocher. “The only levers that we have left that we can pull are the human behavior ones.”

Leyland Cecco in Churchill, Manitoba