Medical Schools Around the World Are Expanding Their ‘Climate Change Curriculums’

Three years ago, a group of eco-conscious students at Harvard Medical School conducted a poll with their fellow classmates and found that there was strong interest in ramping up climate health education in their courses.

With support from faculty, the Students for Environmental Awareness in Medicine (SEAM) forged a path toward a full “climate change curriculum” for first year medical students at Harvard, which was implemented in 2022.

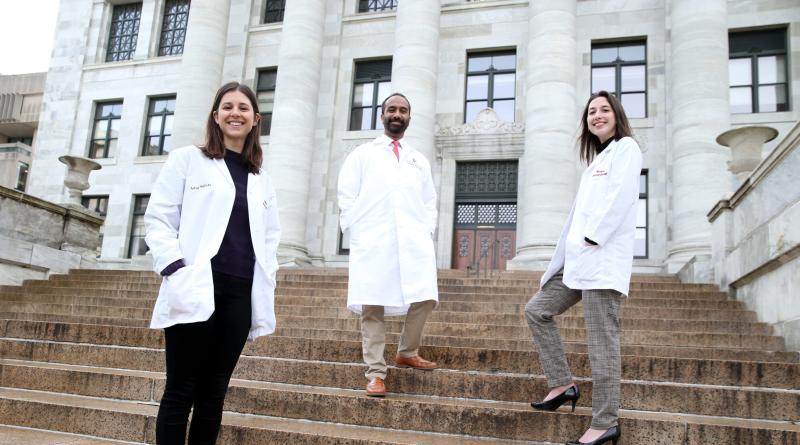

“It really felt like a grassroots effort,” Dr. Julia Malits, a former HMS student who helped lead SEAM’s efforts, told me. She is now an emergency medicine resident at Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s hospitals. “It felt incredibly rewarding to be doing something that I felt so passionate about with a group of students who similarly understood the importance of the health factor impacts of climate change.”

Recent survey data revealed that their efforts may be paying off: Following the first official year of this new climate education push, the majority of Harvard student participants agreed that the curriculum was valuable and improved their understanding of the health impacts of climate change, according to a study published on Wednesday, co-authored by Malits and several other former students and faculty advisors.

This isn’t the only program of its kind. Harvard’s climate curriculum is part of a growing movement in medical schools around the country, and around the world, that have been expanding their efforts to train the next generation of doctors to face climate-fueled health impacts head on.

The Climate-Health Link: Climate change is not just an ecological disaster; it’s a public health crisis, too.

Sometimes, the health impacts of climate change can manifest themselves in obvious ways, like heat stress during a heat wave or injuries after a hurricane. Other times, the effects are more complex, such as the impact of rising seas and salt water ingestion on reproductive health or the changing distributions of insect-borne diseases like malaria in response to increasing global temperatures.

So what does climate health education look like in medical school classrooms? Well, it really depends on the course. For example, in the first year “Immunology in Defense and Disease” course, professors may teach students about how rising temperatures are increasing pollen counts and lengthening growing seasons around the world, which is triggering worse seasonal allergies in patients. In the “Mind, Brain and Behavior” course, students at Harvard are learning about the links between climate change and mental health, which include an uptick in anxiety and depression.

Along with trying to integrate each of the myriad ways climate change is affecting health into medical students’ jam-packed course load, the program focuses on building core competencies to help students learn how to spot climate-related conditions when giving medical care.

“This is not just about teaching climate change, but it’s about good medicine,” Dr. Gaurab Basu, director of education and policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment, told me. Dr. Basu is also a practicing physician and teacher at the medical school, who is leading this initiative from the faculty side.

“If you’re going to be a surgeon or a specialist, primary care doctor, a pediatrician, OB-GYN, whatever it is, this is relevant to [you] no matter what you do,” Basu said.

Climate, Health and Inequity: Through the program, students also learn about the structures and behaviors that have led to the climate crisis—and the inequities that global warming has laid bare in local communities around the world.

Dr. Basu has witnessed these climate and health disparities in his own practice, which is located in Somerville, Massachusetts, but receives many patients from Chelsea, a nearby city with an 80 percent immigrant patient population, he said. Much of Chelsea is located in what’s known as an urban heat island, a phenomenon in which a portion of a city experiences warmer temperatures and a higher risk of heat stress for residents than nearby areas, often due to high amounts of paved areas and a lack of green space.

“We want to have students be able to take care of patients and understand that, you know, their patient lives in certain places, what those environmental exposures could be, but also reflect on why that came to be and speak up,” Basu said. “That’s where the advocacy element comes in. Teaching the students that they are influential in society, and if they’re showing up at city halls [or] if they’re showing up at their state house, they can advocate for policies.”

His philosophy is backed by research; studies show that doctors are some of the most trusted climate communicators in the general public.

A Sea Change For Med Schools: In January 2023, Harvard Medical School approved a climate change curricular theme, creating a mandate that requires content throughout all four years of medical school.

Other medical schools are also weaving climate elements into students’ coursework. Over the past few years, a number of schools, including Stanford Medical School and the University of Colorado School of Medicine, have launched their own initiatives to help train medical students to respond to the health threats from rising temperatures, wildfire smoke, hurricanes and more, reports Mira Cheng for Think Global Health.

In 2019, a group of medical students at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine created the Planetary Health Report Card to evaluate medical schools’ curriculums on the environment and health—a program that has expanded nationally and internationally.

There are still limitations to these types of climate-health initiatives; for example, Basu recognized the need to beef up climate education beyond the first year of medical school, particularly in clinical settings. He said that part of the way to do this is by effectively educating the teachers alongside the students.

“We’re not going to be able to get into every one of those clinics and hospitals,” Basu said. “We have to educate those preceptors—what we call those clinical teachers—so that when they are teaching the students on a more one-to-one kind of mentor kind of level, they’re able to incorporate [climate change] too.”

Malits did not get to take part in the formal climate curriculum at HMS since she was deeper into medical school when it came to fruition. However, since graduating, she has regularly taken climate change conversations outside the classroom—both with her patients and her family. Her mom, who is also a doctor, “didn’t have any training in the health impacts of climate change,” she said. “We have a lot of conversations where I’m explaining to her aspects of healthcare and medicine that she had not been previously aware of, which is really rewarding for both of us.”