‘It seems this heat will take our lives’: Pakistan city fearful after hitting 51C

Residents of Jacobabad say loss of trees and water facilities makes record-breaking temperatures unbearable

Muhammad Akbar, 40, sells dried chickpeas on a wheelbarrow in Jacobabad, and has suffered heatstroke three times in his life.

But now, he says, the heat is getting worse. “In those days there were many trees in the whole city and there was no shortage of water and we had other facilities so we could easily beat the heat. But now there are no trees or other facilities including water, due to which the heat is becoming unbearable. I’m scared that this heat will take our lives in the coming years.”

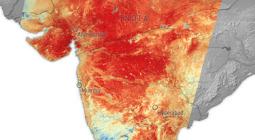

As Pakistan and India sweltered during the recent heatwave, the city of Jacobabad, where Akbar lives, hit a record-breaking 51C. Normally the summer heat starts from the last week of May, but this year, for the first time according to the people here, the heat began in March. Now it will continue till August.

According to the ecologist Nasir Ali Panhwar, author of several books on the environment, the city is particularly badly affected by global heating. This is partly because the city is located in a place where the winter sun comes directly and warms more. Others point out that most of the trees that used to shade the city and the surrounding fields have been cut down and sold, or burned in cooking stoves.

Sardar Sarfaraz, a chief meteorologist of the Pakistan Meteorological Department, told the media that the temperature had already reached 49C in April, a record. He pointed out that Jacobabad “is one of the hottest places in the world” and warned that if the heat began to arrive so early, it was a matter of serious concern.

Akbar says he is worried about the temperature this year. “The heat is increasing every year but the government, including the district administration, is not paying any attention to this serious issue.” Like most of his community, Akbar goes to work early in the morning and works for 12 to 14 hours, earning about 500 rupees (£1.98) a day. He has no choice but to face the heatwave.

Mashooq Ali, the president of the rice mill workers’ union, said that despite the temperatures, “still we have to work because if we do not work, the stove of the house will not work”.

Most workers take two hours off in the afternoon, according to Ali, and then go back to work. “When it gets too hot, we used to sit under the water handpump and use ice water. In the evening when we return home we get extremely tired and want to rest but because of the heat, we do not get enough sleep. Then we go out and sit in an open space so that some air can be felt, but when there is no air, it seems that this heat will take our lives.”

The inhabitants of Jacobabad use hand fans and take frequent baths with cold water from hand pumps. Free cold-water camps have reportedly been set up at four places in the city, and are drawing huge crowds.

Some residents with enough resources move to other parts of the country during these months to escape the heat. According to Huzoor Bakhsh, a journalist who has been reporting in Jacobabad for 20 years, many working-class people move to Quetta in Balochistan, where they work as labourers. He said that because of the deforestation, the intensity of heat had also increased. “Now the people have no way to escape the heatwave and the district administration is inactive in this regard.”

Dr Irshad Ali Sarki, at Jacobabad MS civil hospital, told the Guardian that heatwave wards had been set up to prevent heatstroke, with four or five heatstroke patients admitted and treated daily. Dr Ammad Ullah, another doctor at the hospital, estimates that 50 to 60 people are getting heatstroke every day in this hot season, and said the hospital did not have the capacity to cope. “Some seek treatment from private clinics but the working class do not have the money to get their treatment,” he said.

Citizens complain that, despite the heatwave, the government is not providing drinking water. Donkey carts selling blue plastic cans of water can be seen in large numbers, but there are question marks over the quality of this water.

According to the district administration, the system is complete and water is being supplied through it, but the citizens say the water is polluted and not safe for drinking.

Social activist Mohammad Shaaban is deeply concerned about the rising heat. “We have protested many times for the district administration to take action but no action has been taken yet,” he said. “We fear that in the next few years, Jacobabad will not be able to house humans and animals.”

cover photo: A woman using a paper sheet to fan her child amid a power cut during a heatwave in Jacobabad on 11 May. Photograph: Aamir Qureshi/AFP/Getty Images