I weep for the corals, but what I saw on the Great Barrier Reef gives me hope

From the dry lab on One Tree Island research station – about 100km off the coast from Gladstone and in the southern region of the Great Barrier Reef – I watch a steady procession of scientists walk to their next encounter with what has become the biggest palliative care unit on the planet.

These scientists head out to the reef like doctors heading to a hospital with no control over saving their patients. They head to a hospital where there is no medicine they can administer to alleviate the pain or to make death easier.

Indeed, the greatest living structure on earth is fast becoming the greatest dying structure on earth.

I wonder if you can see that from space?

When I ask why they are doing this work, one of my newly acquired reef science friends quips: “Well it’s not for the money.” Their work as scientists is not about saving or fighting for the reef.

It’s about scientific hope in unprecedented adversity.

It takes extraordinary courage to persist in these circumstances, when powerlessness and despair are deliberately subdued by extraordinary passion and dedication.

To be a reef scientist now, you can’t afford to think like that. It’s too overwhelming, so they look for signs of life, respiration, for coral breath.

Just do your field notes, identify fish, corals, count, record and repeat – lift that, swim there, carry those, descend here and ascend there.

Tears are hard to spot underwater. You can’t feel the churn in a stomach nor the weight on these strong shoulders.

Scientists steer their boats in and out of the lagoon all day, waiting for tides and watching the weather. The work looks important and skilled – dive gear, buckets, equipment, and all with purpose. They talk about sites, about scientific names for fish and coral – of samples and testing – of water temperatures, bleaching, bleached, dead.

As a writer and social scientist, I bring different equipment and ask different questions of the reef and its scientists. Questions that cannot be contained in chambers, counted in transects, collected in water or sediment samples.

I see good people who show up every day – multiple times a day, in fact – and bear witness to a sickness they can record but not treat. It is akin to visiting a loved one in their final days, not because you necessarily want to but because it is the right thing to do.

To be there and do what you can.

I see the human and humanity in these scientists. And it’s as beautiful as any coral I’ve ever seen.

The scientists tell me that the fluorescing coral is quite beautiful, too. The neon blues, purples and yellows sparkle, although they also mention that these colours are like the corals screaming and quite abruptly any skerrick of beauty vanishes.

Everywhere, coral colonies that begin from the ocean floor and stretch towards the light at the surface are fluorescing, dying or dead. I snorkel over these colonies where other marine plants and animals live and I actually “find Nemo” hiding in white tentacles. Today, he’d do well to rethink his escape from the dentist’s tank.

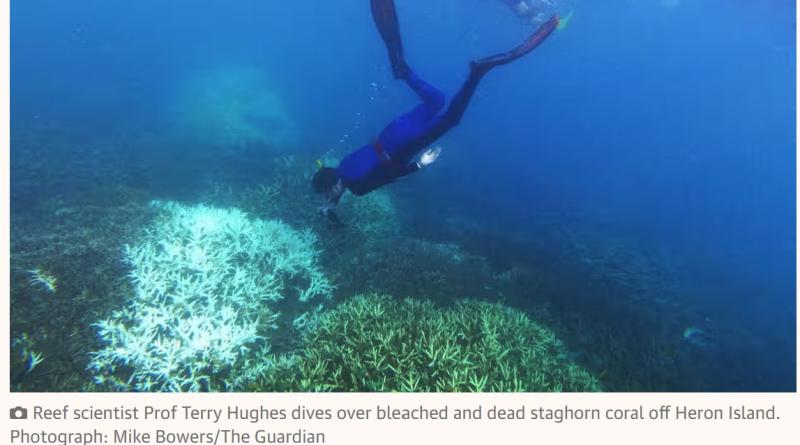

On a visit to nearby Heron Island while I am on One Tree, eminent reef scientist Prof Terry Hughes uses his swear words and describes the bleaching as “fucking awful”.

Before I arrived, I’d checked in with various scouts and they were far more circumspect. “It’s pretty bad,” they’d say. “Pretty bad.” And then the conversation would fade.

So initially I am quite surprised by the amount of marine life I see on my first snorkel down the famed “gutter run” on One Tree Island. The gutter extends from the ocean to the island lagoon, about 300 metres. On a high enough tide you can snorkel with the current, seeing what was once a dizzying array of happy corals, now full of screaming and dead.

I weep for the corals, but I’m buoyed by the marine life. It’s a relief that is short lived.

During our nightly dinner conversations, the reef scientists explain that while there is death, some species are doing quite well. Well, anything that eats algae – the herbivores are at an all-you-can-eat buffet.

But like the short-term buzz of a cruise ship buffet, the food and the feeling of fullness are not going to last. “They don’t know what’s coming,” one scientist says.

On my last days on One Tree Island, the weather turns, winds howl and rain squalls whip those trying to navigate boats through shallow reefs. It’s cold.

The scientists are cold too; wet wetsuits and driving rain remove any delusions of island life and piña coladas.

This quiet band of reef battlers marches across the coral clinkers to another day of exhaustion, physically and mentally.

As I watch them prepare and gear up, I recall their animated descriptions of what it’s like to be at eye level with the fish – not above them, but with them. “You must try it,” they all insist. “You’d love it.”

And I guess this is a metaphor for their connectedness to this reef – to be part of an ecosystem. Not above it, but with it.

When I return home, I vow to get my dive certificate, because whatever it is that I’ve seen in these reef scientists – that courage, passion, humanity – it is beautiful, and I want to be part of it.