How the U.S. Power grid is evolving to handle solar and wind.

As renewable energy sources move mainstream, electricity generation and distribution systems are getting an extreme makeover

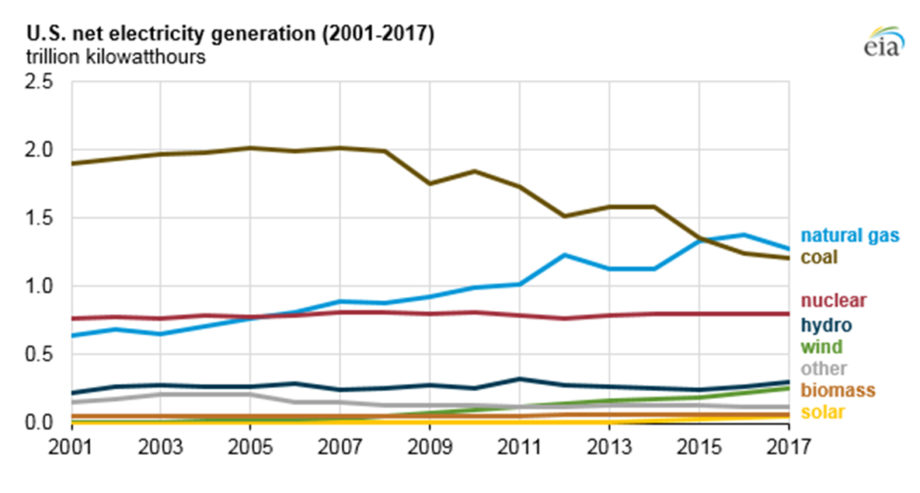

Renewable energy is on the rise. Roughly 15% of the electricity generated in the U.S. comes from renewable sources like wind, solar, geothermal, hydropower and biomass, amounting to 64 million of the 411 million megawatt-hours (MWH) of total electricity generated in July 2019, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. That’s a jump up from just 9 percent a decade ago. From large-scale wind farms to single panels installed on rooftops, renewable energy has gone from novel to commonplace.

This trend has many environmentalists wondering about the future of energy in the U.S. As part of the Ensia Answers project, in which readers suggest topics to be explored in future articles, the growth in renewable energy prompted reader Cynthia Pannucci to submit this question: “Financial support of renewable energy technologies in the U.S. seems strong now. Is our [electric grid] ready to utilize it effectively?”

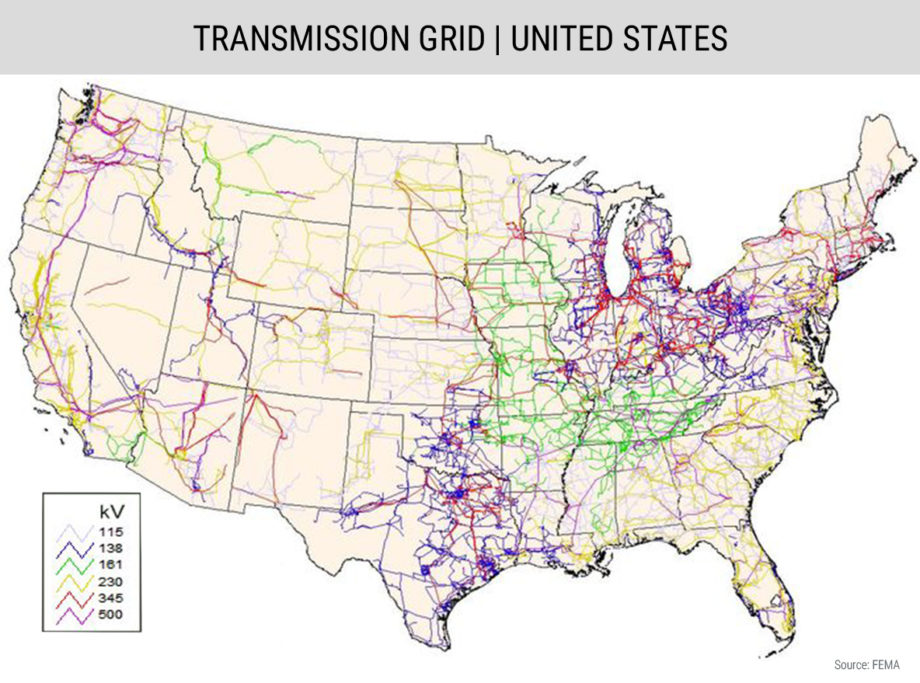

The short answer to this question is no. But as renewables become a larger part of the overall pool of electricity generated in the U.S., the “grid” — the network of electricity generation, high voltage transmission lines, substations and distribution lines that bring power to homes and businesses — is being updated to accommodate it.

Electricity producers and the utility companies that distribute that electricity to households and businesses throughout the country are working to make it easier for renewable sources to provide that power, according to John Jimison, executive director of Americans for a Clean Energy Grid, a non-profit advocacy group focusing on modernizing the grid. “The basis of the transition is the need to get off carbon-based energy and stop emitting greenhouse gases,” Jimison says. “That’s a priority for everybody who understands the science.”

Integrating renewables into the electricity grid has obvious environmental benefits. But upgrading a vast infrastructure made up of thousands of individual utility companies and a web of high-voltage transmission lines is complicated.

The grid was built under a one-way model, in which power is generated at centralized sites and sent through distribution lines to end users. Renewable energy generation facilities— particularly solar and wind — are more widely distributed. Solar and wind farms can feed into the main energy grid, and small-scale installations can be plugged directly into homes. This means that the power coming into the grid from such sources on very sunny or very windy days represents a supply of excess energy that can be redirected through the grid to where it’s needed most. In addition to demand-side management tools like variable pricing for electricity use, new forms of smart grid information technology are being implemented by utility companies to balance out this two-way flow of energy.

Improving the grid to accommodate more renewable energy also means coordinating among utilities in neighboring areas to balance demand and supply, and creating better forecasts of solar and wind output to anticipate generation levels over the course of days, according to Ben York, senior project engineer with the Integration of Distributed Energy Resources program at the Electric Power Research Institute, a nonprofit that conducts research and development on electricity. Implementing these changes, he says, “may also challenge transmission system stability, and system operators need to run detailed simulations to ensure they have sufficient resources available to respond to large events and maintain frequency.”

Increasing the amount of renewable energy in the grid will also require a lot of batteries. Renewable energy sources sometimes generate more electricity than is needed in real time. To maintain a utility’s capacity to provide precisely the right amount of electricity to its customers, large-scale lithium-ion batteries are now being added onto renewable power sites to store that power and distribute it as needed.

These large batteries can hold multiple MWH of electricity; the average American home uses about 10 MWH per year. Getting more renewable energy into the mix of sources powering the U.S. grid will hinge on equipping more utilities and energy producers with such batteries, according to Gregory Wetstone, president and CEO of the Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit American Council on Renewable Energy. He says a key priority moving forward will be to better incentivize the development of energy storage. His organization is part of a coalition calling for the creation of an energy storage investment tax credit as part of the Energy Storage Tax Incentive and Deployment Act of 2019, which was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives earlier this year.

“Over the past four years, more than 77 gigawatts of new renewable power has been added to the grid. With continued modernization of America’s grid, we’ll be able to add significantly more,” Wetstone says. “It’s important to note, however, that there isn’t one unified ‘U.S. grid.’ Moving electricity across the country’s balkanized electrical infrastructure is a challenge, and broader interconnections will allow more renewable energy to get to market.”

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) is exploring how to better integrate the three main grid regions that make up the U.S. energy system. These three systems operate almost entirely independently of one another, with little ability for one to send excess electricity to help meet the demands of another. As part of its Interconnections Seam Study, NREL is working with national labs, universities and industry to develop new ways of sharing a diverse pool of energy sources across these three systems. If successful, this effort could make it easier for abundant wind energy from Texas to power systems in states like Tennessee and Maine, or solar energy from the sunny Southwest to power homes in the cloudy Northwest.

Many believe that the need to transition the grid to better accommodate renewable energy sources will continue for the foreseeable future. “Any change to the resource mix requires careful planning,” says Wetstone, “but we know that a high-penetration renewable grid is feasible through improved transmission and expanded deployment of energy storage and other advanced technologies.”

To answer Ensia reader Pannucci’s original question, the grid is not ready to utilize renewable energy technology just yet. But there’s no reason it shouldn’t be able to — and many reasons to believe it will soon.

ensia