How our responses to climate change and the coronavirus are linked.

- The coronavirus pandemic may lead to a deeper understanding of the ties that bind us on a global scale.

- Well-resourced healthcare systems are essential to protect us from health security threats, including climate change.

- The support to resuscitate the economy after the pandemic should promote health, equity, and environmental protection.

We live in an age in which intersecting crises are being lifted to a global scale, with unseen levels of inequality, environmental degradation and climate destabilization, as well as new surges in populism, conflict, economic uncertainty, and mounting public health threats. All are crises that are slowly tipping the balance, questioning our business-as-usual economic model of the past decades, and requiring us to rethink our next steps.

There are, to a certain degree, parallels that can be drawn between the current COVID-19 pandemic and some of the other contemporary crises our world is facing. All require a global-to-local response and long-term thinking; all need to be guided by science and need to protect the most vulnerable among us; and all require the political will to make fundamental changes when faced with existential risks.

In this sense, the 2020 coronavirus pandemic may lead to a deeper understanding of the ties that bind us all on a global scale and could help us get to grips with the largest public health threat of the century, the climate crisis.

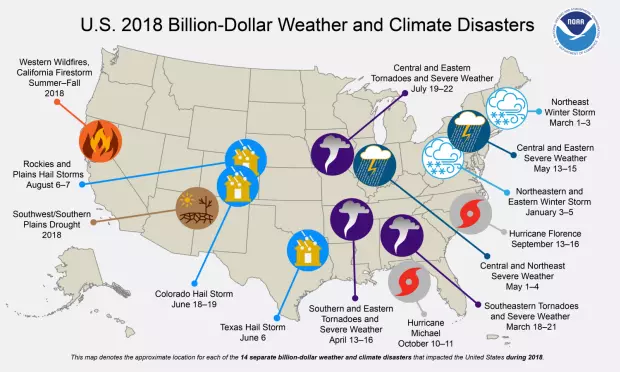

At the World Health Organization (WHO), where I am part of the climate change team, we are seeing the devastating consequences of under-prepared health systems when they are faced with these increasingly regular shocks. Some of these health impacts have a clear climate change signature, such as the increasing frequency and strength of extreme weather events or the expanding range and spread of vector-borne diseases like malaria or dengue. For others, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the connection with climate change is less clear cut.

There is one thing, however, that almost all health shocks have in common: they hit the poorest and the most vulnerable the hardest. They act as poverty multipliers, forcing families into extreme poverty because they have to pay for health care. At least half of the world’s population does not enjoy full coverage for the most basic health services. When health disasters hit – and in a business-as-usual scenario they will do so increasingly – global inequality is sustained and reinforced, and paid for with the lives of the poor and marginalized.

A first lesson we are drawing from the COVID-19 pandemic and how it relates to climate change is that well-resourced, equitable health systems with a strong and supported health workforce are essential to protect us from health security threats, including climate change. The austerity measures that have strained many national health systems over the past decade will have to be reversed if economies and societies are to be resilient and prosperous in an age of change.

For example, the people of Haiti would have been much more adept in coping with and recovering from the lasting effects of 2016’s Hurricane Matthew – which was exacerbated by climate change – if they had had a resilient and well-resourced health system in place to support them. Similarly, many Iranian lives could have been saved at the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak in the country, if its beleaguered healthcare system had been better prepared for what was to come.

Secondly, the ongoing pandemic illustrates how inequality is a major barrier in ensuring the health and wellbeing of people, and how social and economic inequality materializes in unequal access to healthcare systems. For example, the health threat of the novel coronavirus is, on average, greater for cities and people exposed to higher levels of pollution, which are most often people living in poorer areas. The same is true for the health impacts of climate change, with one of its major causes, the burning of fossil fuels, also adding pollution to the air and disproportionately impacting the health of those in poverty.

The WHO estimates that by reducing the environmental and social risk factors people are exposed to, nearly a quarter of the global health burden (measured as loss from sickness, death and financial costs) could be prevented. Creating healthy environments for healthier populations and promoting Universal Health Coverage (UHC) are two of the most effective ways in which we can reduce the long-term health impacts from – and increase our resilience and adaptive capacity to – both the coronavirus pandemic and climate change.

Third, the global health crisis we find ourselves in has forced us to dramatically change our behaviour in order to protect ourselves and those around us, to a degree most of us have never experienced before. This temporary shift of gears could lead to a long-term shift in old behaviours and assumptions, which could lead to a public drive for collective action and effective risk management. Even though climate change presents a slower, more long-term health threat, an equally dramatic and sustained shift in behaviour will be needed to prevent irreversible damage.

Lastly, crises like these offer an opportunity for a regained sense of shared humanity, in which people realize what matters most: the health and safety of their loved ones, and by extension the health and safety of their community, country and fellow global citizens. Both the climate crisis and unfolding pandemic threaten this one thing we all care about.

When we eventually overcome the COVID-19 pandemic, we can hopefully hold on to that sense of shared humanity in order to rebuild our social and economic systems to make them better, more resilient, and compassionate. The financial and social support packages to maintain and eventually resuscitate the global economy post-pandemic should therefore promote health, equity, and environmental protection.

Ultimately, public health is a political choice. A choice we are now confronted with, and one we will have to make over and over again as we transition to a more resilient, zero-carbon, just and healthier future.

Arthur Wyns is a climate change advisor to the World Health Organization (WHO). He writes in a personal capacity, his views do not necessarily represent WHO or any of its member states.

2 April 2020

World Economic Forum