Growing ‘heat blob’ from Atlantic driving sea ice loss in Arctic, study says.

Amount of ocean heat delivered to the Arctic has increased markedly since 2001, according to research

An underwater heat blob from the Atlantic is delivering more and more warmth to the Arctic, causing sea ice to rapidly melt, a study has found.

The research shows that the amount of heat delivered to the Arctic Ocean and the Nordic Seas by ocean currents has increased markedly since 2001.

This influx in ocean heat is likely playing a major role in the warming of the Arctic Ocean and the rapid disappearance of Arctic sea ice, according to the study.

“The most significant achievement of this work is that we have quantified the ocean heat transport robustly for the first time, not only long-term mean, but also its temporal variability,” study lead author Dr Takamasa Tsubouchi, a researcher of ocean circulation at the University of Bergen, Norway, told The Independent.

The research, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, uses ocean temperature data taken across the Arctic from 1993 to 2016.

It is the first to fully quantify changes to how much heat has been delivered to the Arctic Ocean over this time period.

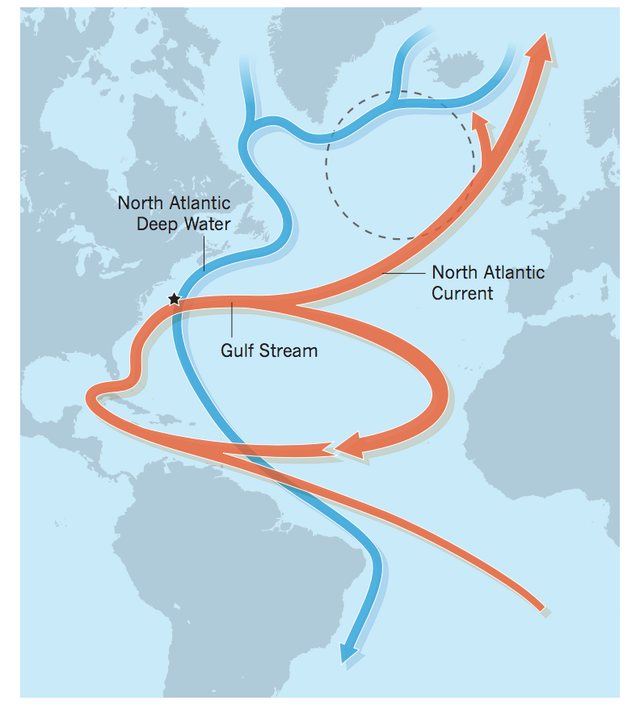

Ocean heat arrives at the high northern latitudes through a vast ocean current, which is known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

The AMOC moves warm, salty water from the tropics to regions further north, such as western Europe.

A diagram of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation

(Praetorius (2018))

It plays a major role in determining the world’s weather. As the AMOC carries warm water northward, it releases heat into the atmosphere. Without this, winters in the UK could be close to 5C colder.

When warm, salty Atlantic water reaches the Arctic, it sinks below the ocean surface to form a “heat blob”. The reason it sinks down is because it is more salty, and thus more dense, than cool and fresh Arctic water.

The sinking of the warm Atlantic water below the cool Arctic water usually allows sea ice to form on top of the Arctic Ocean.

However, the increased delivery of ocean heat from the Atlantic identified in this study could disrupt this balance.

In some parts of the Arctic, such as the Barents Sea, warm salty Atlantic water has begun escaping to the ocean surface, where it is causing Arctic sea ice to melt. This phenomenon is known as “Atlantification”.

Prof Igor Polyakov, a researcher from the University of Alaska Fairbanks who led a research paper in Science documenting Atlantification of the Arctic in 2017, told The Independent: “[The paper] sheds light on our recent finding of Atlantification in the eastern Arctic Ocean which is driven by anomalous influx of Atlantic water into the polar basis and represents a fundamental change of how the polar basin operates.

“Particularly, it provides solid grounds for our arguments for the increasing role of the Arctic Ocean on diminishing sea ice. Thus, I think this an important element of the mosaic painting a complex picture of high-latitude climate change.”

Arctic sea ice reached its second-lowest level on record this September and took much longer than usual to begin refreezing for the winter.

In addition, the last 14 years have seen the 14 lowest levels of Arctic sea ice in the modern satellite record.

Ocean heat is not the only contributor to Arctic sea ice melt. Air temperatures are rising twice as fast in the Arctic than the global average. In some parts of the Arctic, temperature rise is four times higher than the global average.

The new results showing that the AMOC is bringing increasing ocean heat to the Arctic are “puzzling”, says Dr Tsubouchi. This is because previous research has found that human-caused climate change will cause the AMOC to weaken over the 21st century.

To understand the influence of human-caused warming on increasing ocean heat in the Arctic, more measurements will need to be taken, he said, adding: “If we do not measure it, we cannot know what is going on in the ocean.

Funding for this kind of research has declined in recent years.

“There has been no new data collection at all over the last two to three years at least, and we do not know when observations will resume again," he said.

The strength of this study comes from its use of field data, said Dr Michel Tsamados, a sea ice researcher from University College London, who was not involved in the research.

“More observations would result in improved accuracy in the estimates provided here and a better understanding of the ocean and climate system as a whole,” he told The Independent.

23 November 2020

INDEPENDENT