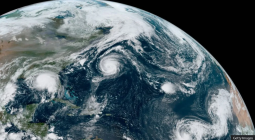

Double punch of hurricanes could become common due to climate crisis

As Floridians prepare to evacuate ahead of Hurricane Milton, debris from Helene still litter swaths of the state

Less than two weeks after Hurricane Helene lashed the Florida coastline, an even more powerful hurricane is hurtling toward the state.

It’s the kind of double hit becoming more common as the climate crisis persists, further complicating hurricane preparation, experts say.

Hurricane Milton strengthened into a dangerous category 5 hurricane on Monday, according to the National Weather Service, and is forecast to batter Florida’s Gulf coast midweek. It’s the third most powerful hurricane in US history, federal officials told reporters on Monday.

The storm could drop 15in of rain on some parts of Florida, with life-threatening storm surges of up to 12ft expected in the city of Tampa. Helene killed a dozen people in the Tampa area.

Millions of Floridians are preparing to evacuate, with mandatory evacuation orders in place across several counties on Monday, including Tampa’s Hillsborough county, and voluntary evacuation orders in place elsewhere.

Swaths of Florida are still lined with piles of broken appliances, smashed furniture and other detritus from Hurricane Helene. Emergency managers are scrambling to deal with the debris before Milton’s strong winds turn it into projectiles and are asking residents to help.

“We’re going to do our best to pick it up. If you do feel that it is going to become a projectile, you can secure that pile. Put it up against a tree, put it behind a fence,” Tim Devin, the Clay county emergency management director, told WJXT television station in Jacksonville.

Ron DeSantis, Florida’s Republican governor, has asked the state’s emergency management and transit divisions to help remove the piles, and some 4,000 national guard troops are also helping with the efforts. The state’s emergency management department is establishing a base camp at Tropicana Field in St Petersburg to support those debris operations.

Back-to-back hurricanes could also strain the Federal Emergency Management Agency (Fema), which has sent over 1,500 personnel to the south-east to help with Helene relief.

In response to swirling misinformation that Fema has drained its budget, the agency has said it has enough funding to address the immediate needs of Helene’s victims, noting Congress recently replenished its disaster recovery fund. Helene could cost upwards of $34bn, according to economic analysis firm Moody’s Analytics.

“We want to assure everyone we have the resources to respond to both Helene and Milton,” Keith Turi, Fema’s acting associate administrator for response and recovery, told reporters on Monday.

Yet the agency’s funding for long-term disaster recovery efforts is running low, federal officials are warning, and Milton could compound that challenge.

Congress is on recess until after election day to place the focus on presidential campaigns, but Joe Biden on Friday warned that he may reconvene lawmakers to approve additional funding.

Storms in quick sequence can also put pressure on personnel levels, whether from local government groups or mutual aid groups, charities and other private aid organizations.

“You’ve got a limited number of people in any one place who can pick up trash, who can fix utilities, who can fix roofs and plumbing,” said Sarah Labowitz, disaster expert and non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “You can deploy people from around the region to help in the recovery, especially if they are not affected as badly. But when you layer on top of that a second storm, the number of people who are out of their homes or without power or childcare goes up.”

Another challenge: managing insurance costs. Estimates show Hurricane Helene caused up to $47.5bn in losses for property owners, and some Florida residents could face additional damage due to Milton.

“Insurance markets already under siege from climate-related disasters are likely to buckle further under the weight of claims from these back-to-back storms,” said Rachel Cleetus, climate and energy policy director at the environmental non-profit Union of Concerned Scientists.

Repeat disasters can also put huge strain on local economies, healthcare systems and social networks. Hurricanes can result in thousands of additional deaths over the coming years, an analysis published in the journal Nature on Wednesday suggests.

As the planet continues to warm, primarily due to emissions from the burning of fossil fuels, back-to-back hurricanes are expected to become more common.

In some areas, including the Gulf coast, such one-two punches could occur as often as once every three years, according to a 2023 article from researchers at Princeton University.

Some regions have already seen multiple disasters in quick succession. In 2008, parts of Louisiana faced Hurricanes Ike and Gustav, and in 2005, many Louisianans were hit by Hurricane Rita shortly after the historically destructive Katrina.

A resident of Houston, Texas, Labowitz has seen these challenges firsthand. This July, Hurricane Beryl pounded the area, just weeks after a powerful derecho. Many as a result endured two power outages in two months, and the psychological toll was also “major”, said Labowitz.

“That kind of back-to-back disaster, it just compounds every aspect of recovery,” she said. “It puts a strain on local resources and equipment and technology and the power grid … and it also puts a real strain on people and communities.”

In preparation for more repeat disasters in the coming years, lawmakers should increase disaster preparedness efforts and invest in improved forecasting, said Cleetus. And boosting climate resilience funding “to keep communities safe ahead of time is also paramount”, she said.

Right now, the primary goal is to “minimize any potential loss of life”, Turi said on Monday’s press call.

“We can rebuild, we can repair, we can deal with the aftermath,” he said. “If we can’t keep people safe in these few days, there’s nothing we can do about it after that.”

Cover photo: By The Guardian