Corporations push “insetting” as new offsetting but report claims it is even worse

More companies claim that supply-chain carbon removal is the way forward. But a new report raises concern over the credibility and transparency of insetting.

For Nestlé, planting millions of trees in and around plantations supplying its coffee is an ideal “net zero” fix.

This – the Swiss giant says – not only captures carbon from the atmosphere, generating credits to be claimed against its climate targets.

But it also protects crops, reduces water reliance and supports workers on the very farms the company sources materials from.

This practice is called insetting, a term creeping into the “net zero” plans of a rising number of corporations.

Instead of buying carbon credits from unrelated third parties – as they would in traditional offsetting schemes – through insetting, companies invest in carbon reduction or removal projects on their own land or the land of their suppliers.

Critical report

Its emergence comes as more doubts are being cast over the reliability of carbon offsets. A new critical report says this is no coincidence.

The New Climate Institute (NCI), a German campaign group, says insetting is simply offsetting in disguise and is plagued by the same integrity issues.

The report also raises concern over companies “successfully” lobbying standards-setters to rubber-stamp the inclusion of insetting claims within their net zero pledges.

In particular, the report points the finger at the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTI), a corporate climate target watchdog supported by NGOs like the World Wildlife Fund and World Resources Institute. The report accuses it of “legitimizing” insetting.

What is insetting?

There is no single and universally-accepted definition of insetting, but the term generally refers to a company offsetting emissions through carbon reduction or removal projects along its own supply chain. Insetting is most commonly used by corporations with a large land footprint and involves protecting nature.

The International Platform for Insetting (IPI) – a business-led group – says insetting brings a more “holistic” approach. “Insetting is an important mechanism for companies not only to achieve their net zero commitments,” Michael Guindon, IPI’s executive director, told Climate Home. “But it also helps companies reach other goals, in improving biodiversity, ecosystems and livelihoods for communities they work with.”

But the NCI claims insetting is just a rebranding operation for “low-standard” offsetting. “The impression is that offsetting has gained a bad reputation, so companies are moving to a different term to avoid criticism, rather than abandoning it altogether,” Silke Mooldijk, co-author of the NCI report, told Climate Home News, “This distracts from the need for real emission reductions”.

The NCI scrutinised the climate pledges of 24 major multinational corporations. It found that the practice of so-called insetting is “gaining momentum and undermining more companies’ climate strategies”.

Offsets – also referred to as carbon credits – have come under increasing criticism over the last few years with academics, journalists and NGOs raising questions over the real contributions to emission reduction. In December 2022 a Guardian investigation claimed up to 90% of forest-based carbon credits approved by a leading certifier are worthless – which the certifier Verra denies.

Methodologies questioned

The NCI report says the insetting claims it analysed are also plagued by a lack of robust methodologies and the required verification steps.

Insetting within a company’s supply chain may take the form of emissions reduction projects or carbon dioxide removals.

The NCI calls both “highly contentious”. It claims that describing emissions reduction projects as insetting is a “false concept”, because this is a measure of reducing its own emissions and should not be used to neutralise some of the companies’ other emission sources. The risk is that reductions may be counted twice.

Carbon dioxide removals include carbon storage in soil or wood. These projects – the NCI says – may be compromised by the same integrity issues as any other offsetting project: the difficulty in demonstrating the emission reductions are additional to what would have happened anyway and that they are permanent.

Unlike offsets, insetting projects do not currently require verification against globally agreed standards.

“This could offer a potential avenue for companies to bypass those standards,” Justin Baker, a forest economist at North Carolina State University, told Climate Home News. “That raises concerns regarding the credibility or potential climate benefit of the insetting action.”

Nestlé and Pepsi

Nestlé and PepsiCo are among the companies relying on insetting for emissions reductions or removals.

Nestlé plans to halve its emissions by 2030 and to reach net zero by 2050. The company says it does not use offsetting outside its value chain to deliver emissions removals – even though some of its brands do buy offsets

Its main focus, it says, is instead on sucking in carbon through restoring forests, wetlands and peatlands on its suppliers’ land.

Climate Home News asked Nestlé to provide detailed information about the company’s projects but did not receive a response.

Nestlé ’s publicly available information on insetting overwhelmingly refers to tree-planting initiatives.

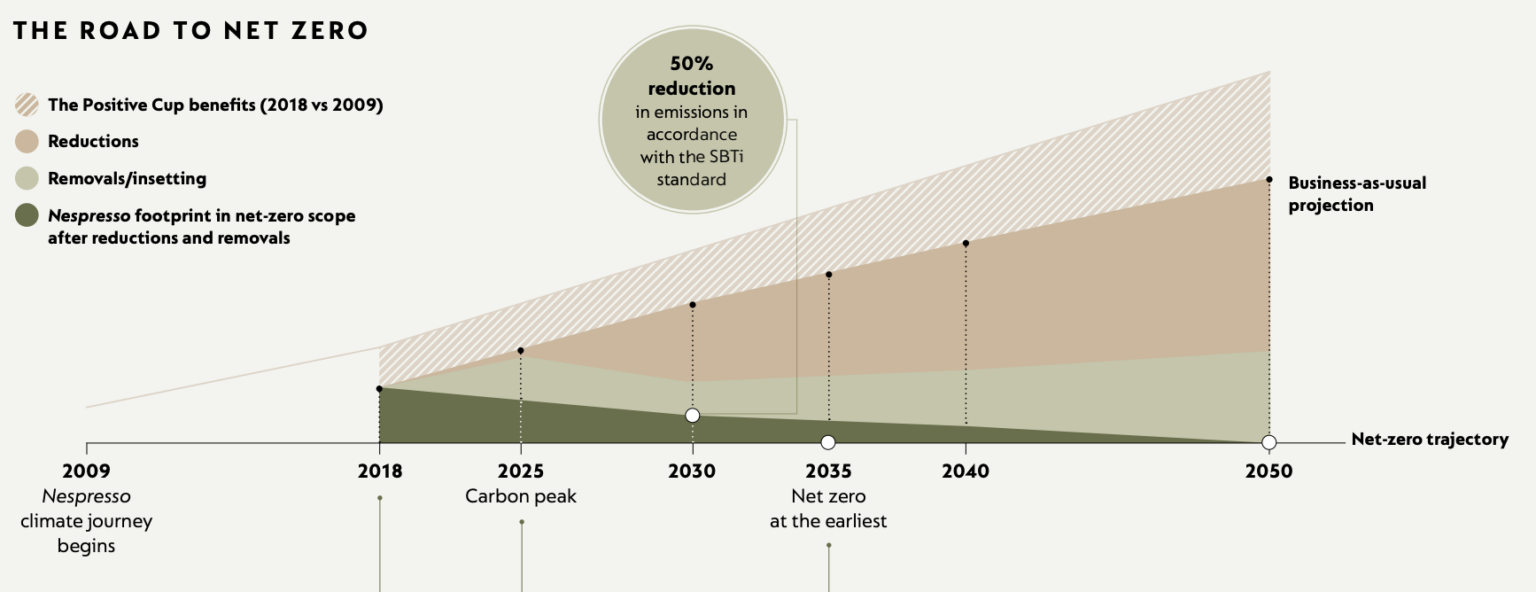

A chart from a Nespresso report shows the role of removals and insetting in the company’s net zero strategy. Credit: Nespresso’s Positive Cup report)

Critics like the NCI say tree planting does not always have permanent benefits. If, for example, trees were cut or went up in flames, the carbon sequestered would be immediately released back into the atmosphere.

A Nestlé spokesperson said that “when it comes to the food and agriculture sector, the NCI approach to decarbonization simply does not work”. “Food and agricultural companies like ours can and must play a role in adopting nature-based solutions to achieve their climate targets,” it added.

PepsiCo aims to reduce emissions by 40% by 2030 and to reach net zero ten years later. In its strategy, the company says it wants to deploy “carbon insetting at scale” without elaborating on specific practices and targets.

In 2021 PepsiCo announced a partnership with the Soil and Water Outcomes Fund to subsidize regenerative agricultural practices on 20,000 acres of land in Illinois, a supply area for the company. They claimed this project would “generate verifiable carbon reductions” that could be used to inset corporate emissions.

“Lobbying to legitimise insetting”

The NCI claims Nestlé and PepsiCo are “among the companies successfully lobbying to legitimise the contentious practice of what they label as insetting”.

Nestlé and PepsiCo are among over a dozen large corporations who provided input into SBTI’s guidance for the forestry, land and agriculture (Flag) sector, alongside experts from several NGOs.

The guidance was supported by the charitable foundation of Intel co-founder Gordon Moore and “additional support was provided” by companies in the Flag sector like furniture shop Ikea and food companies Cargill, Mars and General Mills.

The SBTI is the most prominent standard-setter for corporate climate targets globally. It says its targets are “grounded in an objective scientific evaluation” and represent a more robust approach for companies to manage their emissions.

It treats offsets and insets differently. SBTI’s April 2020 guidance said that “offsets and avoided emissions should not count toward [science-based targets]”.

But, in its September 2022 Flag sector guidance, SBTI accepts removals within a company’s supply chain towards greenhouse gas emission reduction targets.

“No company can purchase offsets to meet its near-term Flag or energy/industry target,” the guidance says, “only removals on land owned or operated by a company or within a company’s supply chain can be included”.

In a separate document, the group said it would “assess insetting on a case-by-case basis during the validation process” due to the absence of a “standardization of the term”.

Climate Home News asked SBTI to provide details on the number of insetting claims approved or declined, but received no response.

An SBTi spokesperson told Climate Home News that “carbon credits may be used between producers and buyers as evidence that a reduction or removal occurred in association with a commodity to ensure unique claim to the [greenhouse gas] reductions or removals”. It added that “this only applies for Flag if such a reduction or removal is associated with on-farm actions that sit within company value chains”.

photo credit: Companies claim trees planted on coffee farms as part of insetting projects can help crops. Photo: USAID Biodiversity & Forestry