Climate science is supporting lawsuits that could help save the world.

Governments have failed to slow climate change quickly enough, so activists are using courts to compel countries and companies to act — increasingly with help from forefront science.

Friederike Otto hadn’t really thought much about the legal world when she answered the phone one day in 2018. On the other end of the line was Petra Minnerop, a scholar of international law at the University of Durham, UK, who was exploring how the legal system might help to save the planet.

Minnerop had developed an interest in climate litigation — efforts to hold governments and companies legally responsible for contributing to global warming. Following the success of several climate lawsuits, she was seeking to get involved and thought Otto’s research might help. Otto, a climate modeller at the University of Oxford, UK, is one of the world’s leaders in attribution science — a field that has developed tools to assess how much human activities drive extreme weather events, including the heatwaves, fires and floods that have ravaged parts of the globe this year. In their telephone call, the pair realized that they had similar aims and they set about thinking how science and environmental law might trigger more action to limit climate change.

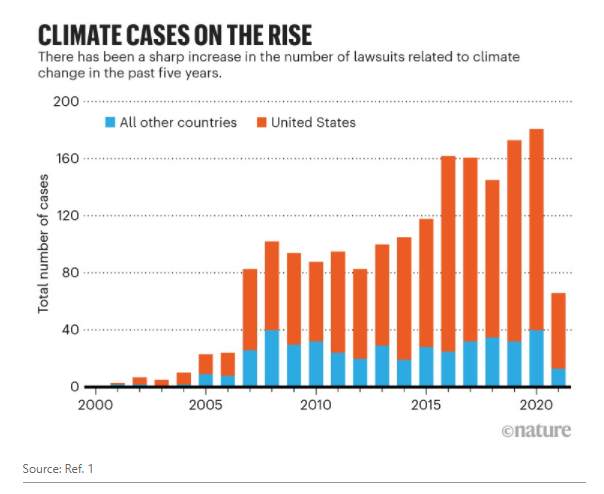

Minnerop and Otto are in the vanguard of scientists and legal scholars who are assisting in lawsuits to force governments and companies to take action against climate change. Over the past few decades, environmental groups and citizens around the world have filed more than 1,800 climate suits. Science has been central to supporting the arguments in these cases, but the vast majority have relied on the most basic conclusions of climate research. Now, Otto, Minnerop and others are seeking to bring in the latest science to improve lawsuits’ chances of driving substantial reductions in greenhouse-gas pollution.

“There’s a really big gap in many cases between what can be said scientifically and what is brought to courts,” says Otto.

Court order

The number of climate suits has surged in recent years, thanks in part to a growing youth climate movement that has injected fresh energy into activism aimed at protecting the planet. Since 2015, plaintiffs, including children, have filed more than 1,000 climate cases, according to an analysis1 published in July by researchers at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment in London (see ‘Climate cases on the rise’). In 37 cases, lawsuits allege that governments have not lived up to their promises to lower the risks of climate change or to set goals that are ambitious enough. These cases, which target systemic problems, have generated the most attention, and could have some of the most far-reaching consequences if they are successful. Other cases focus on specific projects or practices, such as coal mining in Australia or deforestation in Brazil.

Success at court was limited at first. But a string of wins in the past two years is raising hopes that the legal scales are tilting in favour of stronger climate action. In May, the District Court of The Hague ruled that the energy company Royal Dutch Shell must reduce its carbon emissions by 45% compared with 2019 levels over the next 9 years, arguing that the high level of current emissions by the group might contribute to imminent environmental harm to Dutch citizens.

A month earlier, the Federal Constitutional Court in Germany ordered the government to lay out a clearer strategy towards achieving its climate targets for the period after 2030. The country is the world’s seventh-largest greenhouse-gas emitter. A similar court ruling last year compels the Irish government to flesh out its climate mitigation plan and explain how it intends to meet the goal of cutting emissions by 80% by 2050, relative to 1990 levels.

These two cases follow a precedent set by a landmark decision in 2015 in the Netherlands — a few months before nations agreed in Paris to limit global warming to well below 2 °C relative to pre-industrial levels, and preferably to 1.5 °C. The lawsuit had been filed in 2013 on behalf of almost 900 plaintiffs, including children. The court ordered the Dutch government to take action to lower domestic greenhouse-gas emissions by at least 25% by the end of 2020, compared with 1990 levels.

“People said we would have zero chance of winning,” says Jan Rotmans, a climate scientist at the Dutch Research Institute For Transitions in Rotterdam, who set up the Urgenda Foundation that filed the lawsuit. “But it turned out we were a catalyst.”

A court of appeal and the Supreme Court of the Netherlands later upheld the ruling. Emissions in the Netherlands in 2020 were down by around 24%, but missed the target; the Urgenda Foundation announced in June, after a meeting with Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, that it is considering suing the government for damages resulting from insufficient climate action.

Similarly to subsequent rulings, the Dutch court’s move was heavily based on the body of climate science compiled by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In its judgment, the court cited scientific consensus that a global atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide that was higher than 430 parts per million — the threshold to 1.5 °C warming — would mean “a serious degree of danger” for Dutch citizens, including extreme heat, drought, precipitation and sea-level rise.

“For the first time, a court had recognized that a government violates its duty of care for citizens if it doesn’t do enough to curb emissions,” says Joana Setzer, who specializes in climate litigation at the Grantham Institute and is a co-author of the July report. “This meant a lot from a legal point of view.”

Other cases have tended to follow the same scientific justification. Referring to IPCC science, judges in Ireland and Germany acknowledged that insufficient climate action might soon lead to disruptions — including wild weather or dangerous sea-level rises that would threaten the livelihood of future generations. In South Korea, a group of young people are challenging their government for human-rights violation on the same grounds. Judgments in that case and similar ones in the United States are still pending.

As signs of dangerous climate change are becoming more evident, pressure is mounting to hold governments and major carbon-emitting firms accountable. And this year has brought a string of weather extremes, including record heat in July in parts of North America, wildfires raging in Siberia and severe rainfall and floods in Belgium, Germany and China. Studies by Otto’s group and others have already demonstrated that climate change is at least partly responsible for the North American heatwave and the central European floods. Extreme weather events worldwide will become increasingly severe as temperatures continue to rise, the IPCC said in August, in the first part of its latest assessment of the state of climate science2.

Bigger picture

The new IPCC reports will add pressure for stronger climate action, but as climate litigation expands in scope, it will draw on a broader range of research, says Peter Frumhoff, chief climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“It’s a benefit to have the IPCC as a framework of accepted climate research,” he says. “But IPCC science isn’t all you need at court. There’s a lot more to the picture.” Future liability cases, says Frumhoff, could also incorporate the results of emerging attribution science, reviews of countries’ compliance with national commitments to the Paris agreement and studies related to what companies are doing in terms of the climate risks of their products.

There’s another reason that lawsuits might start to rely more on science that goes beyond what appears in IPCC reports. Those massive studies take years to compile, so the results can be out of date by the time the reports are released. Before this year, the last major IPCC report on the physical basis of climate science was published in 2013. Climate-change attribution was described as ‘challenging’ in a 2012 IPCC special report on managing the risks of extreme events and disasters3; but that science has matured to the point at which Otto and other researchers conduct attribution studies within days to weeks after major weather anomalies.

Yet judges are still reluctant to grant legal weight to attribution studies. A joint study by Minnerop, Otto and their colleagues, published in June4, found that such results are scarcely cited in climate lawsuits because of lingering doubts over the robustness of the findings. The IPCC’s latest report highlights that the methodology of climate-change attribution has matured since the last assessment, and that the results of state-of-the-art studies can now be considered robust.

This kind of statement by the IPCC in support of attribution science could make a difference, legally, as scientists and legal scholars start working together more. It will get harder for courts to ignore the relevant science that gets brought forward, including new work, says Frumhoff. The Union of Concerned Scientists created a virtual rendezvous point last year for scientists and legal experts who might want to team up. The hub, which provides legal scholars, lawyers and local officials with access to a broad range of science relevant in climate litigation, aims to catalyse legally relevant research across disciplines and make it easier for lawyers and legal scholars to use science in their cases.

One particularly relevant field is source attribution, a growing branch of attribution science that seeks to identify the relative contributions that different economic sectors and activities have made to climate change. For example, a 2020 assessment of the plastic industry’s contribution to greenhouse gases found that the sector’s emissions up to 2050 could total roughly 10–13% of what can be emitted if the world hopes to stay below 1.5 °C of warming5. Such studies could help courts considering lawsuits that allege that government agencies or companies have failed to prepare for the effects of climate change, or have contributed to it and should be held accountable.

“Causality is a key aspect in climate cases,” says Minnerop. “Any science that might convince judges that greenhouse-gas emitters are liable for their actions or inaction could be a game changer.”

Claiming financial damages from individual emitters might be tricky, however. “It is hard to see a judge accepting a damage claim and telling a company to pay compensation on the basis of source attribution,” she says. “It would open a flood gate.”

In the case against Royal Dutch Shell — and in climate suits against governments — plaintiffs chose a different strategy. Those lawsuits focus on getting them to take responsibility for mitigating looming climate risks, rather than seeking compensation for harm suffered already.

A crucial piece of evidence in the Shell case was a set of expert reports on fossil-fuel economics, filed by the Dutch climate-action group Milieudefensie. During the case, Shell’s lawyers had argued that if the company were to reduce its production of oil and gas, other firms would increase theirs, so that global production would remain the same. Milieudefensie asked Peter Erickson, the climate policy programme director at the Stockholm Environment Institute in Seattle, Washington, to respond to that substitution argument. The court agreed with Erickson that a reduction by Shell would not result in other firms making up the entire difference.

Expert opinion

Other science relevant to climate lawsuits includes studies about how climate change causes health problems; work that tracks environmental damage using satellite observations; and analyses of how financial flows from one country can increase fossil-fuel pollution in others.

“Too many environmental permits are given by local officials without adequately considering climate,” says Erickson. “I’m happy for my scholarship and science to be used where it is helpful. But it needs many more experts summarizing for courts the science in a clear and strong way.”

For all that, courts still tend to rely most on the scientific conclusions of the IPCC, says James Hansen, a climate scientist at Columbia University in New York who has advised or served as an expert witness in dozens of climate lawsuits since 2005. Hansen is currently both a plaintiff and a witness in the case of Juliana v. United States, which 21 young people brought forward in 2015 against the US federal government, demanding stronger emission cuts to help the world stay below 1.5 °C of global warming.

“As an expert witness I found the case to be frustrating,” Hansen says. “I spent months at a time preparing an expert report on climate change only to see all that work buried in court proceedings and hardly considered by the judges.”

A US court dismissed the original claim in January 2020, but the plaintiffs filed a motion this March to amend their suit and a judge ordered the United States and the plaintiffs to explore a settlement. Talks are ongoing and Hansen hopes that a settlement will include support from the Biden administration for a US carbon fee or tax.

Legal scholars foresee a range of other climate-related lawsuits coming up. One type could target financial entities that contribute to future climate change, such as companies trading in goods that can be linked to deforestation. These cases will rely on analyses of global trade and financial flows, says Setzer. Other types of lawsuit could involve ‘greenwashing’ — dubious claims that consumer products are environmentally friendly — and companies’ fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of business partners, she says. Research on whether countries meet their national contributions to the Paris agreement, and analysis of the costs of inaction, will also become increasingly relevant for future climate lawsuits, she adds.

Meanwhile, efforts are under way to support affected communities in poorer countries. ClientEarth, an international group of environmental lawyers, supports people affected by landslides in the Bududa district of Uganda who took the country’s government to court for failing to protect local villagers from climate risks. ClientEarth is also training lawyers and public prosecutors in China with a view to bringing companies to court for polluting the air. If successful, such efforts could help to limit climate change because some air pollutants contribute to global warming. But it is unlikely in China’s autocratic political system that a court would challenge the government for its climate policies, says Setzer.

Still, recent wins inspire hope that courts could help to tackle a planetary crisis — one that governments’ legislative and executive branches have so far failed to avert. “The judiciary is less subject to political haggling and horse trade,” says Hansen. “Court victories against governments are forcing them to think about and work on actual actions rather than promises for the distant future.”

But law on its own won’t be enough, cautions Rotmans. “Courts cannot force the global energy transition needed to stabilize the climate,” he says. “Winning a lawsuit is one thing; getting rid of fossil fuels is another.”

Nature 597, 169-171 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02424-7

8 September 2021

nature