Climate policy and action: Citizens at the forefront.

Both the climate crisis and the Paris Agreement are pressing policymakers for effective and sustainable climate action. Still, results show that our progress towards goals agreed is not as fast nor efficient as it should be. Dr Haris Doukas, Associate Professor in energy policy and management at the School of Electrical & Computer Engineering of the National Technical University of Athens, has proposed a holistic framework where the public and other stakeholders are actively involved in modelling science and policymaking.

From climate change, sustainability, and the Paris Agreement to the current pandemic, our life has been severely impacted by our choices. Changes that were scarcely noticed a few decades ago are now more noticeable than ever, with the climate crisis and the pandemic being in the centre of attention. Over the years, scientists, policy advisors, and governmental representatives have tried to create policies and guidelines that can put climate crisis under control, promote sustainable development, and control energy management. The Paris Agreement puts pressure on countries to deliver specific outcomes over a specified period of time, but results show that it is rather difficult to achieve them. The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced unprecedented issues, making 2020 a less-than-ideal year, not only towards the fulfilment of the goals set through the Paris Agreement and other climate policies but also for the continuation of life as we know it.

Climate policy modelling

Over the past decades, there has been a significant focus on the – then upcoming, now established – climate crisis, with development of models, introduction of policies, and establishment of guidelines trying to predict the future and protect the environment and living standards. The majority of people today are familiar with terminologies such as the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement, Nationally Determined Contributions, or the more recent EU Green Deal, and most people have in one way or another become aware of or experienced the effects of the climate crisis.

A tremendous amount of work is needed to develop such models and policies. More so, ongoing interdisciplinary collaboration is required, with input from several science and engineering sectors using results from experimental activities and simulations. Starting from the greenhouse effect and the rise of temperature, moving to the need for sustainability and sustainable development and, more recently, the energy crisis and the need for energy management, currently developed models and policies can combine essential aspects and insights into all these areas, or offer a more detailed approach to a targeted theme. In the first case, we are talking about Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), which have offered great help towards climate policymaking. However, these models have also been heavily criticised due to their scientific modelling core that does not allow policymakers to intervene with model construction, and due to their inability of effectively capturing the entire spectrum of uncertainty associated with this research area.

Policymaking flaws

Despite the efforts of scientists and policymakers to collaborate and produce applicable guidelines that will help tackle the climate crisis, the actual implementation of those models and policies in real life is effectively lacking. A good example to illustrate this issue are the good-old recycling schemes, with urban legends around the way they operate and whether recycling is taking place to the degree needed to show results that actually make a difference. Another example, close to many of us at this point, is the use of face coverings in public spaces, or the rules about mixing of different households in light of the effect of these factors to the spreading of coronavirus. Both examples illustrate perfect policies on paper, but do not seem so great when implemented.

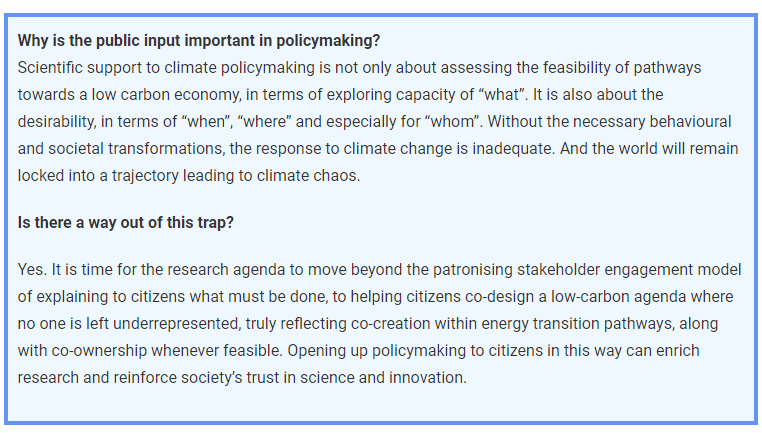

The reason behind this discrepancy is simultaneously simple and complicated. It lies in the absence of the citizens’ view during the policymaking process, the absence of the view of governments or industrial stakeholders in the guidelines decided from policymakers, and the absence of the opinion of unions, associations, non-governmental organisations, and other civil society organisations during the policymaking process.

One might argue that citizens, or any of the other stakeholders, have no reason to participate in policymaking, especially when it is governed by scientific processes and models built around carefully collected and analysed data through extremely difficult-to-memorise techniques. However, citizens are those that will have to follow the guidelines imposed by the policy, and eventually be instrumental towards the achievement of the goal that the policy is set out to achieve. Similarly, governments, unions, and associations are those principally that will have to impose the new rules, make them implementable for the public, and assess their correct implementation. Furthermore, industrial stakeholders will most probably be affected from new policies, so they should have a say, too.

All stakeholders at the forefront of policymaking

The idea of including the say of all actors in policymaking was highlighted by Dr Haris Doukas, an Associate Professor in energy policy and management at the School of Electrical & Computer Engineering of the National Technical University of Athens. His area of expertise is the development of decision support systems for integrative energy and climate policy, placing the human factor at the core of the modelling processes towards energy management and sustainable development. Including all relevant stakeholders, past the ‘usual’ suspects (i.e. scientists), in the policy and model making process, Dr Doukas’ ambition is to derive policies that are implementable in real life, not just on paper.

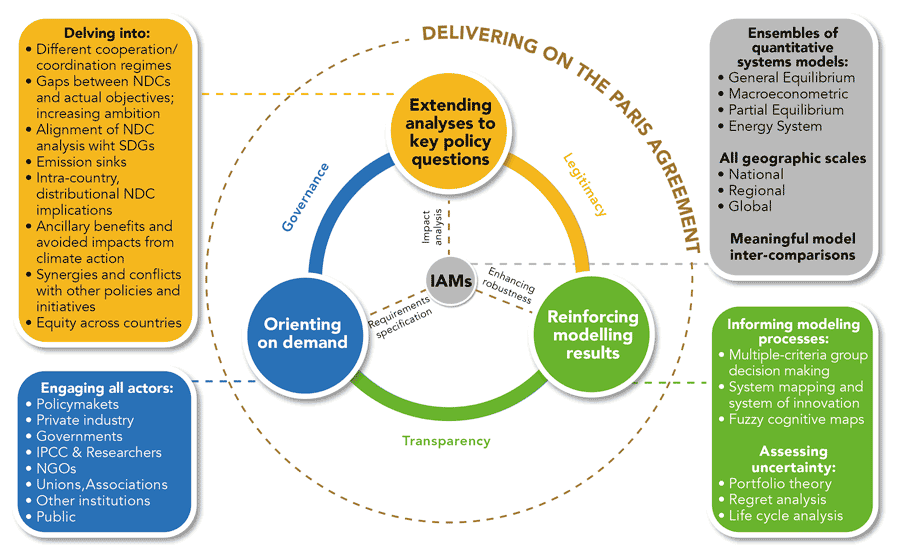

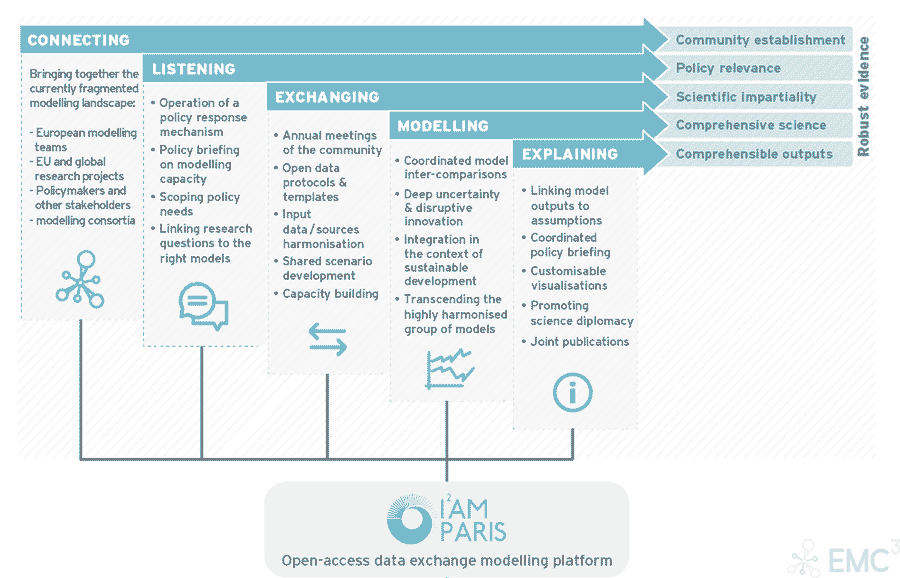

Having identified the gap between the representation of the needed actions (or rather, the final goals), and the realistic application and stakeholder response to that representation, his colleagues and he proposed a diverse, robust framework that could actively help achieve the deliverables set from the Paris Agreement. His proposal includes input from all stakeholders of policymaking and implementation, promoting transparency, legitimacy, and robustness of the modelling tools and obtained results. In their recent publication, Dr Doukas and his team described the proposed framework, suggesting a plethora of policy and decision support tools based on multiple criteria, such as stochastic uncertainty, mapping and exploitation of stakeholder knowledge, and multi-model settings, rather than the ‘traditional’ approaches used currently. Such decision support tools can be used in an effort to integrate the existing, disconnected policymaking framework with the actual abilities and needs of the society it is aimed at.

The use of linguistic variables in policymaking

Yes, you read that correctly. According to previous published work of Dr Doukas, the next generation of variables that should be taken into consideration during policymaking are not based on hard numbers. Instead, efforts to capture the human element of policy design and implementation must be made. Under few circumstances will citizens and other stakeholders be in a position to provide scientifically meaningful input, e.g. for theoretical modelling and foresight analysis, in the form of numerical values that models run on. More often than not, their tacit knowledge will be expressed in other types of variables, like natural language. Such variables can help understand and control underlying uncertainties, making sense of important factors that cannot be described numerically, but should be taken into consideration for a holistic approach towards climate policy that can successfully lead towards achievement of the Paris Agreement goals. Especially in the era we live in, with the effect the pandemic had and will further have on the climate crisis and existing and future progress of attempts for energy management and sustainable development, creating policies that listen to “what people want” and “what people can do” is fundamental for their success. Towards this goal, using decision support tools based on the incorporation of linguistic variables and computing with words can offer a great way of capturing the essence of human behaviour from the various stakeholders. Such linguistic variables can be a set of words ranging from “none” to “medium” to “perfect”, capturing the opinion of various stakeholders, and moving closer to the cognitive way that we, humans, perceive uncertainty. In a recently published review, Dr Doukas elaborated on the potential of using linguistic variables in supporting climate policy, aiming to bridge the gap between policymakers, reasoning behind policymaking, representation, and computing of “unorthodox” variables.

The future of climate policy and sustainable development

The climate crisis is undeniably real and will massively affect all of us and life as we know it. Despite the efforts of the scientific community to act, prevent, and reverse the existing situation, results show that policy lags or delays exploit scientific findings, and that the response of the public to proposed policies is not always aligned with the best-case scenario. The added level of difficulty introduced by COVID-19 means that we need to do more – “we”, as in the policymakers, scientists, public, governments, and various other stakeholders. In order to achieve the goals set by the Paris Agreement and the more recent EU Green Deal, citizens need to follow policy implementation and lead the envisaged transitions. For that to happen, policies need to be adapted to a stakeholder-approved, implementable level, rather than being based solely on scientific calculations or political ambition. Policies with consensus from all stakeholders can lead to mutually beneficial actions, allowing to tackle multiple “crises” at a time, as is the case today. Supporting a citizen-led transition in policymaking could pave the way towards the humanisation of the process, and the introduction of diversity, both in opinions and in tools used, leading to game-changing results.

References

- Doukas, H., Nikas, A. (2020). Decision support models in climate policy. European Journal of Operational Research 280 (1), 1–24.

- Doukas, H., Nikas, A., Stamtsis, A., Tsipouridis, I. (2020). The Green Versus Green Trap and a Way Forward. Energies, 13(20), 5473.

- Doukas, H., Flamos, A., Lieu, J. (ed.) (2019): Understanding risks and uncertainties in energy and climate policy: Multidisciplinary methods and tools for a low carbon society, ISBN 978-3-030-03152-7, Springer Open, Cham. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03152-7

- Doukas, H., Nikas, A., González-Eguino, M., Arto, I., & Anger-Kraavi, A. (2018). From integrated to integrative: Delivering on the Paris Agreement. Sustainability, 10(7), 2299.

- Doukas, H., (2013). Modelling of linguistic variables in multicriteria energy policy support. European Journal of Operational Research, 227 (2), 227–238.

1 December 2020

Research Features