Climate crisis: what can trees really do for us?

By the power of sunlight, forests turn huge amounts of carbon in the air into food: sugars for themselves and leaves, bark and roots that feed animals and microbes. Respiration, which happens in the cells of all living things in the forest, releases energy from that food and carbon dioxide (CO₂) back into the air.

As the amount of carbon in the atmosphere rises, this eat-and-be-eaten cycle increases to keep up. Metabolically, trees are running just to stand still. In the course of all this cycling, forests are locking up the major part of the 33% of human-caused emissions removed from the atmosphere into the land each year.

I (Rob) work in a forest full of beautiful 175-year-old oaks. Global CO₂ levels were around 280 parts per million (ppm) when these trees were seedlings. Now global atmospheric concentrations exceed 415ppm and are rising rapidly. Should these oaks reach 200 years old (not old for an oak), they will be surrounded by air containing around 550ppm of CO₂. Can the world’s mature forests stand these changing conditions and continue to offset some of our emissions from burning fossil fuels?

Carbon current accounts

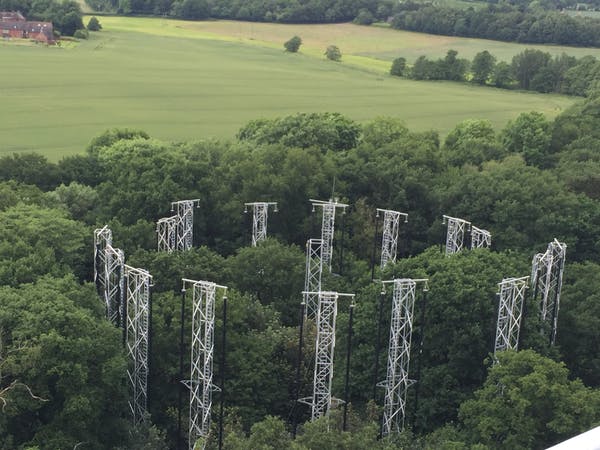

To find out, my colleagues and I at the University of Birmingham’s Institute of Forest Research use a free-air CO₂ enrichment facility. Imagine a dinosaur-free Jurassic park with 102, 25 metre-tall towers treating forest patches with CO₂-enriched air that replicates the mid-century atmosphere: 565ppm – 150ppm above present levels. Then we measure everything we can: the width of tree stems, the size, weight, and chemical make-up of leaves, the branching architecture of the roots and much, much more. In this way, we record changes in the forest’s manufacturing of stuff, and in its health.

Our first results are in. In the canopy, photosynthesis rates are up to a third higher on sunny summer days in the CO₂-rich patches. Over a growing season, the increase is about a fifth. These are big numbers: imagine if your annual income went up by a fifth. Photosynthesis is the forest’s carbon income.

Since we began this experiment in 2017, the forest patches exposed to higher CO₂ appear healthy and productive. That may seem unsurprising. After all, plants love CO₂ so much that farmers add it to greenhouses to supercharge fruit and veg growth.

But forests are not nurtured. They have to fend for themselves, winning (with their fungal partners) all the nutrients they need to balance any CO₂ bonanza from the earth on which they stand. Extra CO₂ photosynthesised into sugar can be too much of a good thing, like an imbalance in our diet.

Think of forests as carbon current accounts, bringing carbon in through photosynthesis and spending it on all the energy-giving respiration that keeps everything in the forest alive. In a healthy and productive forest, a little more comes in than goes out of the current account at the end of every year.

Forest carbon current accounts can hold carbon for decades, occasionally centuries, in their standing timber and roots and soil, tiding us over the 21st-century peak in atmospheric CO₂ – a carbon cashflow crisis caused by burning fossil fuels and deforestation.

Well-managed forests can yield timber and fuel while reducing carbon in the atmosphere. But carbon savings accounts, which put the stuff away for millennia – by pumping it into reservoirs deep underground, for example – are also needed.

People and trees

Scientific models have estimated how much tree planting or reforestation is needed to offset rising CO₂ in the atmosphere. As with most efforts to translate theory into action, the real-world experiences of actually doing this are often very messy indeed.

How reforestation campaigns are funded and tree planting incentivised will determine where and which kinds of trees are planted. How the land is ultimately governed will also decide how long new trees survive. International efforts to grow the planet’s tree cover show how difficult these barriers can be to overcome.

A recent study in northern India found that decades of expensive tree planting programmes had not increased total canopy cover. And the planted areas did not offer any major benefit to local people, like new food or firewood. This was because new trees couldn’t be planted on nearby farmland, and so were instead added to areas that already had some tree cover, reducing the potential carbon savings of the whole endeavour. Local foresters were also preoccupied with meeting tree planting targets, rather than nurturing the kinds of forests and trees which local people valued.

Land is never just about carbon. Trees and forests shape microclimates and water cycles, support biodiversity and provide food, building materials and medicines to local people. They also have different cultural and spiritual values depending on where you are in the world. Forests are often nestled within landscapes occupied by all sorts of other uses, like farms and towns and cities.

Everyone has different preferences for how landscapes should look, and whose vision wins out depends on relationships of power. Researchers working in Uganda in 2014 described what they called carbon colonialism: plantations established to offset greenhouse gas emissions destroyed the crops and burial sites of local people and convicted those accused of trespassing on what had previously been public land. This is just one among many examples of tree planting, however well-intended, blighting lives.

Using trees as a tool becomes unjust when it involves asking poorer rural people to compromise their livelihoods so that wealthier people or nations can continue to consume fossil fuels. Rather than asking if trees can help tackle the climate crisis, perhaps we should ask how much the world should really rely on trees as a climate solution.

There is a lot to be learned from efforts that have managed to increase tree cover and offer benefits to local people, like new income sources. Often, these initiatives are successful because they take local needs and values seriously. Local and indigenous people are leaders in this process, not afterthoughts. And ultimately, reforestation will succeed if it benefits people, as well as the planet.

12 October 2021

THE CONVERSATION