Climate change: What's it like living in a place where it's 50C?

The climate crisis is no longer a future concern. In many parts of the world, it has already begun.

Millions of people are living with extreme temperatures, facing a growing threat of flooding or wildfires. Here, five people explain how extreme temperatures have changed their lives.

'We have many sleepless nights'

Shakeela Bano often lays out her family's bedding on the roof of their one-storey house in India. Some nights it's too hot to sleep indoors. The roof can be too hot to walk on. "It's very difficult," she says. "We have many sleepless nights."

Shakeela lives with her husband, daughter and three grandchildren in a windowless room in Ahmedabad. They have only a single ceiling fan to keep them cool.

Climate change means many cities in India are now hitting 50C. Densely populated, built-up areas are particularly affected by something known as the urban heat island effect. Materials like concrete trap and radiate heat, pushing temperatures higher. And there's no respite at night, when it can actually get hotter.

In homes like Shakeela's, temperatures now reach 46C. She gets dizzy in the heat. Her grandchildren suffer from rashes, heat exhaustion and diarrhoea.

Traditional methods for staying cool, like drinking buttermilk and lemon water, no longer work. Instead they've borrowed money to paint the roof of their home white. White surfaces reflect more sunlight and a coat of white paint to the roof can bring down temperatures inside by 3-4 degrees.

For Shakeela, the difference is huge; the room is cooler and the children sleep better. "He would not sleep through the afternoon," she says, pointing to her sleeping grandson. "Now he can drift off peacefully."

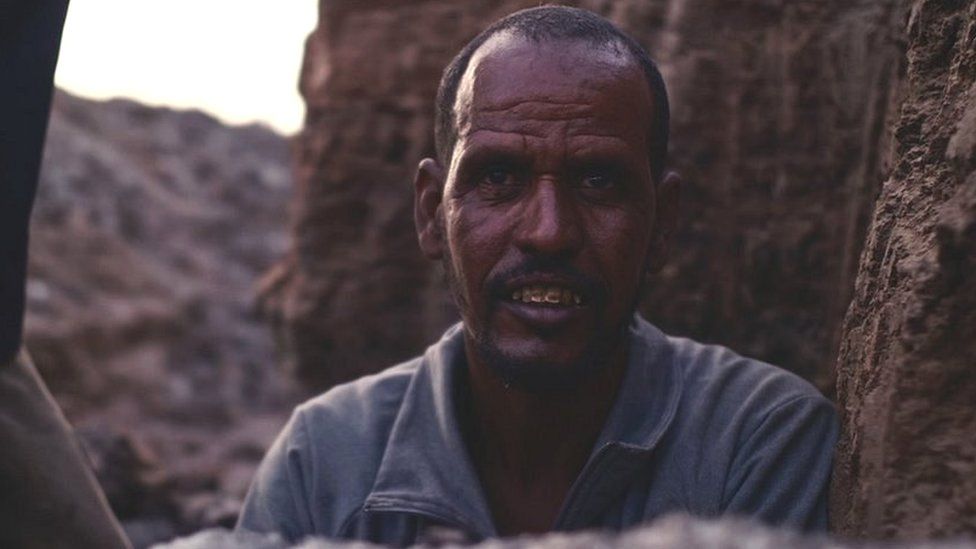

'Heat like fire'

"I come from a place of heat," Sidi Fadoua says. But the heat in northern Mauritania, in west Africa, it is now too hot for many people to live and work. The heat here is not normal heat, he says. "It's like fire."

Sidi, 44, lives in a small village close the edge of the Sahara. He works as a salt miner in the nearby flats. The work is tough, and it's become harder as the region heats up due to climate change. "We can't endure such temperatures," he says. "We are not machines."

To avoid temperatures upwards of 45C in the summer, Sidi has begun to work at night.

Job prospects are scarce. Those who once made a living raising livestock can no longer do it - there aren't any plants for the sheep and goats to graze.

So like an increasing number of his neighbours, Sidi has plans to migrate to the coastal city of Nouadhibou, where the ocean breeze keeps the city cooler. Locals can hitch a ride there on one of the world's longest trains, taking iron ore from nearby mines to the coast.

"People are moving from here," Sidi explains. "They cannot stand the heat anymore." The 20-hour ride is dangerous. Locals can sit on top of the carriages where they are exposed to heat and sunlight during the day, before temperatures plummet to near freezing at night.

In Nouadhibou, he hopes to find work in the fishing industry. The breeze may bring respite, but with increasing numbers escaping the desert heat, work opportunities are harder to find. Sidi remains hopeful.

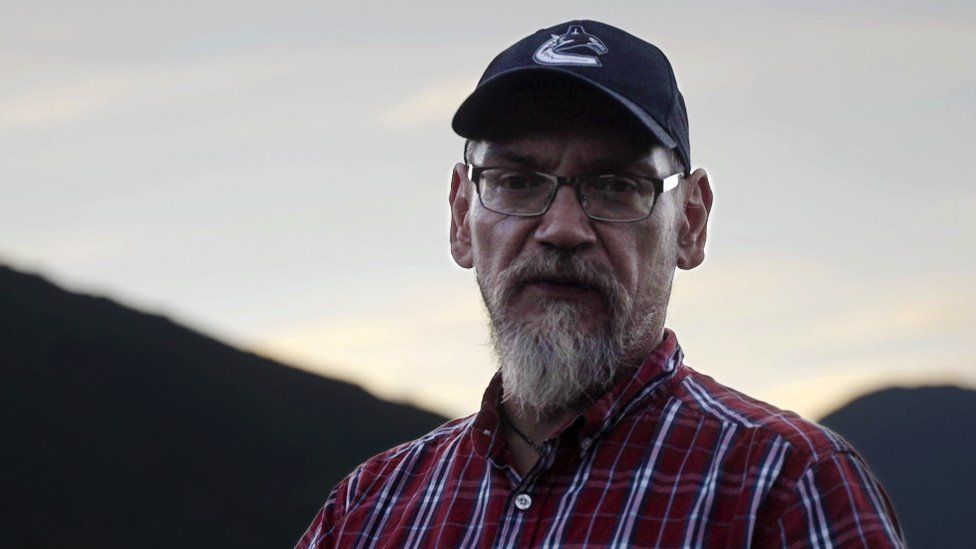

'How do you put an inferno out?'

Patrick Michell, chief of the Kanaka Bar First Nation, first began noticing worrying changes in the forest near his reserve in British Columbia, Canada, more than three decades ago. There was less water in the rivers, and mushrooms had stopped growing.

This summer his fears came true. A heatwave was sweeping across North America. On June 29, his home town of Lytton smashed records, reaching 49.6C. The next day, his wife sent him a photo of a thermometer reading 53C. An hour later, his town was on fire.

His daughter, Serena, eight months pregnant, scrambled to pack her children and pets into the car: "We left with the clothes on our backs. The flames were three storeys high and right beside us."

Patrick raced back to see if he could save the house. He'd grown up dealing with wildfires. But like the climate, the fires had changed too. "These aren't wildfires anymore, they're infernos," he says. "How do you put an inferno out?"

Despite the family's circumstances, Patrick sees what's happened as an opportunity: "We can rebuild Lytton for the environment that's coming in the next 100 years. It's daunting, but in my heart there's that optimism."

'When I was a kid, it wasn't like this'

"When I was a kid the weather was not like this," says Joy, who lives in the Niger Delta, in Nigeria. The region is one of the most polluted regions on Earth, and hotter days and nights are increasing.

Joy provides for her family by using heat from gas flares to dry tapioca and sell it at a local market. "I have short hair," Joy explains, "because if I grow my hair long, it could burn my head if the flare shifts direction or explodes."

But the flares are part of the problem. Oil companies use them to burn off gas that is released from the ground when they drill for oil. The flares, which rise 6m (20ft) high, are a significant source of global CO2 emissions, which contribute to climate change.

Climate change has had a devastating impact here, turning fertile lands into deserts in the north, while flash flooding has hit the south. People do not remember such extreme weather growing up.

"Most people here aren't well-informed enough to explain why the climate is changing rapidly," Joy says. "But we're suspicious of the non-stop flares." She wants the government to ban gas flaring, even though she relies on it to provide for her family.

Almost none of the oil wealth has been reinvested in Nigeria, where 98 million people live in poverty. This includes Joy and her family. For five days of work they make £4 in profit.

She is not optimistic about the future. "I think that life [on Earth] is now coming to an end."

'This heat is not normal'

Six years ago, Om Naief began planting trees on a patch of desert by a motorway. A retired civil servant in Kuwait, she was concerned by the increasingly severe summer temperatures and worsening dust storms.

"I spoke to some officials. They all said it was impossible to plant anything in the sand," she says. "They said the land was sandy and the temperature was too high. I wanted to do something that would astonish everyone."

Om lives in the Middle East, which is warming faster than much of the world. Kuwait is careering towards unbearable temperatures - it is regularly hotter than 50C. Some predictions suggest average temperatures will rise by 4C by 2050. Yet Kuwait's economy is dominated by fossil fuel exports.

The two patches Om planted are modest but they serve a purpose. "Trees fend off dust, eliminate pollution, clean the air, and lower temperatures," she says. Hedgehogs and spiny-tailed lizards now visit the site. "There's fresh water and shade. It's a beautiful thing."

Some Kuwaitis are now calling for a large-scale green belt to be planted by the government. Their shared hope is that Kuwait is ready to make a stand against the climate crisis. Om says they must protect the land and not let it dry out.

"This heat is not normal," Om concludes. "This is our fathers' land. We must give back to it, because it has given us a lot."

31 October 2021

bbc