For the past several years, a small group of scientists has warned that sometime early this century, the rate of global warming — which has remained largely steady for decades — might accelerate. Temperatures could rise higher, faster. The drumbeat of weather disasters may become more insistent.

Is climate change speeding up? Here’s what the science says.

In a paper published last month, climate scientist James E. Hansen and a group of colleagues argued that the pace of global warming is poised to increase by 50 percent in the coming decades, with an accompanying escalation of impacts.

According to the scientists, an increased amount of heat energy trapped within the planet’s system — known as the planet’s “energy imbalance” — will accelerate warming. “If there’s more energy coming in than going out, you get warmer, and if you double that imbalance, you’re going to get warmer faster,” Hansen said in a phone interview.

Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist with Berkeley Earth, has similarly called the last few months of temperatures “absolutely gobsmackingly bananas” and noted, “there is increasing evidence that global warming has accelerated over the past 15 years.”

But not everyone agrees. University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann has argued that no acceleration is visible yet: “The truth is bad enough,” he wrote in a blog post. Many other researchers also remain skeptical, saying that while such an increase may be predicted in some climate simulations, they don’t see it clearly in the data from the planet itself. At least not yet.

The Washington Post used a data set from NASA to analyze global average surface temperatures from 1880 to 2023.

The record shows that the pace of warming clearly sped up around the year 1970. Scientists have long known that this acceleration stems from a steep increase in greenhouse gas emissions, combined with efforts in many countries to reduce the amount of sun-reflecting pollution in the air. But the data is much more uncertain on whether a second acceleration is underway.

Between 1880 and 1969, the planet warmed slowly — at a rate of around 0.04 degrees Celsius (0.07 Fahrenheit) per decade. But starting around the early 1970s, warming accelerated — reaching 0.19 C (0.34 F) per decade between 1970 and 2023.

That acceleration isn’t controversial. Prior to the 1970s and 1980s, humans were burning fossil fuels — but also were releasing huge amounts of air pollution, or aerosols. Sulfate aerosols are lightly colored particles that have the ability to temporarily offset part of the warming caused by fossil fuels. They reflect sunlight back to space themselves, and also influence the formation of reflective clouds.

The more aerosols in the air, the slower the planet will heat up: a trade-off that Hansen calls a “Faustian bargain.” The idea is that because the aerosol pollutants have dangerous health effects on people, eventually societies decide to clean them up — causing dramatic warming to reveal itself in the process.

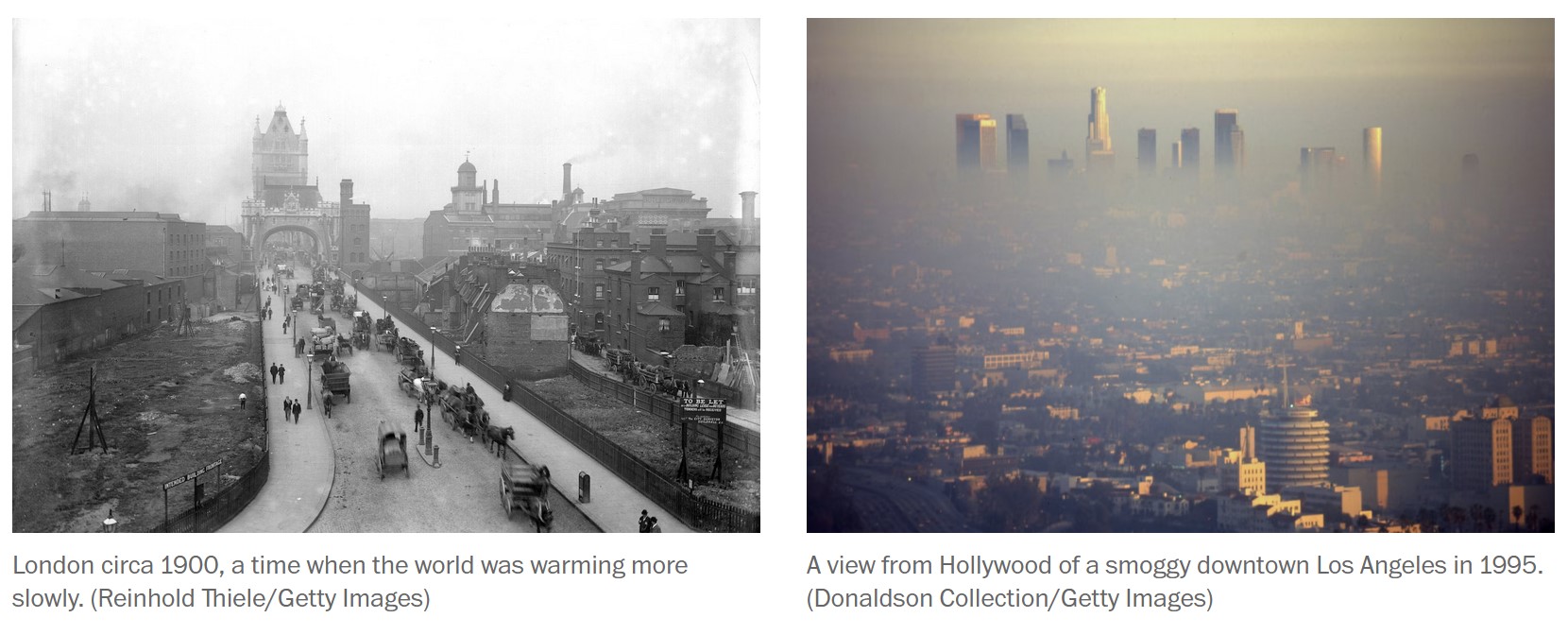

In the early and mid-20th century, developed countries were so heavily polluted that the world was warming slowly. “This was the era of the London fogs and of very extreme pollution in the U.S.,” said Gabi Hegerl, a climatologist at the University of Edinburgh. A recent study in the Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, for instance, found that in the 1980s these particles offset approximately 80 percent of climate warming.

Since the 1970s and 80s, however, the influence of aerosol pollution has leveled off, thanks in part to policies like the U.S. Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. As the figure above shows, at the same time, greenhouse gas emissions have climbed — leaving aerosols unable to keep up. The result is a planet that is warming much faster now than in the first half of the 20th century.

But the data is murkier when it comes to whether the pace of warming over the past few decades has quickened even more — an increase that could accelerate the wildfires, floods, heat waves and other impacts around the globe. It may require more years of evidence to clear the statistical hurdles that climate science demands.

“I think we probably need maybe three or four more years" of data, said Chris Smith, a climate scientist at the University of Leeds. “It’s just a bit too early right now.”

Scientists are wary, in part, because some had reached the opposite conclusion roughly a decade ago. Back then, a few scientists and many political commentators suggested that the rate of climate change had stalled or was slowing down. The case for what some called a warming “hiatus” was never especially strong — and in retrospect it does not appear that the rate of warming substantially changed — but it serves as a cautionary note about declarations that warming is getting faster or slower.

To see why matters are currently ambiguous, consider the following “trend of trends” figure, based on an analysis by Mark Richardson, a climate scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who published a statistics paper last year that found that an acceleration of warming is not yet clearly detectable.

Richardson looked at each 30-year trend in the NASA temperature record, starting with the period from 1880 to 1909 and ending with the period from 1994 to 2023. Higher values indicate higher rates of global warming. Here, we show the result from the period between 1941 and 1970 onward, to better tease out how the rate of warming changed in the second half of the 20th century, and whether it is still changing now:

While there is a hint of an increasing warming rate at the very end of the record, it is nowhere nearly as pronounced as the shift since 1970. This helps explain why many scientists are remaining noncommittal, for now, on acceleration.

“The temperature near the Earth is only a thin layer, and it’s easy for the temperatures to swing about a lot,” Richardson said. For this reason, it takes longer for scientists to be sure that a change is outside what you would normally expect, he said.

But some scientists believe that the temperature data is simply not yet showing an impending acceleration.

Hansen argues that recent changes in aerosols will cause a strong increase in the warming rate in just the next few years. In 2020, the International Maritime Organization instituted a rule requiring a substantial reduction in the sulfur content of fuel oil. Sulfate aerosol pollution from ocean shipping plunged.

Much of the current debate over whether warming is getting faster turns on the consequences of these maritime changes, which have the potential to affect how much heat is being absorbed over enormous stretches of the world’s oceans. Hansen and his co-authors argue that the change in ship emissions is contributing to a major increase in the Earth’s energy imbalance — the extra amount of heat that is staying within the Earth system rather than escaping to space. But not all scientists agree that the pollution regulations for oceangoing vessels have had such an outsize impact.

Hansen acknowledges that the global surface temperature data, alone, isn’t presenting an entirely clear picture of acceleration yet – but he predicts that it will be soon, as temperatures spike much further in the current El Niño.

“There won’t be any argument [by] late next spring, we’ll be way off the trend line,” Hansen said.

Some climate models also predict an acceleration of warming in the years to come, as aerosols decline. “While there is increasing evidence of an acceleration of warming, it’s not necessarily ‘worse than we thought’ because scientists largely expected something like this,” said Hausfather.

Most agree that it’s too early to tell if the second acceleration is underway. “Trying to estimate the underlying rate of warming from a short time period is really hard,” said Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at Texas A&M University.

“Just because you get a trend that looks like it’s really rapid — that doesn’t tell you what the underlying rate of warming is.”