Burning planet: why are the world’s heatwaves getting more intense?

In March, the north and south poles had record temperatures. In May in Delhi, it hit 49C. Last week in Madrid, 40C. Experts say the worst effects of the climate emergency cannot be avoided if emissions continue to rise

But that was not all. At the north pole, similarly unusual temperatures were also being recorded, astonishing for the time of year when the Arctic should be slowly emerging from its winter deep freeze. The region was more than 3C warmer than its long-term average, researchers said.

To induce a heatwave at one pole may be regarded as a warning; heatwaves at both poles at once start to look a lot like climate catastrophe.

Since then, weather stations around the world have seen their mercury rising like a global Mexican wave.

A heatwave struck India and Pakistan in March, bringing the highest temperatures in that month since records began 122 years ago. Scorching weather has continued across the subcontinent, wreaking disaster for millions. Spring was more like midsummer in the US, with soaring temperatures across the country in May. Spain saw the mercury hit 40C in early June as a heatwave swept across Europe, hitting the UK last week.

Scientists have been able quickly to prove that these record-breaking temperatures are no natural occurrence. A study published last month showed that the south Asian heatwave was made 30 times more likely to happen by human influence on the climate.

Vikki Thompson, climate scientist at the University of Bristol’s Cabot Institute, explained: “Climate change is making heatwaves hotter and last longer around the world. Scientists have shown that many specific heatwaves are more intense because of human-induced climate change. The climate change signal is even detectable in the number of deaths attributed to heatwaves.”

Friederike Otto, senior lecturer in climate science at the Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, said heatwaves in Europe alone had increased in frequency by a factor of 100 or more, caused by human actions in pouring greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. “Climate change is a real game changer when it comes to heatwaves: they have increased in frequency, intensity and duration across the world,” she said.

This type of heat poses a serious threat to human health, directly as it puts stress on our bodies, and indirectly as it damages crops, causes wildfires and even harms our built environment, such as roads and buildings. Poor people suffer most, as they are the ones out in fields or in factories, or on the street without shelter in the midst of the heat, and they lack the luxury of air-conditioning when they get home.

Air-conditioning itself is a further facet of the problem: its growing use and massive energy consumption threatens to accelerate greenhouse gas emissions, just as we need urgently to bring them down. Radhika Khosla, associate professor at the Smith School at the University of Oxford, said: “The global community must commit to sustainable cooling, or risk locking the world into a deadly feedback loop, where demand for cooling energy drives further greenhouse gas emissions and results in even more global warming.”

There are ways to reduce the impacts for individuals, and to adapt our cities. Painting roofs white in hot countries to reflect the sun’s rays, growing ivy on walls in more temperate regions, planting trees for shade, fountains and more green areas in cities can all help. More heavy-duty adaptation measures include changing the materials we use for buildings, transport networks and other vital infrastructure, to stop windows falling out of their frames, roads from melting in the heat and rails from buckling.

But these measures can only ever be a sticking plaster – only drastic cuts in greenhouse gas emissions will prevent climate chaos. The current heatwaves are happening as the earth has warmed by about 1.2C above pre-industrial levels – nations agreed, at the Cop26 UN climate summit last November, to try not to let them rise by more than 1.5C. Beyond that, the changes to the climate will be too great to overcome with shady trees or white roofs, and at 2C an estimated 1 billion people will suffer extreme heat. “We cannot adapt our way out of the climate crisis,” Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy, told the Observer. “If we continue with business-as-usual greenhouse gas emissions, there is no adaptation that is possible. You just can’t.”

Fiona Harvey

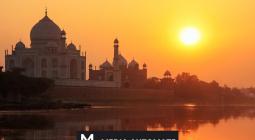

India

Even the mountains, the traditional escape from the unbearable city heat, now offer little respite

Every summer, when the heat in the plains becomes unbearable, software engineer Akhilesh Gupta does what the British used to do when they ruled India – pack the family into the car and head out of New Delhi for a long drive to enjoy the cool air of the mountains.

This year, the family couldn’t wait to go. Since mid-March, the Indian capital has been in the grip of a relentless heatwave with temperatures hovering about 45C, making living and working insufferable.

In earlier years, such high temperatures used to be a fleeting feature of the summer. This year, they are the new normal. Demand for power has soared as Indians use more air conditioners. Water shortages have hit some areas. Those who work outside – construction labourers, autorickshaw wallahs, security guards – are among the worst affected.

Street vendors selling fruit, vegetables and flowers have been cowering under makeshift awnings for shade while constantly splashing water on to their produce to keep it from shrivelling up.

The Guptas reached their destination in Nainital, more than 2,000m above sea level, to find that the town was having the hottest summer for 30 years. One day it touched an unprecedented 34C.

“I have been coming here every summer since I was a kid and have never needed a ceiling fan. It never used to go beyond 28C. We couldn’t go boating it was so hot. It was better than Delhi but it was a huge shock to us,” said Gupta.

His friends went trekking to even higher altitudes and found that mountains usually covered in snow had only a dusting.

Heatwave conditions have affected most areas of India since March. Data from the Meteorological Department shows that Delhi has recorded a maximum temperature of 42C (and above) on 25 days since the summer began – the highest number of days since 2012. March was the hottest in India since records began 122 years ago.

The kind of crop damage that climate experts have predicted is already happening. Farmers in north India have seen their wheat being burnt by the sun. An estimated 15 to 35% of the wheat crop in states close to Delhi – Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, India’s “wheat bowl” – has been damaged.

Climate experts say heatwaves are what lie ahead for Delhi. Their estimates suggest that Delhi has become so built-up that it has lost 50 to 60% of its wetlands and natural ecosystem that could have moderated the temperatures.

In fact, Abinash Mohanty, programme lead at the Council for Energy, Environment and Water, wants the definition of a “heatwave” to be updated. He says heatwaves should not be restricted to days when the temperature crosses a certain officially ordained figure because for most poor Indians living in slums in homes with tin roofs, the temperature is always five to six degrees hotter than outside.

“People in Delhi will experience extreme discomfort in the coming years. Their health and productivity will be impacted, along with their cognitive health, because if you can’t sleep at night, you can’t function the next day,” said Mohanty.

Female construction workers already suffer health issues. “There aren’t any clean public toilets around so I limit my water intake to avoid having to go to the toilet. Last month I ended up in hospital with dehydration,” said Sunita Devi, who is carrying rubble away from a construction site in Friends Colony West.

A 2019 International Labour Organization report, Working on a Warmer Planet, predicted that India is expected “to lose the equivalent of 34 million full-time jobs by 2030 as a result of heat stress”.

Individuals are already feeling the impact. The lives of people such as Virender Sharma, who sells flowers on the street, have become harsher. With the sun shrivelling the flowers, his income has dropped drastically. The daily discomfort is getting to him.

“There is nothing I can do to cool down. I splash water on myself but it’s boiling hot,” he said, fanning himself in vain with one of his palm fronds.

Amrit Dhillon in New Delhi

Spain

Distressed swifts fall from their nests, wildfires rage – and everyone wants a slot at the municipal pool

The tree-lined streets of the Tiro de Línea neighbourhood in the southern city of Seville have long played host to a little-known guest: one of Spain’s largest swift colonies.

The birds burst into public view this week, however, as the most visible symptom of the days-long heatwave that has gripped much of the country.

“It was Dante-esque,” said Maria del Mar Molina, one of the volunteers who went to check on the colony last week. “There were hundreds of dead birds and hundreds of others that were alive but suffering.”

The heatwave – one of Spain’s earliest on record – had transformed their nests into ovens just as the hatching season was under way. Ecologists estimate that thousands of chicks fled their nests before they could fly.

“It breaks your heart,” said Del Mar Molina, one of dozens of volunteers who have been patrolling the pavements to collect birds that could be nursed back to health. “This is a protected species, there should be some sort of climate emergency protocol for these kinds of heatwaves.”

This sense – that Spain needs to prepare for a heating world – echoed across the country as it grappled with a pre-summer heatwave that sent temperatures soaring above 43C in parts of the country.

“Spain is traditionally a very hot country but it’s getting even hotter,” said Rubén del Campo, the spokesperson for the state meteorological agency Aemet. The week-long wave of heat arrived as Spain was still reeling from the hottest May in 58 years. “In less than a month we have had two very rare episodes of extreme heat,” he said.

In eight of the country’s 17 regions, firefighters scrambled to quell more than a dozen wildfires. In the north-west region of Castilla y León, flames swallowed more than 20,000 hectares (49,400 acres) and forced the evacuation of hundreds of people.

Few escaped the suffocating blanket of heat that hovered over much of Spain. “People are exhausted,” said Nuria Chinchilla, a professor and founder of the International Centre for Work & Family at the IESE business school.

At a meeting last week, executives told her that they had been allowing employees to work through lunch and leave early. “They had noticed that the heat was affecting productivity.”

Similar debates swirled at schools across the country. In Catalonia, teachers flooded social media with photos showing classrooms sweltering in 30C heat as they protested that many schools still only have fans to counter it.

''The school is an oven,” wrote one resident. “This is not how to teach or learn, it’s how to make a roast.”

In Madrid, residents scrambled for the hottest ticket in town: a spot at the municipal swimming pools. In a city with an estimated one municipal swimming pool for every 157,000 residents, that was far from easy.

Those who managed to master the fickle app to snap up slots that went on sale 49 hours in advance, still had to beat the crowd.

“It’s impossible,” said Josué González Pérez, 33, after trying for two days without success. “I’ll be staying at home with the fan on.”

With many across Spain counting down to Sunday, when the heat was forecast to dissipate, Del Campo warned of a broader pattern.

“In the past decade, heatwaves have been twice as frequent as in previous decades,” he said. “So what is extraordinary now will end up being normal.”

Ashifa Kassam in Madrid

United States

In Phoenix, the country’s hottest city, the temperature hasn’t dropped below 27C for two weeks

More than 100 million Americans were urged to stay indoors over the past week, as record-breaking temperatures left multiple people and thousands of cattle dead.

As temperatures climbed to unseasonable highs, tens of thousands of people across Ohio, Michigan and Indiana in the midwest were left sweltering without power after storms and flooding damaged transmission lines.

Two women were confirmed dead in Wisconsin, while in Arizona, the Maricopa county coroner’s office is investigating 48 possible heat-related deaths dating back to April. The true death toll is likely to be higher but heat fatalities are not reportable.

Extreme heat is America’s leading weather-related killer, and Phoenix in Maricopa county is the country’s hottest and deadliest city.

“You never get used to this heat, but we have to deal with it,” said Kim Gallego, 46, a Phoenix city parks employee with a heat rash on her legs. Gallego starts work at 5am and on Thursday it was already 44C by the time she knocked off at 1.30pm.

On Wednesday, at least 16 US cities set or equalled daily records, according to the National Weather Service. Excessive heat warnings were issued for parts of the country less accustomed to scorching temperatures, especially so early in the season.

In Kansas, a state with twice as many cows as people, 2,000 animals were reported dead due to stress caused by a combination of high temperatures and humidity.

Heat advisories remain in place across the south-east and midwest – from Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi to Kansas, Missouri and Minnesota on the Canadian border – and are forecast to extend to east coast states such as the Carolinas, where humidity levels will make it feel even hotter. Summer doesn’t officially start until 21 June.

In Phoenix, America’s fifth largest city with 1.6 million habitants, temperatures have topped 38C every day in June, breaking several daily records with little respite at night. The temperature has not fallen below 27C since the early hours of 7 June. The impact of heat is cumulative and the body only begins to recover when temperatures drop below 27C.

The city is a sprawling urban heat island, where heat-trapping concrete and asphalt have replaced desert and farmland to exacerbate the impact of global heating.

The extreme heat is especially hard for those working or living outdoors or without air conditioning.

Sareptha Jackson, 60 and Jerry Stewart, 69, spent another week sweltering in their rented apartment where the air conditioning has been broken for three years. Even with fans running continuously, the temperature inside their apartment hovered about 32C.

The couple have been assessed for emergency housing since the Guardian last week reported the dangerously hot conditions, and with higher temperatures on the way, the move can’t come soon enough. “We can’t wait to be somewhere cool, it will be a new beginning for us,” said Jackson.

Michael McCabe, 23, a valet at a hotel in central Phoenix, said: “I’ll go home and jump in the pool to cool down. After that I’ll be sitting next to a fan for the rest of the night.”

Heat deaths are preventable but rising. The frequency, duration and intensity of heatwaves have been rising steadily over the past 50 years, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Nina Lakhani in Phoenix, Arizona

Fiona Harvey, Ashifa Kassam in Madrid, Nina Lakhani in Phoenix, and Amrit Dhillon in New Delhi | Guardian