Big polluters given almost €100bn in free carbon permits by EU

Free allowances ‘in direct contradiction with the polluter pays principle’, WWF report says

Big polluting industries have been given almost €100bn (£86bn) in free carbon permits by the EU in the last nine years, according to an analysis by the WWF. The free allowances are “in direct contradiction with the polluter pays principle”, the group said.

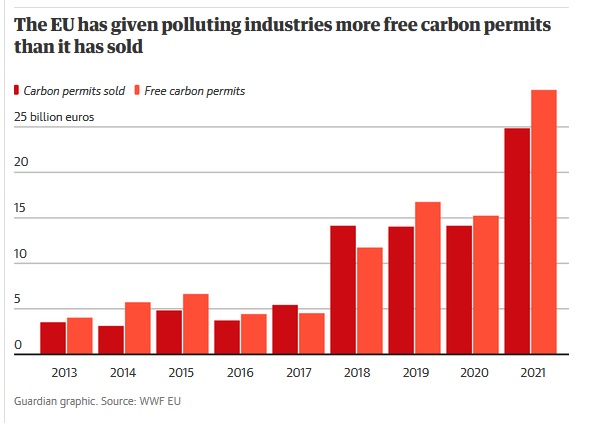

Free pollution permits worth €98.5bn were given to energy-intensive sectors including steel, cement, chemicals and aviation from 2013-21. This is more than the €88.5bn that the EU’s emissions trading scheme (ETS) charged polluters, mostly coal and gas power stations, for their CO2 emissions.

Furthermore, the WWF said, the free permits did not come with climate conditions attached, such as increasing energy efficiency and some polluters were also able to make billions in windfall profits by selling the permits they did not use.

The European Commission describes the ETS as “a cornerstone of the EU’s policy to combat climate change and its key tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions cost-effectively”. The number of carbon emissions permits is reduced annually, which in recent years has pushed up the permit price and incentivised companies to reduce their emissions.

Carbon emissions covered by the ETS have fallen by 37% since it began in 2005, largely thanks to the growth of renewable energy. But the WWF said the free allowances had undermined the ETS and emissions from heavy industry had not fallen. The analysis also found that at least a third of the revenue raised from the ETS was not spent on climate action, rising to almost half if projects to increase the efficiency of burning fossil fuels were excluded.

Reform of the ETS is being negotiated between the European parliament, Council and Commission. Potential dates for the end of free allowances range from 2032 to 2036. The free allowances were originally justified to tackle the potential risk that industrial companies might move production outside the EU to avoid carbon taxes, but the WWF said there had been no evidence for this.

“The analysis shows that for the last decade, the ETS was based on a ‘polluters-don’t-pay principle’, with billions and billions of forgone revenue that EU countries could instead have invested in industrial decarbonisation,” said Romain Laugier, at the WWF’s European policy office and lead author of the report. “EU negotiators should phase out free allowances as soon as possible, and in the meantime make sure companies that receive them meet strict conditions on cutting their emissions.”

Alex Mason, also at the WWF, said: ‘If taxpayers are going to forgo tens of billions in revenue, then industry should be using that money to invest in the technologies to decarbonise, certainly not simply doing nothing or even profiting from the free allowances.”

The sums being raised by the ETS are rising sharply as the post-Covid recovery has increased economic activity and driven up the ETS carbon price. In 2022, the ETS is expected to raise about €33bn.

WWF said 100% of this should be invested in climate action, both because of the urgency of the climate crisis and to justify the carbon tax to citizens. The report found €25bn in ETS revenue had gone straight into government coffers from 2013-21.

A further €12bn was “questionable”, as it was used for new fossil fuel infrastructure in countries including Germany, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Croatia. “This is very bad in climate terms because it locks consumers into expensive, unreliable fossil fuels,” Laugier said.

“It’s really important to show citizens that the ETS is tackling climate change,” he said, noting the strong gilet jaunes protest in France in 2018 against a vehicle fuel tax rise. Strict definitions of climate action that exclude fossil fuels were needed to direct how ETS revenue was spent, the WWF sai

The report excludes the UK, which left the EU in January 2020. But before Brexit, UK companies were among those making big profits from selling excess free carbon allowances, along with those in Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

A 2021 assessment from Carbon Market Watch reported that steel, cement, petrochemical and refinery companies had made windfall profits of up to €50bn between 2008 and 2019. In addition, some industrial companies that had to buy carbon permits have later received government compensation for the costs.

“There hasn’t been any evidence ever of industries deciding to move their production elsewhere because of the carbon price rises,” said Laugier, meaning the potential risk had been placed above the reality of almost €100bn being lost to governments. The EU is also looking to introduce border taxes on high carbon imports from outside the bloc.

The report concludes: “We have very little time left to keep global temperature rise to 1.5C and stop runaway climate change, and how we spend public money is critical. It seems clear that issuing free allowances under the ETS has been a serious policy failure.”

A spokesperson for the European Commission said: “The EU ETS has successfully contributed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the power and industry sectors by well over 40% since it entered into force in 2005.”

“The number and share of free allowances has continuously decreased since 2005. The commission has also proposed to further reduce the number of allowances granted for free from 2026 onwards,” he said. “On the use of ETS revenues, our latest draft legislation would require member states to spend 100% of their ETS revenues on climate action.”

cover photo: Steel is among the energy-intensive sectors to have benefited from the free pollution permits. Photograph: Wolfgang Rattay/Reuters