What’s driving mobility into the 2020s?

Road transport faces a number of challenges heading into the next decade, as competition, environmental and social issues all exert influence over the sector. Here is an overview of the challenges on the road ahead.

For all matters related to EU transport policy, check out our dedicated hub and newsletter.

POWER

The European Commission advocates for a technological-neutrality approach to policy-making and has therefore stopped short of explicitly backing one specific power-train option.

That has not stopped the EU executive from guiding policy in one particular direction though and all signs point to the Commission preferring electric battery mobility over other technologies.

Provisions in new CO2 rules for 2030 include rewarding member states with less stringent targets in return for boosting the sales of low- and zero-emission vehicles. Given the market-readiness of car types, electric vehicles are in pole position.

The Commission has also invested significant resources in the European Battery Alliance, a new platform designed to capture a global market that could be worth an estimated €250 billion per year.

EVs are not the only option though. Carmakers and industry groups insist that electrification is “not a silver bullet” for the sector’s problems and inroads have been made into other technologies.

***

Electric

Overall sales figures are on the rise. In 2019, half a million could be sold in Europe, after records were broken every month up until August. Current estimates put this year’s new car sales at 3% of the market.

Some of Europe’s top auto players, including BMW, Citroen, Renault and Volkswagen already offer EVs as part of their normal car lineup. Renault’s ZOE, VW’s e-Golf and BMW’s i3 were all among the top EU sellers in 2018.

Others have been slower to go electric. Mercedes, Peugeot and Volvo have all announced forays into the market but others like Fiat have dragged their feet further still.

Earlier this year, parent company FIat-Chrysler (FCA) explored a commercial tie-up with Renault, which ultimately came to nothing. Part of the reason behind the idea was to leverage the French firm’s EV know-how, in return for a foothold in the US market.

Fiat’s slow start on low-emission tech forced it to shell out nearly €2 billion to US carmaker Tesla in 2019, in return for pooling carbon emission credits. Strict emission targets in the EU and the US meant the Cinquecento-manufacturer had to resort to accountancy tricks.

The fortunes of Elon Musk’s Tesla outfit have incrementally risen in recent years. According to its records, it already amassed $1 billion in similar credit-pooling schemes in 2019, while its Model 3 also became the EU’s top-selling EV this year.

In Norway, which boasts cheap power and a strong charging network, the Model 3 emerged as the top-selling car outright in quarter 3. Thanks to a tax exemption for battery-powered vehicles, the Nordic nation records the most per capita sales in the world.

Electric also only offers a viable solution to decarbonise light vehicles like cars and vans, as the power-to-weight ratio needed for heavier transport is still an obstacle. There is progress in developing e-trucks but range and charger availability still worry operators.

**

Biofuels

Biofuels have the potential to be low-carbon options but suffer from a bad reputation, as in the past the land needed to grow the crops was procured by removing carbon sinks like forests and wetlands.

That space was also used for fuel rather than food production, thanks to incentives put in place by governments on both sides of the Atlantic.

The most popular options available to the transport sector at the moment are bioethanol (made from sugar and cereal crops), which displace petrol, and biodiesel (made mainly from vegetable oils), which substitute conventional diesel.

In an effort to make a distinction between the ‘bad and the good’, the Commission adopted new sustainability criteria for biofuels in March 2019, which assign a rating to biofuels that have a high risk of causing environmental damage and those that do not.

Biofuels that have a high risk of indirect land-use change (ILUC), namely, deforesting land that would otherwise absorb carbon out of the atmosphere, will be banned in the EU after 2030.

One of the main selling-points of biofuels is that they can be used with existing powertrains and infrastructure, reducing the need to roll out expensive charging points and phase out conventionally-powered vehicles.

Bioethanol and biodiesel both emit carbon dioxide when burned, although the amount is much lower than their fossil fuel equivalents. Their role in the fight against climate change has also been acknowledged by the United Nations’ top scientists.

In its landmark report on the effects of global warming, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicated that limiting global temperature increase should involve a mixture of electricity and biofuels in the transport sector.

IPCC scientists said that a biofuel share of 2%, 5.1% and 26.3% for 2020, 2030 and 2050, respectively, would chart an appropriate path towards curbing emissions and curbing average warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius.

That report also said that electricity should increase to 1.2%, 5% and 33% along the same timeframe, meaning that biofuel-powered vehicles would remain as important as e-cars up until the end of the next decade.

So-called advanced biofuels are made from waste residues from agriculture and forestry, non-food crops like grasses and algae or industrial waste. They generally lack the ILUC shortcomings of the first generation of biofuels.

However, their development is still in its infancy, costs are higher and it is difficult to produce them in the quantity needed to make a significant impact on the sector. New EU rules on renewable energy offer incentives to use them though, which should increase their availability.

**

Hydrogen

Hydrogen power has long threatened to revolutionise the transport sector, as it has the potential to offer emission-free mobility and long range and satisfy the needs of heavy vehicles. Like biofuels, it could also be used in shipping.

But the development of the technology has stalled thanks to a mixture of cost-concerns, lack of regulatory certainty and doubts over whether its emission-free potential can actually be unlocked.

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), 95% of global hydrogen production is done using fossil fuels and 48% of that is produced from natural gas. Just 4% is done using electrolysis.

Environmental groups insist that the tumbling costs of renewable energy, whose price per megawatt now rivals nuclear and most fossil fuels, mean cheap hydrogen produced by solar and wind power is not far away.

Few carmakers have taken the leap into the hydrogen market, as customers are put off by the lack of fuelling stations and cost. Sales in Europe are outstripped by those in Japan and the US, thanks to a mix of choice and increased-range needs.

In October, the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) signed up to a joint declaration with industry group Hydrogen Europe and the International Road Transport Union (IRU) calling on the EU to prioritise infrastructure like refuelling stations.

“Hydrogen technology acts as a bridge between the energy and transport sectors (sectoral integration), offering solutions for a better integration of surplus renewable energies,” the communication explains.

“Unfortunately, hydrogen refuelling infrastructure is severely lacking today, putting at risk the development of this innovative zero-emission solution. A clear signal and commitment to support 2/4 the deployment of hydrogen refuelling infrastructure is urgently needed,” it adds.

The text calls on the Commission to revise the Alternative Fuels Directive to include mandatory targets for hydrogen refuelling points and to draft an overall strategy to identify where the infrastructure is needed most.

During his hearing at the European Parliament, the bloc’s incoming climate chief, Frans Timmermans, acknowledged the role of hydrogen in decarbonising the EU’s economy, suggesting that he will be an ally when the new Commission takes office.

**

E-fuels

Another outlet for hydrogen is synthetic fuels or e-fuels, which are produced by combining renewables-produced hydrogen with carbon dioxide, in order to produce a fuel that is comparable to conventional petrol.

That means that there is no need for new refuelling infrastructure or vehicle design, as e-fuels can be used in the current generation of cars and dispensed from regular pumps.

Germany’s automobile association (VDA) says that the fuels are “a promising avenue” and that “highly efficient internal combustion engines running on synthetic fuels” will be needed alongside battery mobility to meet EU climate targets.

But the costs are currently prohibitive. Estimates put the price-per-tonne of the process at nearly €3,000, far exceeding the €500 for conventional fuels.

There are also concerns about the energy efficiency of the process when it comes to power use. Battery vehicles are between four and six times more efficient and even hydrogen is twice as efficient.

A 2017 study by the German Energy Agency (DENA) concluded that 70% of transport sector demand will be met by e-fuels in 2050, although it acknowledged that most of that will be in the heavy, maritime and aviation sectors.

“E-fuels are currently in the phase of demonstration and very early market penetration. A suitable legal and economic framework is essential to encourage more investment in fuel production efficiency, to reduce cost and to accelerate market uptake,” the study explains.

“From an economic point of view, the transport sector could play the key role as it is not directly facing carbon leakage challenges and customers rather inclined to environmental sustainability,” it concludes.

Pilot projects have begun to take off. In Rotterdam, a new company has partnered with the city’s airport to produce 1,000 litres of jet e-fuel per day, by capturing carbon dioxide from the air and splicing it with green hydrogen.

It is supposed to be up and running by 2021 and the project’s architects insist that their fuel will be much cleaner than conventional kerosene.

“The beauty of direct air capture is that the CO2 is reused again, and again, and again,” Louise Charles, from Climeworks, the company which provides the direct air capture technology, told the BBC.

However, the scale of production would have to ramp up massively if it were to become a viable option for the airline industry. The 1,000 litres of e-fuel daily output, for example, would only power a Boeing 747 for about five minutes of flight.

TIMELINE

April 2019: The European Council gave the final green light to new rules governing CO2 emissions from light vehicles for 2030.

June 2019: The Council approved the final version of the EU’s first attempt at regulating CO2 emissions from heavy vehicles for the period up to 2030.

2020/21 light vehicles CO2 target: an EU-wide target of 95g per kilometre of CO2 is in force. Estimates in 2018 put the fleet average at 120.4g/km.

2020 renewables target: 10% in transport

Early 2020: Talks on road charges for heavy vehicles. The Council is yet to agree on its position, so inter-institutional negotiations will likely start in 2020.

2020: The incoming Commission of Ursula von der Leyen will publish a Climate Law within its first 100 days. Frans Timmermans will lead the work on the file.

2020: EU ministers and the incoming Commission have pledged to increase the bloc’s current 40% overall emissions reduction pledge for 2030. Depending on how ambitious the increase is, that could have a noted effect on other sectors.

2022: heavy vehicles legislation review

2023: light vehicles legislation review

2025: midway target of 15% reductions in both car and van emissions

2025: midway target of 15% reductions in heavy vehicle emissions

2030: 37.5% target deadline for cars, 31% for vans

2030: 30% target deadline for heavy vehicles

2030: 14% renewables target for road and rail under REDII

2035: likely target for more CO2 reductions in light and heavy vehicles, pending review

2040: likely target for more CO2 reductions in light and heavy vehicles, pending review

UP FOR REVIEW

EU legislation is not set in stone and review clauses built into laws commit the Commission to take stock at regular intervals. The EU executive can also decide to review rules that it deems inadequate or out of date.

The newly-brokered CO2 laws for light and heavy vehicles are no exception. In 2023, the cars legislation will be put under the microscope and its effectiveness assessed.

Factors like emission reductions achieved in the real world, the roll-out of charging and refuelling infrastructure and the impact of an incentive mechanism will all be checked and tweaks proposed if necessary.

The Commission could decide to change the 2025 and 2030 targets at that time. EU commitments to international agreements like the Paris Agreement suggest that any change would be to increase the ambition of the targets rather than water them down.

How emissions are actually monitored will also be up for discussion, as in 2023 the Commission will have to look into real-world test procedures using portable systems and monitoring life-cycle emissions in future CO₂ regulations.

Life-cycle emissions are the emissions produced along the whole car manufacturing chain, taking into account the raw materials used to make parts and components and the energy used in factories and on the road.

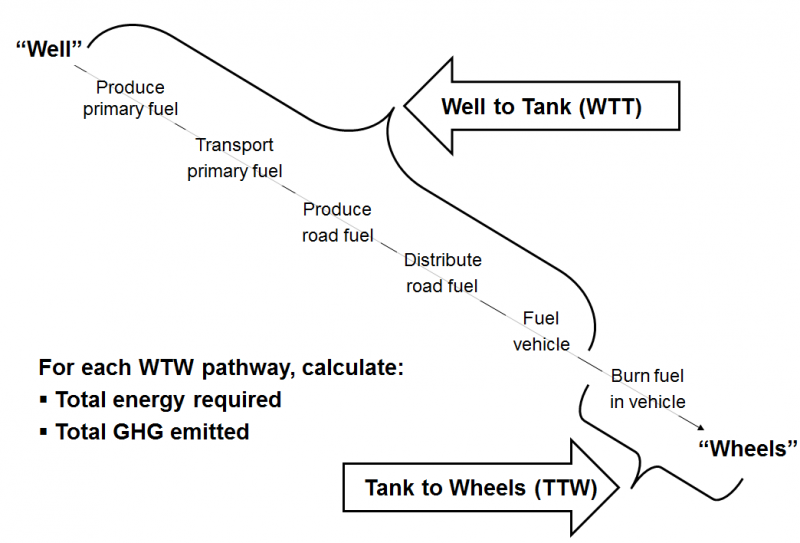

Parts of the car industry have argued that manufacturers should only have to concern themselves with so-called Tank-to-Wheel emissions, namely, whatever comes out of the exhaust. ACEA insistscarmakers can only control tailpipe emissions.

Other groups, like the IRU, advocate for the middle-ground and the Well-to-Wheel (WTW) approach, which takes into account all the emissions produced sourcing and transporting fuels, as well as the emissions produced by the car itself.

IRU chief Matthias Maedge told EURACTIV that “the efficiency of the vehicle and the decarbonisation potential of the fuel both have to be taken into account, because tail-pipe counting only isn’t enough”.

He added that the EU will badly fail its climate goals if the approach is not adopted in mid-decade for all new cars.

The Commission’s Science Hub, the JEC, has already done in-depth research into WTW and those findings will feed into its decision during the review period.

Targets beyond 2030 will also be considered during the stock-take and the EU executive is likely to propose at that time setting benchmarks for 2035 and 2040.

By the end of 2020, the EU will have subscribed to an overall 2050 climate goal that targets net-zero carbon emissions. Transport will have to make cuts just like other sectors so the gap between 2050 and 2030 will have to be bridged.

Other pieces of legislation could also be tweaked by the Commission, including the Alternative Fuels Directive and the Batteries Directive.

EU Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič will oversee battery policy for the next five years and revealed in an interview with EURACTIV that revising the directive, in order to improve standards and recycling, could be on the cards.

TRADE DYNAMIC

The future of Europe’s car industry is also heavily linked to global trade patterns. Exports totalled€128 billion in 2018, with the United States accounting for 29% of that output.

Germany unsurprisingly retained its title as king of the carmakers, as €70 billion of those exports came from vehicles built in the Bundesrepublik.

But developments at a multilateral level risk disrupting the industry, particularly when it comes to the lucrative transatlantic trade. US President Donald Trump has repeatedly threatened to slap heavy tariffs on car imports.

The White House has claimed that European cars pose a national security threat and “weaken the internal economy”, according to a report produced earlier this year.

Trump delayed imposing a 25% tariff on auto imports pending the outcome of trade talks with the EU, as well as Japan, but the volatile administration could yet decide to follow through on the rhetoric.

Relations were chilled further in October, when the World Trade Organisation decided that the US could impose tariffs worth more than €7 billion on EU imports, after a 15-year-long legal case against Airbus subsidies wrapped up.

The WTO is expected to come to the same conclusion on a parallel case regarding US aerospace giant Boeing next year. Reciprocal action could trigger a tit-for-tat on more tariffs, although there are doubts that the car sanctions would not be WTO-compliant.

Trade concerns also stem from China, which has been the catalyst for much of the US president’s willingness to push the established multilateral world order to its limits.

China is the second most important destination for EU car exports, with a 17% slice of overall output. It is also attracting domestic investment: earlier in 2019, VW announced a multi-billion-euro punt on electric-car-building capacity there.

That decision drew short shrift from clean mobility advocates in Europe though, who criticised the Wolfsburg-headquartered marque for failing to make that investment at home.

Elon Musk’s Tesla has also set up shop in the Middle Kingdom, building one of its so-called gigafactories. Although still under construction, ‘Gigafactory 3’ is taking shape at record pace and has now been connected to the state’s electric grid.

Beijing could slap tariffs on US car imports as part of the ongoing commerce pact, so a domestic factory is seen as an elegant way around that eventuality. The works are estimated to be costing $2 billion.

The US firm is also on the hunt for a base for its European operations, after a strong debut year convinced management that the investment would pay off. Analysts also point out that cars built there might be safe from any reciprocal tariffs imposed by the EU.

Germany has emerged as a frontrunner in the race to host the mega-facility.

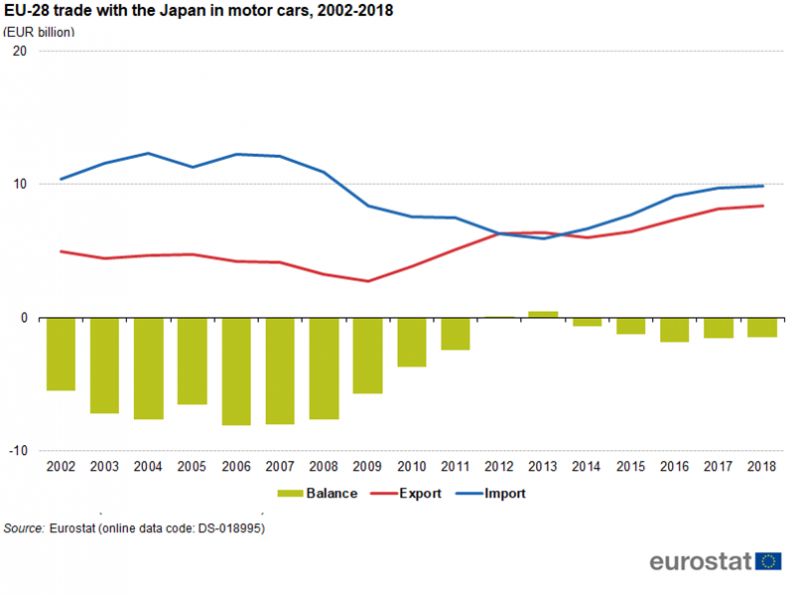

Despite the allure of its domestic demand though, China does not feature in the top five of importing automaker countries, which are headed by Japan.

In 2012-2013, EU car exports to Japan briefly overtook imports but that trend has since corrected itself. The stream of Japanese-built autos making their way into the single market is likely to increase thanks to the new EU-Japan free trade agreement.

The EU previously imposed a 10% import levy on cars but under the new pact, in force since February, that tariff will gradually decrease to zero over the course of the next eight years.

Another mega trade deal in the works is the Mercosur agreement with Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. ACEA welcomed the conclusion of talks in July, pointing out that the EU only exported 73,000 cars to those four countries in 2018, out of a total of 3.3 million new cars sold.

Cars are currently taxed at a rate of up to 35%, while car parts endure levies of up to 18%. If the agreement is implemented, Mercosur countries will remove those high duties. The deal will also ensure those countries accept vehicles that have secured licensing under UN-certified schemes.

DIGITAL MATTERS

Developments in the digital world will also have an impact on mobility going into the next decade. Issues like autonomous and connected cars will take centre stage, leading some analysts to already predict that OEMs will transition into data companies.

The issue of connected cars has already frustrated EU legislators. Earlier this year, the Commission proposed making WiFi the vector of choice, citing road safety as a pressing concern and alleging 5G technology is not advanced enough yet.

Plans are afoot to install sensors in new cars that will alert drivers to hazards like pedestrians and cyclists.

EU transport chief Violeta Bulc told EURACTIV that “WiFi is a proven technology and has almost no patents on it anymore. It’s available now, is easy to implement and it’s cheap.”

She also said that “We will issue a call for testing 5G but there is no product on the market today that we could test, set standards for or deploy. There is nothing on the market, will there be in two, three, four years? I don’t know. It’s too much of a gamble.”

The Slovenian official said that WiFi chips would allow pedestrians and cyclists to wear smart-clothing that would increase their visibility and, hopefully, decrease the number of road accidents.

However, Bulc was defeated by more than 20 EU Council members who argued that the proposal to make the system WiFi-only flouted the technological neutrality mantra of the Commission.

They also warned that putting all the EU’s eggs in one basket would make the road safety system outdated when 5G is up and running. There were also claims that newer systems would not be backward-compatible with the older versions.

After the Commission was asked to go back to the drawing board, Bulc told EURACTIV that the executive still favours WiFi but warned that a solution to the impasse is unlikely before the end of her mandate, likely to elapse in December.

The Commissioner does acknowledge that 5G technology has a role to play in transport though and that autonomous driving or self-driving cars should be the focus of companies pushing for the next-generation cellular network.

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) have been promised ever since the 1939 World’s Fair Futurama exhibit showed cars gliding along automated roads. There have been a number of technological breakthroughs since then but technical and regulatory obstacles remain.

AVs need testing and lots of it, in order to amass enough data for the software to learn the task it must fulfil. The UK recently announced that it would relax its rules so more demo projects can be trialled and MEPs are keen to embrace the trend.

Last year, lawmakers voted on a report that sought to make it clear that Europe wants to compete with the US and China on self-driving autos but there are still issues like liability assessments and data protection to wade through.

Tesla is again proving to be a pace-setter and is reportedly putting pressure on EU officials to relax the rules so its home-grown driving assist system is not limited by the law as it is.

Advocates of the technology say that AVs will reduce accidents, improve quality of life and make a contribution to fighting climate change, as software can be programmed to drive more efficiently.

Its detractors insist that it might increase accidents while the kinks are being ironed out and that the sector’s environmental impact would get worse, as AVs might incentivise car ownership.

The EU has at least begun to lay the groundwork for the infrastructure needed to support AV technology: its Galileo global positioning system is currently considered the most accurate available on the market and a key cog in rolling out self-driving vehicles.

Commission Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič told EURACTIV that “we’ll need it [Galileo] too when we’re thinking about self-driving and autonomous vehicles. The fact that Galileo is ten times more precise than GPS is going to help.”

Aside from regulatory hurdles, policy-makers will have to ensure a dialogue with urban planners and city officials about the use of space, as mobility strategies for the next decade are already firmly on the minds of all involved.

22 October 2019

Euractiv