Scientists Debate Role of Warming Arctic in Winter Deep Freezes

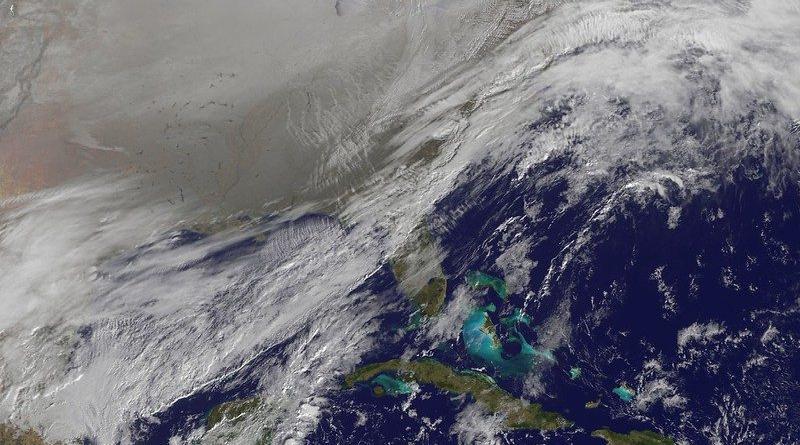

The millions of North Americans who found themselves shivering through late December’s bitter cold snap can surely thank a meandering polar vortex, but whether and how a rapidly warming Arctic might be involved in these intensifying deep freezes remains a subject of fierce scientific debate.

While it might seem counter-intuitive, the idea that a warming Arctic might be exacerbating periodic deep freezes in typically temperate latitudes has been around for a while.

“The evidence is only growing,” climate scientist Judah Cohen told the New York Times in the days leading up to the monster winter storm that left at least 90 people dead. Cohen, who works for Massachusetts-based weather-risk assessment firm Atmospheric and Environmental Research, has been studying the links between Arctic warming and the stratospheric polar vortex—a high-speed, circumpolar band of winds some 29 kilometres above the Earth’s surface—since 2005.

In a paper published last September in the journal Science, Cohen linked the devastating and deadly freeze that hit Texas in February, 2021, to Arctic warming by way of changes in stratospheric polar vortex circulation that are in turn being driven by increases in the amount of energy and moisture lower down in the troposphere.

Explaining his research in a September post in The Conversation, Cohen said these changes deliver a kind of “kick” to the troposphere, which responds by producing waves that then radiate upward into the stratosphere. He identified melting sea ice, and increased snow cover in Siberia, as key drivers of the shift.

Cohen believes it is these waves that are disrupting the stratospheric polar vortex, weakening and stretching it in ways that in turn make the polar jet stream, another band of high-speed circumpolar winds roughly eight miles up, weaker and wavier, and more inclined to meander further south, bringing with it Arctic temperatures.

Others are not so sure. “Unfortunately, the state of things is still ambiguous,” said University of Wisconsin climate scientist Steve Vavrus, who co-authored a groundbreaking 2012 paper postulating a connection between Arctic warming and changes to the polar vortex. “I wish I had a clear answer,” he told the Times.

Contributing to the present uncertainty, notes the Times, is the fact that “the short-term trends in cold extremes, jet-stream waviness, and other climate-related measurements in the 1990s and 2000s” may have been anomalous and caused by natural variability. According to research conducted by the University of Exeter and published in the journal Nature Climate Change in November, 2020, the trend fell out of sight between 2010 and 2019.

And then, even the billion-dollar deep freeze that hammered Texas almost two years ago “wasn’t unprecedented meteorologically,” explained Yale Climate Connections (YCC) meteorologist Bob Henson. “There have been cold waves on par with that every 30 or 40 years,” Henson said, in a recent interview with YCC.

While the debate surrounding the polar vortex and Arctic warming is “lively” and likely to continue, other markers of global heating are not in doubt, Henson added.

“I think what’s much more important in terms of climate change is what happens to our summers and what happens to heavy rainfall,” he said. More intense heat waves and downpours are getting more common, he noted, and “those kinds of events are definitely climate-change-driven.”