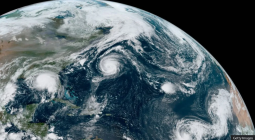

The Observer view on climate change: Hurricane Milton is a portent – but it’s not too late

The havoc unleashed by Hurricane Milton provided unambiguous evidence that we are entering a critical and alarming new phase in the planet’s climate crisis. Rising fossil fuel emissions have triggered increases in ocean temperatures and sea levels to such an extent they are generating some of the most destructive storms ever experienced in Florida. Together with Hurricane Helene earlier, the lives of about 250 people have been claimed and thousands of homes destroyed. Florida has been left reeling and forecasters have warned there is more to come – a lot more.

It is a grim prognosis that should be galvanising Florida’s political leaders into taking urgent action to protect the state. Extraordinarily, this has not been the case. Despite the intensification of hurricanes and worsening flooding over the past decade, governor Ron DeSantis has consistently rejected the idea that global warming poses a threat to Florida or that the phenomenon exists at all. A few weeks ago, he signed a law erasing the words “climate change” from state statutes and effectively pledged the state’s future to burning fossil fuels. Such behaviour is disturbing.

DeSantis is a Republican who is matched in the vehemence of his climate denials by his party’s candidate for the US presidency, Donald Trump. Should the latter triumph in next month’s election, the tribulations that afflict Florida will be escalated and repeated across the nation and the rest of the planet. Trump has vowed to dismantle the environmental policies introduced by President Joe Biden and promised to allow increases in the production of fossil fuels by drilling on public lands. In doing so, Trump would allow billions of tonnes of extra carbon to be pumped into our already overheated atmosphere and send a clear signal to other nations, which might be wavering in their commitment to the fight against global warming, that they need not bother to act.

Such an entirely plausible scenario would have grim implications for our already endangered planet. Global temperatures are close to reaching the 1.5C rise that the 2015 Paris agreement pledged to try to prevent. Today, a rise of 2C seems inevitable, with worse likely to follow. Jim Skea, the chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), recently warned the world was headed towards 3C warming by 2100 if current policies are maintained. In such an overheated world, several catastrophic points of no return would be passed, from the runaway melting of ice sheets to the Amazon rainforest drying out, on top of catastrophic sea-level rises and the displacement of millions of people whose homelands have become uninhabitable. Earth will become meteorologically and politically unstable.

It is an extraordinary situation made all the more alarming by the basic observation that we have known about these dangers for decades but have done little to impose measures that might deflect them. In a few weeks, politicians and scientists will meet at Cop29, the UN climate change conference, that will be held in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. The meeting should be an opportunity for world leaders to galvanise nations into action. This is unlikely, with most of the discussion expected to focus on methods by which developed nations can pay poorer countries to transition away from fossil fuels and adapt to climate change’s worst impacts. A commitment to end fossil fuel burning was agreed in principle at the last Cop, meeting but there has been little movement, say observers. Carbon emissions look set to continue for a long time.

This leaves the world with one last option. If we refuse to halt the burning of fossil fuels with sufficient speed, we must find ways to catch the resulting emissions as they are created or – further in the future – after they have reached the atmosphere. This means developing ways to extract carbon emissions at factories and power plants and then to sequester them. This is carbon capture and storage (CCS), a process that recently received a major boost in the UK when the energy secretary, Ed Miliband, announced a £22bn investment in CCS schemes that would eventually lead to 8.5m tonnes of carbon dioxide a year being removed from emissions from British industrial plants.

It should be noted that the UK emitted 384m tonnes of carbon dioxide last year, so the scheme will clearly make little difference to our overall contribution to global warming. However, it should, if successful, highlight a route for tackling the crisis by providing us with an additional weapon in the fight against global warming alongside renewable energy, electric cars and home insulation. From that perspective, Miliband deserves congratulation – though questions remain. Why should public money be spent on cleaning up emissions created by the fossil fuels that make private companies so much money, for example?

Crucially, we are failing to halt global warming. We are not going to stop carbon in the atmosphere reaching dangerous levels quickly enough and so will need to find ways to remove it once it has got there. We are going to need every weapon we can develop for this purpose if we are to deal with the greatest threat that faces civilisation today. The alternative is the global spread of the carnage that last week engulfed Florida.

Cover photo: By The Guardian