Methane emissions from gas flaring being hidden from satellite monitors

Oil and gas equipment intended to cut methane emissions is preventing scientists from accurately detecting greenhouse gases and pollutants, a satellite image investigation has revealed.

Energy companies operating in countries such as the US, UK, Germany and Norway appear to have installed technology that could stop researchers from identifying methane, carbon dioxide emissions and pollutants at industrial facilities involved in the disposal of unprofitable natural gas, known in the industry as flaring.

Flares are used by fossil fuel companies when capturing the natural gas would cost more than they can make by selling it. They release carbon dioxide and toxic pollutants when they burn as well as cancer-causing chemicals.

Despite the health risks, regulators sometimes prefer flaring to releasing natural gas – which is 90% methane – directly into the atmosphere, known as “venting”.

The World Bank, alongside the EU and other regulators, have been using satellites for years to find and document gas flares, asking energy companies to find ways of capturing the gas instead of burning or venting it.

The bank set up the Zero Routine Flaring 2030 initiative at the Paris climate conference to eradicate unnecessary flaring, and its latest report stated that flaring decreased by 3% globally from 2021 to 2022.

But since the initiative, “enclosed combustors” have begun appearing in the same countries that promised to end flaring. Experts say enclosed combustors are functionally the same as flares, except the flame is hidden.

Tim Doty, a former regulator at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, said: “Enclosed combustors are basically a flare with an internal flare tip that you don’t see. Enclosed flaring is still flaring. It’s just different infrastructure that they’re allowing.

“Enclosed flaring is, in truth, probably less efficient than a typical flare. It’s better than venting, but going from a flare to an enclosed flare or a vapour combustor is not an improvement in reducing emissions.”

The only method of detecting flaring globally is by using satellite-mounted tools called Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite of detectors (VIIRS), which find flares by comparing heat signatures with bright spots of light visible from space.

But when researchers tried to replicate the database, they saw that the satellites were not picking up the enclosed flares.

Eric Kort, an associate professor at the University of Michigan, said: “The VIIRS satellite database is still the standard product that scientists use globally. It’s the best, most consistent product we currently have.

“If you enclose the flare, people don’t see it, so they don’t complain about it. But it also means it’s not visible from space by most of the methods used to track flare volumes.”

Without the satellite data, countries were forced to rely mostly on self-disclosed reporting from oil and gas companies, researchers said. Environmentalists fear the research community’s ability to understand pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector could be jeopardised.

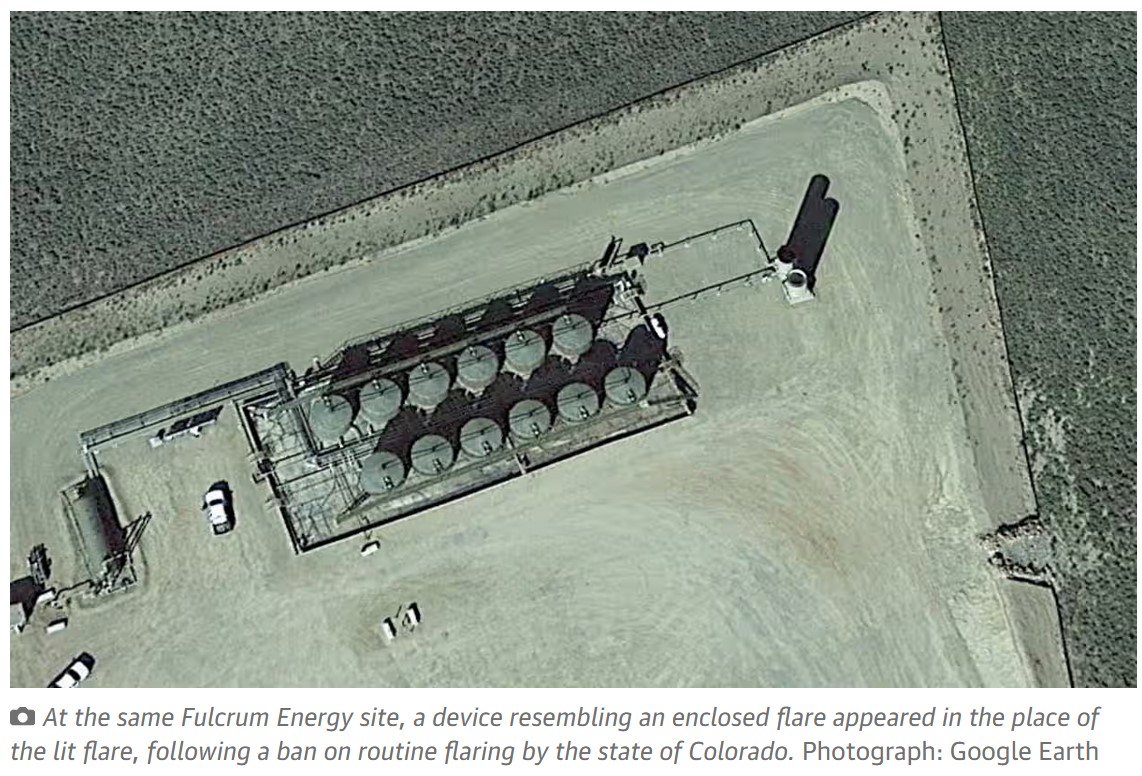

Colorado became the first and only US state to ban routine flaring in 2021. But Maxar satellite imagery shows enclosed flares replacing open-lit flares in the run-up to the Colorado ban on flaring, which provided a carve-out clause for enclosed flaring devices.

Google Earth historical images of one site in Jackson County, Colorado, show a lit flame disappearing and being replaced with an enclosed flaring device. Because the flaring within the site is not detectable, it is difficult for researchers to determine when it is burning and for what purpose.

The NGO Earthworks, with an optical gas-imaging camera usually used by industry specialists looking for emissions leaks, recorded footage showing invisible pollutants coming from the device. However, the site’s owner, Fulcrum Energy Capital Funds, told the Guardian it had eliminated flaring from its facilities.

Methane and carbon dioxide plumes were seen coming from enclosed flaring devices in the Four Corners region of New Mexico, according to satellite data from CarbonMapper, which provides publicly accessible data on greenhouse gases.

In November 2023, the EU announced a plan to phase out routine flaring as part of legislation designed to tackle methane emissions. But enclosed flares have started to appear in the EU, with information from oil and gas equipment supplier websites suggesting the devices are being sold in multiple member states.

Satellite images show enclosed flares at Ineos facilities in Grangemouth, Scotland, and the Ineos Rafnes refinery in Norway. In Germany, enclosed flares can be seen at facilities owned by the steel manufacturer ArcelorMittal.

An Ineos spokesperson said the enclosed flare “leads to significantly less noise being emitted and much lower luminosity”, adding that these things were important for communities living and working close to its sites.

An ArcelorMittal spokesperson said: “We installed an enclosed flaring device as a precautionary measure, so that the flare is not visible from a distance if gas had to be flared at night.” The device had a 100% combustion rate andno measurable emissions, the company added.

Zubin Bamji, the programme manager of the World Bank’s Global Flaring and Methane Reduction Partnership, said volumes from enclosed flares were “very small and are unlikely to have a significant impact on flare volume estimates at a regional, country or global level”, but confirmed that VIIRS did not classify enclosed flaring devices as flares.

A source with knowledge of upcoming EU methane legislation said it “covers all flares, not just those detectable by satellite”, and added that flaring in emergency situations would still be allowed.

It was not immediately clear how the EU would determine whether flaring inside enclosed flares was routine or for emergency situations.