Exposure of vulnerable to heat reached new record in 2019, says Lancet.

The fifth annual report on the climate crisis and human health also found millions of lives could be saved by tackling emissions and the Covid pandemic together.

Exposure of the most vulnerable people to extreme heat reached a record high in 2019, a new Lancet report has found.

Over the past two decades, there has been a 54 per cent increase in heat-related deaths in people over 65, the age group most vulnerable to heatwaves.

During the same time period, exposure to wildfires and their health impacts increased in 114 of 196 countries.

The findings come from the fifth Lancet Countdown report on the climate crisis and human health.

Each year, the report’s team of around 120 climate, health and policy experts track how global heating is affecting people’s health and wellbeing through 43 different indicators.

This year’s results are “the most concerning outlook for human health since the report’s inception”, Dr Ian Hamilton, a researcher at University College London and executive director of the report, told a press briefing held last week.

“Climate change-induced shocks are claiming lives, damaging health and disrupting livelihoods in all parts of the world right now,” he said.

“That means that no continent, country or community remains untouched. But the most vulnerable in our society bear the greatest burden, revealing a deeper question of justice and equity to our need to take action now.”

His words come as a UN report found that 2020 is likely to be one of the three hottest years on record, according to provisional data.

He added that the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change represent “two converging crises”.

“Ultimately we don’t have the luxury of tackling one crisis at a time,” he said.

“We see wildfires and extreme weather events have affected communities at the same time as the pandemic ... Unless a global Covid-19 recovery is aligned with the response to climate change, the world will fail to meet the targets laid out in the Paris Agreement.”

Tackling the climate crisis could also help to stop the emergence of new potentially pandemic-causing animal-borne diseases, he added.

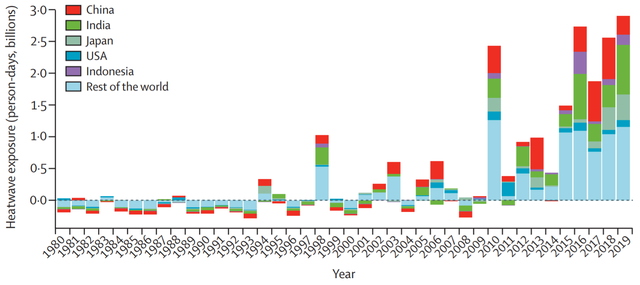

This year’s report found that vulnerable people faced an additional 475m heatwave exposure events in 2019 — beating a previous record made in 2016. (“Exposure events” are defined as the number of days in which vulnerable people were exposed to extreme heat.)

(Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change (2020))

Exposure to extreme heat leaves people vulnerable to early mortality, heat stress, kidney failure and stroke, said Dr Hamilton.

“As societies age and as our globe warms, these are going to be two compounding impacts,” he added.

For the first time this year, the report has tracked the health of those who have been displaced or forced to migrate as a result of the climate crisis.

“People on the move are another vulnerable group,” said Dr Sonja Ayeb-Karlsson, a senior author of the Lancet Countdown report and senior research at the United Nations University in Tokyo, Japan.

The report found that, without intervention, between 145 and 565 million people living in coastal areas today will be affected by rising sea levels in the future. Many of these people may be forced to migrate in order to adapt to the impact of rising sea levels on health, the report says.

The report also tracked the links between diet, health and the climate crisis for the first time this year.

It found that “increasingly unhealthy diets are becoming more common worldwide” and that “excess red meat consumption” contributed to nearly one million deaths in 2017.

As well as contributing to health problems, excess red meat consumption is a driver of the climate crisis, the authors said.

This is because livestock production is particularly polluting. A study published in 2018 found the carbon footprint of animal-based foods is around 10 to 50 times larger than that of plant-based foods.

Commenting on this year’s report, Prof Philip Staddon, principal lecturer at the Countryside and Community Research Institute at the University of Gloucestershire, said: “This is a very thorough and detailed account of the health impacts of climate change, although maybe overly rich-world focused.

“The rich world will have the resources to cope with these predicted changes and mitigate them much better than the global south. For many poorer countries, the health impacts of climate change will be nothing short of a calamity.”

3 December 2020

INDEPENDENT