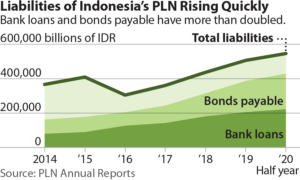

In a deepening debt hole of $34 billion, Indonesia’s PLN must stop digging.

The utility has added IDR100 trillion in debt annually for the last five years

Utilities globally started changing the way they do business years ago, but Indonesia’s PLN power company stands out as a laggard, focused on a confused menu of piecemeal generation options rather than holistic planning that provides system-level solutions, finds a new report from IEEFA, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

PLN, alongside utilities worldwide, has suffered a severe drop in revenue as power consumption fell by as much as 20% in some cases amid the COVID-19 pandemic, writes Elrika Hamdi, author of the report Never Waste a Crisis – Indonesia’s PLN Needs A Coherent Strategy to Ride Out the COVID-19 Pandemic.

“But the roots of PLN’s problems are deeper than just the pandemic: PLN’s quiet crisis reflects dysfunctional planning and governance that have put the company into strategic paralysis, unable to change direction or adapt to new market realities,” says Hamdi.

“Despite all the warning signs, senior managers still run the power sector with an old-fashioned business-as-usual mindset. Unfortunately, a 2010 playbook will not save PLN from falling deeper into a modern-day debt trap. Neither will indulging an extractive economy mindset that fosters dependence on fossil fuel, just because it’s there”.

“There has to be a willingness to ask the hard questions when PLN’s ocean of red ink proclaims that PLN’s resource-driven development plans are obsolete in a high-technology world.”

The report notes that much of PLN’s current predicament stems from a plan to add a massive 35 gigawatts of generation capacity to Indonesia’s power supply that was poorly designed and implemented.

“The 35 GW program is a political promise that was meant to embody President Joko Widodo’s (Jokowi’s) ambition to fully electrify Indonesia. There is nothing wrong with the ambition, but the subsequent planning and execution has lacked accountability,” says Hamdi.

“Adding generation capacity has become a goal with little attention paid to long-term financial impacts or new system design options. In the absence of much-needed checks and balances, PLN has been driven to the brink and taxpayers will be left to pay the price.”

“PLN’s ability to sustain debt at this level rests firmly on Indonesia’s investment-grade sovereign credit rating and the government’s readiness to support PLN debtors in the event of financial distress,” says Hamdi, noting that PLN bonds are still relatively attractive to investors because of the company’s monopoly and its quasi-sovereign status.

The author also questions the accountability of government support for PLN. Noting both direct and indirect supports, including subsidies, compensation, capital injections, special accounting treatments and government guarantees, Hamdi says there appears to be little consistent oversight of how government support is used to dress up PLN’s accounting.

“The Ministry of Finance, considering PLN’s strategic importance, makes PLN a top priority, but that does not mean PLN’s financial problems can be effectively addressed by endless access to cheap debt that could eventually threaten Indonesia’s financial credibility,” she concludes.

“The best strategy for PLN would be to rebase their planning framework to focus on more cost-effective grid investments that improve the long-run efficiency of the whole power system. Private sector players cannot invest in the grid and have therefore crowded into the generation sector. This has accentuated PLN’s narrow focus on baseload generation has resulted in excess capacity and a brittle system that lacks flexibility. What’s needed now is a more grid-centric strategy that would permit PLN’s investment to enable a more efficient system. It is crucial for PLN to make sure that the power sector reform is not just cosmetic.”

3 September 2020

IEEFA