Cities Are Our Best Hope for Surviving Climate Change.

The hysteria about urban density that arrived with the coronavirus is—like the pandemic itself—already easing. Regardless of how quickly or slowly urbanites return to their cramped apartments, however, the long term trend is clear. Humans will continue to flock to cities. And that’s a good thing, because if we want to survive the next, much bigger crisis on the horizon, cities are our best bet.

Cities currently consume two-thirds of the global energy supply and generate three-quarters of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions. Luckily for human civilization, they’re also extraordinarily motivated to minimize their cost to the climate—and quickly. Because cities are uniquely vulnerable to climate change, they’re also likely to be remade the fastest by the human need to survive and eventually thrive on a warmer planet.

Mayors and city managers across the world are turning urban centers into laboratories, implementing measures to cut air pollution and move toward zero-carbon energy. In some places, they’re reimagining the entire urban fabric to be greener, more efficient, and more resilient to the effects of climate change already being felt.

Step 1: Reconfigure

One of the most-discussed ideas in city design today is the so-called 15-minute city. The concept is simple: If people live within a short distance by foot, bike, or public transit of everything they need—schools, health centers, parks, grocery stores, and especially jobs—then they’ll rely less on cars.

It’s a tactical approach to urban planning that involves reclaiming streets for pedestrians and cyclists, boosting public transit systems, and creating mixed-use spaces. Each piece of the puzzle addresses a different aspect of the climate crisis. Nothing is terribly expensive, but no detail is too small.

Paris has gone the furthest toward realizing this urban ideal citywide, restricting the most polluting vehicles from entering the capital and banning all cars near the River Seine, with plans to reclaim more streets and turn parking lots into green spaces. But aspects of the 15-minute city have already been implemented all over the world.

Barcelona, for instance, has freed up entire swaths of the grid to make pedestrian “superblocks,” keeping noise and air pollution away from residents while also encouraging them to walk and cycle.

The Sant Antoni superblock used to be a four-lane crossing between Comte Borrell, Manso, and Paral·lel streets. The street was closed to autos, resurfaced to better absorb rainwater, and landscaped to mitigate heat.

A 2017 study on another superblock in the Gràcia neighborhood found that walking had increased in the area by 10% and cycling by 30% compared to 10 years earlier. Driving in the superblock had fallen by 26%.

The city plans to carve another one out of 21 streets by 2030. Achieving its ultimate goal of making 503 superblocks by 2050 could prevent as many as 667 premature deaths from air pollution each year.

About 250 European cities have created low-emission zones, where the operation of polluting vehicles is restricted or regulated to curb air pollution. In Lisbon, air quality improved significantly after the first measures to limit traffic in the city center were implemented a decade ago. Concentrations of fine particulate matter fell by about 30% from 2009 to 2016, according to researchers.

Street trees—another key feature of the 15-minute city—help reduce air pollution by absorbing CO2. But more important, they also mitigate the urban heat island effect by providing shade and releasing moisture into the air.

The ground isn’t the only place for greenery. In Chicago, rooftop vegetation proliferated after a 2004 mandate required private developments to include sustainable elements to qualify for assistance from the city. Then a 2015 zoning ordinance gave developers economic incentive to cover at least half of the roofs on new buildings with plants.

Step 2: Extend

The 15-minute city remains controversial for its potential to exacerbate inequality. London’s effort to create low-traffic neighborhoods, for instance, has drawn criticism from activists who say banning cars in well-off areas diverts traffic to neighborhoods near major roadways, which are less desirable and therefore tend to be home to marginalized populations.

Robust public transit is key to extending the benefits of the 15-minute city beyond the city itself—though what qualifies as “robust” will vary from place to place. Bogotá’s bus rapid transit system is already one of the world’s most heavily used, carrying 2.4 million passengers daily. With all those passengers, however, comes crowding.

To reduce congestion, the city plans to build 280 new kilometers of bike lanes over the next four years, in addition to the 550km that already exist. The goal: raise the proportion of overall trips by bike and scooter to 50%. Already, 7% of trips happen by bike, a higher share than in any other Latin American city.

The city is also offering tax incentives to businesses that invest in parking spaces for bikes at their establishment. Currently there are 16,000 bike parking spots in the city.

Bogotá’s whole public transit system—including its nearly 1,500 buses—is on track to be fully electric by mid-2022.

Step 3: Streamline

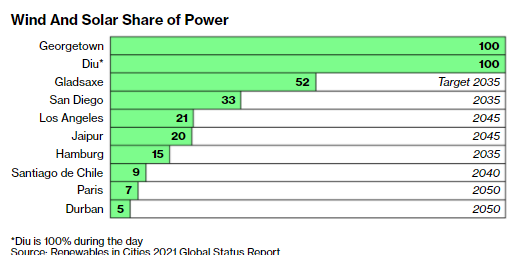

Cars tend to be the focus of urban sustainability efforts, but energy is a much bigger source of greenhouse gas emissions. While some cities are already getting all of their energy from renewable sources, most are still working on it.

Buildings alone account for more than half of a city’s emissions on average. Fully decarbonizing means replacing inefficient heating and cooling systems, which are, in turn, responsible for more than half of a building’s energy use. With that goal in mind, New York City instituted one of the U.S’s most stringent building codes, the result of a 2019 law mandating that all buildings of more than 25,000 square feet cut their carbon emissions 40% by 2030. That means 50,000 existing buildings will need to be retrofitted, creating a $20 billion renovation market, according to the Urban Green Council.

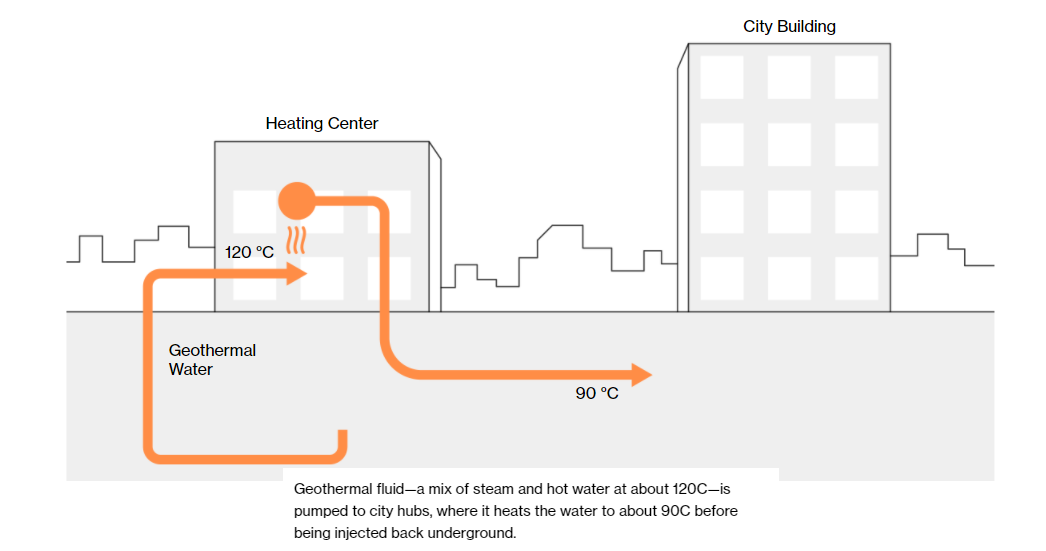

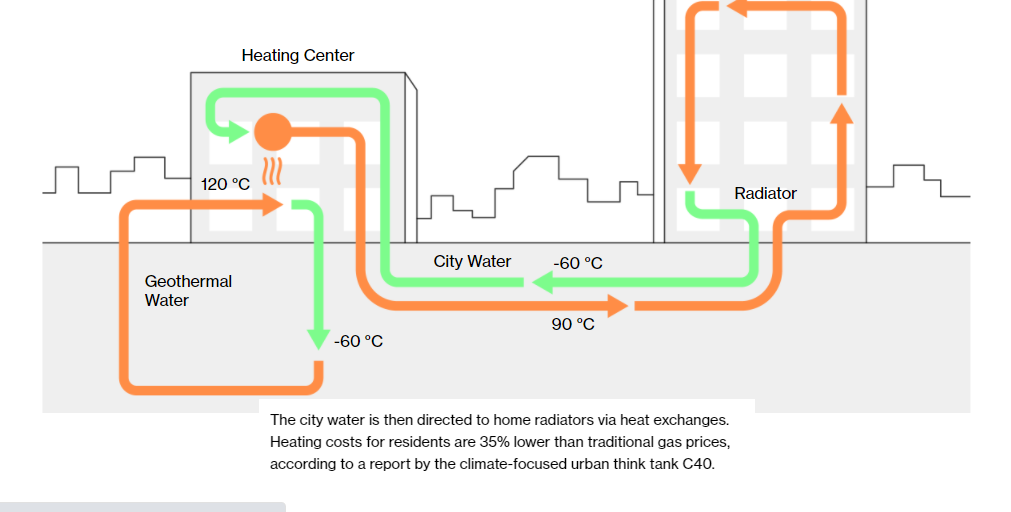

Increasing efficiency can also mean going beyond individual buildings. Districtwide climate control systems work by sending steam or chilled water from a central underground plant to multiple buildings via networks of pipes, potentially replacing millions of heating and cooling units. In Turkey, Izmir has been heating the Balçova-Narlidere district using geothermal energy since 1996.

The system has cut carbon dioxide emissions by about 110,000 metric tons per year—as much as the electricity used by 18,000 homes—while levels of airborne sulfur dioxide have plummeted.

Step 4: Protect

The more ambitious the solution, the greater the cost. Take so-called sponge cities, such as Chongqing, which use a mix of green space and underground storage tanks to absorb rainfall and prevent floods. In 2015, China’s government declared that 80% of cities should have sponge capabilities by 2030, at a cost of between 100 million RMB and 150 million RMB ($15.4 million to $24 million) per square km, according to the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development.

Among all the ways a city can pour money into climate defense, seawalls are perhaps the most notorious. Rotterdam—which could see water levels a full meter higher by 2100, putting 15,000 properties at risk—had a climate budget of €3.5 billion ($4.2 billion) last year, with most of it going to keep rising waters at bay.

Meanwhile, Venice’s mile-long flood barriers are designed to hold back the acqua alta, or high water that’s flooded the city intermittently for 1,200 years. They’re expected to be fully operational later in 2021, but have already been deployed.

The system’s 78 hydraulic gates, spread out over the three waterways that connect the Venetian Lagoon to the Adriatic Sea, are designed to hold back waters as high as 3m above normal.

After a decade of delays and corruption scandals, the barriers rose for the first time on Oct. 3, 2020, shielding the city from a 135cm high tide that would have flooded half its surface area.

Two months later, the barriers failed to rise due to a forecasting error, drowning St. Mark’s Square and leading to a fresh wave of controversy over the project’s $8 billion price tag.

No amount of money or concrete will hold back the waters forever, though. Beira, the fourth-largest city in Mozambique, received a $120 million World Bank loan in 2012 to build an 11 kilometers of canals and drains to absorb high swells from major storms.

Seven years later, Cyclone Idai made landfall close to the city, bringing heavy rainfall, winds stronger than 150 kph, and about a 2m storm surge. About 90% of the city’s area was destroyed, according to Red Cross and Red Crescent estimates—including the storm barriers. All told, the storm killed more than 1,000 people.

Cyclone Idai Hit Beira, Mozambique in 2019

So What Now?

Trying to stop the forces of nature is a losing battle. Last year—either the second-warmest or the warmest year on record, depending on whom you ask—the world incurred $210 billion in weather-related damages, up from $166 billion in 2019. Nine of the 10 hottest years have occurred since 2010. Based on that trend, those damage figures are only going to rise.

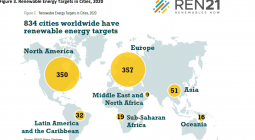

Keeping climate change under control, however, is for the most part still possible. At least 105 cities, home to 170 million people worldwide, have made major progress in setting climate targets and laying out adaptation plans since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, according to the nonprofit CDP. In one optimistic projection, current technology and low-carbon measures could enable cities to cut emissions by almost 90% by 2050.

*read the original article here

21 April 2021