Brazilian Amazon Has Lost Millions of Wild Animals to Criminal Networks, Report Finds

By Sharon Guynup

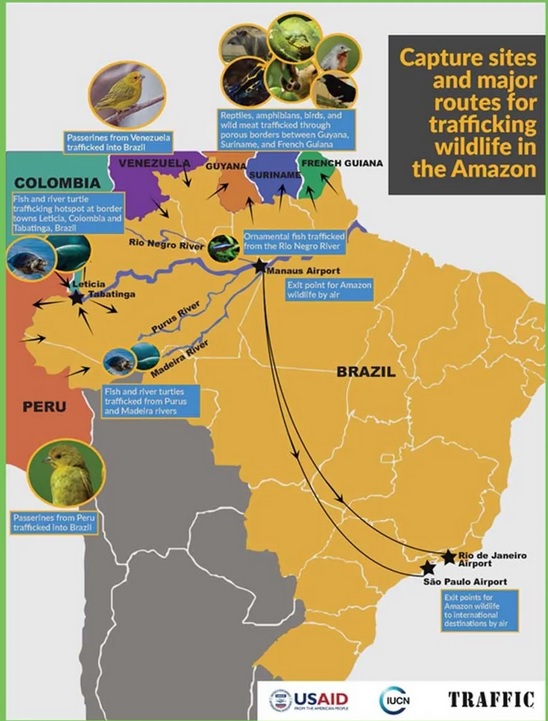

The Brazilian Amazon is hemorrhaging illegally traded wildlife according to a new report released Monday. Each year, thousands of silver-voiced saffron finches and other songbirds, along with rare macaws and parrots, are captured, trafficked and sold as pets. Some are auctioned as future contestants in songbird contests. Others are exported around the globe.

Fish bound for ornamental home aquariums also pour out of the Amazon, including the tiny, iridescent blue and red cardinal tetra. Arapaima fish — also known as pirarucù, one of the world's largest freshwater fish — are caught illegally, "laundered" amidst captive-bred specimens and shipped to the U.S. in large numbers.

Other fish are headed for the dinner table, as are freshwater turtles and their eggs, while tapir, peccary and other mammals are sold in Brazil as bushmeat. Jaguar teeth, heads and skins are shipped to China.

Millions of animals are being illegally captured and traded live and in parts in a thriving Brazilian black market, according to the report, produced by TRAFFIC, a UK-based nonprofit that studies the trade. "The pervasive and uncontrolled capture of wild animals and plants for the illegal trade is having grave consequences for Brazilian biodiversity, the national economy, the rule of law and good governance," it says.

Lack of Data Hides Trafficking

Deep-dive research by biodiversity consultant Sandra Charity — who wrote the 140-page study with Juliana Ferreira, executive director of the nonprofit conservation group Freeland Brasil —focused on Amazon rainforest species and closely investigated the domestic bird trade.

Importantly, the researchers found that an ever-increasing segment of the illegal trade launders poached animals via a sprawling, legal captive breeding industry — a network that specializes in birds, which have a huge domestic market in Brazil.

The authors also discovered that few government agencies have kept records or reported solid data that quantify the true scope of the problem. In many cases, records did not even identify the species or number of animals seized by authorities, while data coming from the Amazon was "notoriously scarce."

"Significant seizures are made on a daily basis by Amazon state law enforcement, and we did not have access to their data," Ferreria said, adding, "from what we saw, [the illegal trade] is even bigger than we imagined."