Biden plans to fight climate change in a way no U.S. president has done before.

Joe Biden is preparing to deal with climate change in a way no U.S. president has done before – by mobilizing his entire administration to take on the challenge from every angle in a strategic, integrated way.

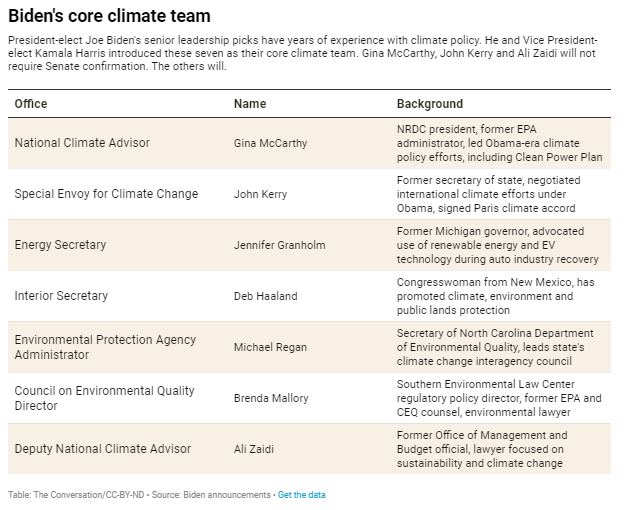

The strategy is evident in the people Biden has chosen for his Cabinet and senior leadership roles: Most have track records for incorporating climate change concerns into a wide range of policies, and they have experience partnering across agencies and levels of government.

Those skills are crucial, because slowing climate change will require a comprehensive and coordinated “all hands on deck” approach.

We did that with energy when I was governor of Colorado, and I can tell you it isn’t simple. Energy policy isn’t just about electricity. It’s about how homes are built, how they generate power and feed it into the grid and how the transportation, industrial and agriculture sectors evolve. It’s about regulations, trade rules, government purchases and funding for research for innovation. Coordination and collaboration among agencies and different levels of government is crucial.

A coordinated approach also helps ensure that vulnerable populations aren’t overlooked. Biden has committed to help disadvantaged communities that have too often borne the brunt of fossil fuel industry pollution, as well as those that have been losing fossil fuel jobs.

The Biden-Harris team’s depth of experience will be vital as they take over from a Trump administration that has been stripping government agencies of their expertise and eliminating environmental protections. With Democrats gaining control of both the House and Senate, the Biden administration may also have a better chance of overhauling laws, funding and tax incentives in ways that could fundamentally transform the U.S. approach to climate change.

Here are some of the biggest challenges ahead and what “all hands on deck” might mean.

Dealing with all those climate policy rollbacks

From its first days, the Trump administration began trying to nullify or weaken U.S. environmental regulations. It had rolled back 84 environmental rules by November 2020, including major climate policies, and more rollbacks were being pursued, according to a New York Times analysis of research from Harvard and Columbia law schools.

Many of these rules had been designed to reduce climate-warming pollution from power plants, cars and trucks. Several reduced emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from oil and gas production. The Trump administration also moved to open more land to more drilling, mining and pipelines.

Some rollbacks have been challenged in court and the rules then reinstated. Others are still being litigated. Many will require going through government rule-making processes that take years to reverse.

Pressuring other countries to take action

Biden can quickly bring the U.S. back into the international Paris climate agreement, through which countries worldwide agreed to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions driving global warming. But reestablishing the nation’s leadership role with the international climate community is a much longer haul.

Former Secretary of State John Kerry will lead this effort as special envoy for climate change, a new Cabinet-level position with a seat on the National Security Council. Other parts of the government can also pressure countries to take action. International development funding can encourage climate-friendly actions, and trade agreements and tariffs can establish rules of conduct.

Cleaning up the power sector

The Biden-Harris climate plan aims to cut greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector to net zero by 2035.

While 62 major utilities in the U.S. have set their own emission reduction goals, most leaders in that sector would argue that requiring net zero emissions by 2035 is too much too fast.

One problem is that states are often more involved in regulating the power sector than the federal government. And, when federal regulations are passed, they are often challenged in court, meaning they can take years to implement.

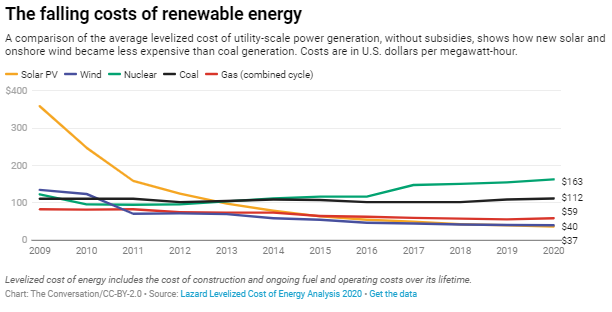

Reducing greenhouse gases also requires modernizing the electricity transmission grid. The federal government can streamline the permitting process to allow more clean energy, like wind and solar power, onto the grid. Without that intervention, it could take a decade or more to permit a single transmission line.

Chart: The Conversation/CC-BY-2.0 Source: Lazard Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis 2020 Get the data

What to do about vehicles, buildings and ag

The power sector may be the easiest sector to “decarbonize.” The transportation sector is another story.

Transportation is now the nation’s leading emitter of carbon dioxide. Decarbonizing it will require a transition away from the internal combustion engine in a relatively short amount of time.

Again, this is a challenge that requires many parts and levels of government working toward the same goal. It will require expanding carbon-free transportation, including more electric vehicles, charging stations, better battery technology and clean energy. That involves regulations and funding for research and development from multiple departments, as well as trade agreements, tax incentives for electric vehicles and a shift in how government agencies buy vehicles. The EPA can facilitate these efforts or hamstring them, as happened when the Trump EPA revoked California’s ability to set higher emissions standards – something the Biden administration is likely to quickly restore.

The other “hard to decarbonize” sectors – buildings, industry and agriculture – will require sophistication and collaboration among all federal departments and agencies unlike any previous efforts across government.

A new comprehensive climate bill

The best way to tackle these sectors would be a comprehensive climate bill that uses some mechanism, like a clean energy standard, that sets a cap, or limit, on emissions and tightens it over time. Here, the problem lies more in the politics of the moment than anything else. Biden and his team will have to convince lawmakers from fossil fuel-producing states to work on these efforts.

Democratic control of the Senate raises the chances that Congress could pass comprehensive climate legislation, but that isn’t a given. Until that happens, Biden will have to rely on agencies issuing new rules, which are vulnerable to being revoked by future administrations. It’s a little like playing chess without a queen or rooks.

Years of delays have allowed global warming to progress so far that many of its impacts may soon become irreversible. To meet its ambitious goals, the administration will need everyone, progressives and conservatives, state and local leaders, and the private sector, to work with them.

12 January 2021

THE CONVERSATION