Amid the battle of Xi Jinping and Joe Biden, a new global order struggles to take shape

While the US and China vie for supremacy, smaller countries, championed by Barbados PM Mia Mottley, are speaking out on key challenges of climate, poverty and migration

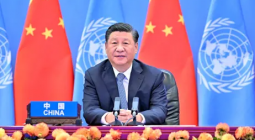

Competition for pole position in the race to boss the 21st century’s fast-evolving new world order is hotting up. US president Joe Biden sought a winning strategic partnership with Narendra Modi’s India. The EU unveiled an economic security strategy to fend off Chinese and Russian predators. In Beijing, Xi Jinping told America’s top US diplomat who’s in charge: China.

In Paris, meanwhile, leaders of the global north and south planned a new beginning. The aim: to deliver billions in funding, promised at last year’s Cop27, to help vulnerable countries fight the climate crisis and related poverty, inequality and debt. Poorer nations urge radical reform of the global institutional framework, which they say has failed.

It was a busy week. Yet why all the haste? It seems recent crises have convinced states that things cannot continue as they are. The pandemic’s impact, the Ukraine war, the accelerating climate crisis and the cost of living crunch, including energy, food supply and inflation shocks, are driving an urgent rethink about how the world will work – and who will run it – in the coming decades.

A rare moment of seismic transformation may have arrived, not unlike 1945 after the defeat of fascism, or 1991, when the Soviet empire collapsed. Faith in the western neoliberal model and the unfettered, free-market capitalism associated with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher is eroding. Subsidies and state intervention are back in vogue. Globalisation is in retreat. The unheard demand a hearing.

Respect for the UN and the international rules-based order is palpably weakening. A deadlocked security council teeters on irrelevance. Global regulatory systems, represented by the IMF, World Bank and World Trade Organization, are not fit for purpose in the view of developing countries. UN-led peacekeeping and conflict resolution appear ineffective.

The long-term geopolitical and security implications of this shifting ideological and structural environment are huge and destabilising. The American approach, shaped by Biden and Jake Sullivan, his national security adviser, is to maintain supposedly benign US global leadership while ensuring foreign policy serves the domestic, economic interests of America’s “middle class”.

That means, for example, no more free trade agreements resulting in the “export” of American jobs and investment to lower-wage, lower-tax economies – and sanctions on countries that oppose American aims. Donald Trump’s ascent in 2016, like rampant European rightwing populism, was fuelled by perceived declines in working people’s incomes, security and life chances. Biden seeks to reverse that.

This is where last week’s White House tryst with India’s prime minister comes in. Biden offered Modi deals on defence and technology, and heaps of flattery. This is not because the US has suddenly conceived a sincere affection for India’s Hindu nationalist leader, notorious for abuses of human rights and media freedom.

It’s because Biden wants Modi’s help in containing China economically and militarily – and sustaining American pre-eminence. Apparently, it’s the cost of doing business in the race to rule the world.

Xi, another serial rights abuser, has his own vision of a 21st-century world order. Naturally it, too, places him on top of the pile. China was globalisation’s big winner. Now its economy is stumbling and its international posture, typified by sabre-rattling over Taiwan and aggressive debt diplomacy, is backfiring. But Xi, newly installed as de facto president for life, is doubling down.

Xi’s world order is based on non-interference in other states’ internal affairs – meaning a country’s lack of democracy or internal repression are its business and no one else’s. Basically, it’s a tyrant’s charter – and as such, anathema to the west. No wonder Antony Blinken, US secretary of state, felt so uncomfortable visiting Beijing last week. Although Blinken secured a meeting with Xi, China’s leader declined to sit next to him, preferring to talk down from a distance. The visit achieved nothing of substance – while underscoring the ideological gulf. Then Biden put his foot in it, calling Xi a “dictator” in a sudden burst of honesty.

Beijing’s efforts to remake the world in its authoritarian image help explain the EU’s first-ever economic security strategy. It entails new controls on sensitive technology and military exports, outsourcing and inward investment. It’s part of a bigger effort to build autonomy and resilience in an increasingly lawless world while reducing Europe’s dependencies, highlighted by Russia’s energy blockade. China is the strategy’s principal target.

Must the 21st century, like the second half of the 20th, inevitably be bipolar? A truly multipolar world could be safer, fairer and potentially more widely beneficial. Yet this involves a concept unfamiliar to American and Chinese presidents, other than in the Northern Ireland context – namely, power sharing.

But the dynamics are shifting. Medium-sized countries such as Brazil, Nigeria, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and Turkey are demanding a bigger say in global affairs and some have leverage to match. Weaker countries are making their voice heard, too, on the existential issues of climate, poverty, conflict and migration. They say time is running out – and they are right.

These countries have found an impressive champion in Mia Mottley, prime minister of Barbados. Mottley backs a transformational approach to climate challenges and global development involving a historic redistribution of wealth to poorer nations. It’s a big break with the old ways. Yet the old ways are badly broken.

What manner of new global order will ultimately emerge? It’s plain the old great-power games are unsustainable when the planet’s on fire, the ice is melting – and existing rules are ignored. To survive, let alone prosper, in the 21st century, the world needs to replace nationalistic, zero-sum rivalries and power blocs with a more equitable, genuinely multipolar dispensation.

In short, political leaders need the courage to change. It may sound improbable. But as the saying goes, everything is possible if you work for it.

Photograph: Stevens Tomas/ABACA/Shutterstock - Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados, meets French president Emmanuel Macron at the global finance summit in Paris last week.