Winter-less Olympics? 20 out of 21 cities that hosted Games could soon be too hot for events

Average February daytime temperature in host cities has jumped from 0.4C at events in the 1920s–1950s, to 6.3C this century

On a rapidly-heating planet is there a future for a global event whose premise is the availability of snow and ice?

That is the question posed by a new study which explores how Winter Olympics host cities will be impacted this century by global temperature rise under low and high emissions scenarios.

A research team, led by the department of geography and environmental management at the University of Waterloo in Canada, also asked elite athletes and their coaches how the effects of the climate crisis were impacting their disciplines.

“Our sports are going to end unless there is serious change in the world,” one athlete responded.

The study, published this month in the journal Current Issues in Tourism, is a timely insight into the relatively unexplored interplay of climate change and a burgeoning global sports tourism industry which researchers estimate could top $1,800 billion by 2030. The 2022 Beijing Olympics begin next week, the first time events will be run entirely on artificial snow.

Winter is warming and lasting for fewer days in many parts of the world. The average February daytime temperature in Winter Olympics host cities has jumped from 0.4C at events in the 1920s–1950s to 6.3C this century.

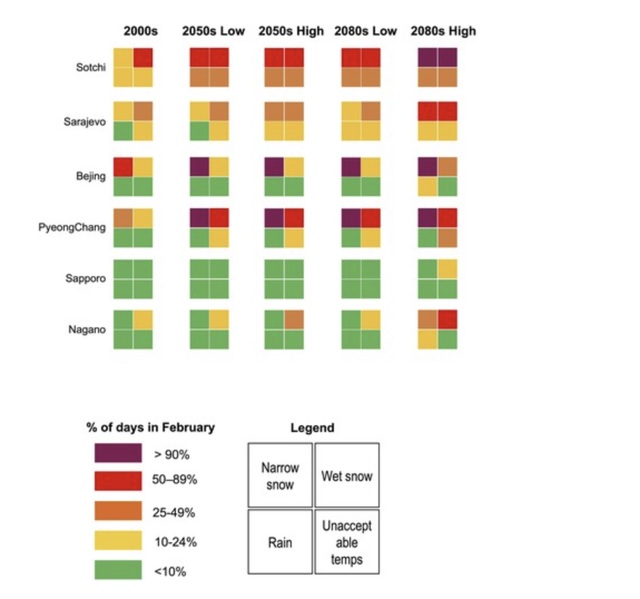

The new study found that under the current, global trajectory of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, only four out of 21 Winter Olympic host cities would have reliably cold conditions in 2050 - Lake Placid, New York; Lillehammer and Oslo in Norway; and Sapporo, in the mountainous northern Japanese island of Hokkaido.

By the end of the century, only Sapporo would be a reliable location.

However if global GHG emissions are slashed in line with the Paris Agreement, then the future of winter sports competitions looks more optimistic. Nine cities would remain reliable Winter Olympics hosts by about 2050, and eight in the late 21st century.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has partnered with the United Nations and organisations like World Rugby, Formula One, and FIFA on a “Race to Zero” initiative to bring international sports, which are carbon intensive in terms of travel and infrastructure, in line with the Paris’s science-based targets.

Ahead of Cop26 in Glasgow, the IOC announced it would be “climate positive” in 2024 by reducing direct and indirect emissions by 30 per cent and compensating more than 100 per cent of its remaining carbon footprint via offsets in its “Olympic Forest project.”

All Olympic host cities this decade have committed to be climate neutral. The 2024 Olympics in Paris aims to be the first “climate positive” Game

In the 100 years of modern Olympic history, both the summer and winter games have been subject to extreme weather events. The Tokyo Games, which were delayed to summer 2021 due to the Covid pandemic, were impacted by extreme heat and tropical storm rains. Temperatures soared to 35C , with 70 per cent humidity, creating risky conditions for both Olympians and spectators

In 2014, Sochi, Russia was the hottest ever place to host a Winter Olympics. The study highlighted earlier research which found higher crash and injury rates among Olympians and Paralympians, were partially attributed to higher ambient temperatures and lower quality snow conditions.

The study surveyed 339 athletes, including former and aspiring Olympians, and coaches from 20 countries across disciplines including in Alpine, Nordic, and freestyle skiing, ski-jumping and snowboarding.

“As we plan for the future of the Olympic Winter Games under accelerating climate change, an important perspective that has been missing from the limited research is that of the most important stakeholders – the athletes themselves,” the researchers said.

They were asked what they considered to be fair and safe conditions for competitions around four climatic indicators: unacceptably high or low temperatures, rain, wet snow, and poor snow coverage.

In terms of peak performance, those surveyed rated hardpack snow, injected surfaces (where the course or jump is injected with water ahead of the event so the snow freezes solid overnight), and hard icy surfaces as the most ideal conditions.

Low and thin snow cover were rated the most unacceptable, followed closely by fog, narrow snow coverage and rain. Cancelled training runs and last-minute changes to courses were also deemed most unacceptable.

“Too warm is the worst because it makes the course super slushy, the speed slows down, and you get a bunch on bomb holes in the landings which are unsafe!” one freestyle athlete told the researchers.

A Nordic Biathlon athlete responded: “Competing in too warm conditions can cause overheating, spiking the heart rate and internal body temp to an unhealthy status, also causing long term damage.”

Athletes and coaches were asked to identify acceptable and unacceptable temperature ranges for competition.

More than half responded that temperatures colder than −20C or warmer than 10C were unacceptable for safe and fair events. The ideal temperatures were between −10C and −1C.

Respondents were almost unanimous, at 94 per cent, in their fear that the climate crisis jeopardises the future of winter sports.

The study underlined the responsibility that international sporting bodies have towards athletes and their safety and the sector comes to grips with climate impacts.

One athlete noted that future Olympics events in a hotter world means that there is “risk that comes with competing in those temperatures and the effects on the body/mind”.

But they added: “Who’s going to qualify for the [Olympic] games and then sit it out?”

Louise Boyle Senior Climate Correspondent, New York

cover photo:

The Olympic rings at the National Alpine Skiing Centre in Yanqing, China. The 2022 Winter Olympics will run entirely on fake snow

REUTERS