Trophy hunter killings spark fierce battle over the future of super tusker elephants

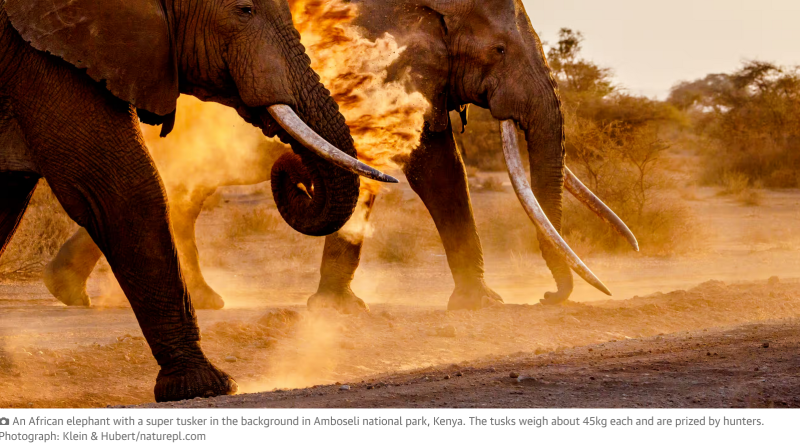

In the borderlands of Tanzania and Kenya, the “super tuskers” roam. A combination of old age, genetic pooling and prolonged protection from poaching has created a population of bull elephants with enormous tusks, weighing up to 45kg apiece, large enough to scrape along the ground as the animals walk. To many, the bulls are “living icons” of the African savannah. They are also highly prized by trophy hunters.

Now, a series of super-tusker killings has sparked a bitter international battle over trophy hunting and its controversial, sometimes counterintuitive role in conservation. Some conservationists believe the killing of these extraordinary animals should not be allowed. Others say controlled, regulated hunting can actually contribute to elephants’ long-term survival by providing jobs for local people and incentives for habitats to be preserved.

The conflict began brewing last year, when the Tanzanian government ended a 30-year informal agreement with Kenya by allowing hunters to legally shoot at least two out of the 10 remaining super tuskers. The herd is a cross-border population that migrates between Kenya (where trophy hunting is banned) and Tanzania, where wildlife laws allow for trophy hunting on auctioned wildlife-rich blocks, for foreign hunters who can afford a premium safari package.

“The targeted elephants were among the largest, oldest bulls,” a group of conservationists wrote in a letter decrying their loss, which was published in the journal Science in June. They represented “one of the last gene pools for enormous ivory and the source of the largest tusks ever collected”.

This month, the Tanzanian government will decide whether to issue more super-tusker hunting permits for the coming year. The authors urged them not to do so, and focus instead on ecotourism. “Alive, these super tuskers have great biological, economic and social value,” they wrote. “Once they are shot, their contribution ends.”

Jackson Mwato was born near Amboseli and grew up watching elephants roam around his home. “These tuskers are dear to the Maasai. We have coexisted with them for ages. They don’t know any international borders and some of our clans are named after them,” he says. Mwato is executive director of the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust that brings together conservancies covering 158,000 hectares (390,000 acres), and says the loss of the big tuskers could affect more than 65,000 households who rely on tourism. “If they disappear, it will be a loss to the country and the Maasai community.”

The tuskers belong to a population of 2,000 involved in the 51-year-old Amboseli Elephant Research Project, the longest study of elephants in the world. Conservationist Joyce Poole, co-founder of Elephant Voices and lead author of the letter protesting against their deaths, says the elephants’ “uniqueness” as scientific subjects should be protected.

Additionally, she says, those killed were “keystone” individuals, which younger males learn from and which coordinate the movements of closely bonded animals. “People who talk about hunting not having an impact or endangering elephant society, are only looking at it from numbers,” Poole says. “They’re not looking at how those individuals have a role in society.”

Audrey Delsink, wildlife director of the Humane Society International, agrees, describing these animals as “living icons” with “immeasurable” tourism value.

But other scientists say many who oppose hunting seem to push for bans even if they harm habitats, wildlife and communities. “However distasteful many may find hunting, it can and does work as a provider of revenue for conservation and communities,” says Prof Adam Hart from the University of Gloucestershire, co-author of the book Trophy Hunting.

Evidence shows that abolishing trophy hunting – and the incentives it creates for conservation – without funded alternatives can lead to greater loss of wildlife. Some studies have found that habitats managed for hunting can protect many other endangered species nearby.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has concluded there is “substantial evidence” trophy hunting produces positive outcomes for wildlife conservation. In 2017, the organisation said trophy hunting was “increasingly under intense scrutiny and facing high-profile and often effective campaigns calling for broad-scale ban” which “could hasten rather than reverse the decline of iconic wildlife, remove the economic incentives for the retention of vast areas of wildlife habitat, and alienate and undermine already marginalised communities who live with wildlife”.

A Tanzanian tour operator, who spoke on condition of anonymity and has hosted hunting parties for decades, says for local people, the benefits of trophy hunting far outweigh the losses.

He says: “You have someone paying $5,000 for a licence and about $10,000 for the trophy. Leasing a whole block could be as much as $60,000. Is that not creating employment for local people and ploughing back the money to conservation? One hunting camp employs close to 30 local people.”

He says hunters must be accompanied by anti-poaching personnel – increasing the range of patrols – and that they picked off old animals. “If my cow gets old, I normally sell it to a butcher or slaughter it myself. Likewise, would you rather not get top dollar from an animal that would have died of old age anyway?”

Amy Dickman, professor of wildlife conservation at the University of Oxford, said the argument is a microcosm of a much wider debate about the unintended harms of hunting bans. Focusing on the “scientific value” of the bulls perpetuated the idea that elephants and researchers were more important than local people, she says. “The letter follows the damaging pattern of demanding that hunting ends now, while providing no immediate alternative revenue stream,” she says. “[It] failed to even mention local communities.

“People don’t care as much about unintended consequences,” she adds. “[They] assume if you just ban something, then those animals will live in harmony in that place. It’s often not the case.”

For some scientists, these elephants’ age, distinctiveness, and our growing understanding of the complexity of their communication make the losses particularly difficult. Poole has been studying the Amboseli population since 1975 and over the decades, her research has revealed how sophisticated their communication is, including a paper last month that found elephants have names for one another. “My heart goes out to them, because they are just such incredible animals,” she says.