The Texas blackouts showed how climate extremes threaten energy systems across the US.

Pundits and politicians have been quick to point fingers over the debacle in Texas that left millions without power or clean water during February’s deep freeze. Many have blamed the state’s deregulated electricity market, arguing that Texas prioritized cheap power over reliability.

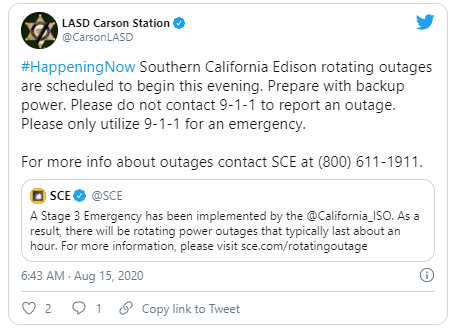

But climate extremes are wreaking increasing havoc on energy systems across the U.S., regardless of local politics or the particulars of regional grids. For example, conservatives argued that over-regulation caused widespread outages in California amid extreme heat and wildfires in the summer of 2020.

As an engineering professor studying infrastructure resilience under climate change, I worry about the rising risk of climate-triggered outages nationwide. In my view, the events in Texas offer three important lessons for energy planners across the U.S.

Not enough attention to climate extremes

Experts widely agree that the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, or ERCOT, the nonprofit corporation that manages the power grid for most of the state, failed to anticipate how sharply demand would spike prior to the February cold wave. ERCOT has a record of lacking capacity to meet winter demand surges. The state grid nearly collapsed during a 2011 winter storm and experienced another close call in 2014, narrowly avoiding rolling blackouts.

But grid operators elsewhere have also underestimated how climate extremes can influence electricity demand. I see many similarities between California’s summer 2020 power crisis and recent events in Texas.

In both cases, extreme weather caused an unexpected increase in demand and reduced generation capacity at the same time. Because energy operators did not foresee these effects, they had to resort to rolling blackouts to avert even bigger disasters.

In studies I have conducted in my research lab and in collaboration with hydroclimatologist Rohini Kumar, we have found that energy planners in many parts of the U.S. substantially underestimate how sensitive electricity demand is to climate factors. This tendency has significant implications for the security and reliability of the power systems.

For example, in a study published in April 2020 we analyzed the use of artificial intelligence models for energy forecasting that accounted for the role of humidity in addition to air temperature. We found that such models could make forecasts of energy demand for air conditioning on hot days significantly more accurate across the U.S. More accurate demand forecasts help energy planners understand how much power they will need to meet peak demand during weather extremes.

Grid operators can prepare more effectively for the effects of climate change on both supply and demand by using forecasting models and software that academic researchers have already developed. Many of these new solutions have been published in open-access journals.

Water, electricity and natural gas are connected

Electricity, water and natural gas are essential resources, and it’s hard to have any of them without the others. For example, drilling for natural gas consumes electricity and water. Many power plants burn natural gas to generate electricity. And transporting water and gas requires electricity to pump them through pipelines.

Because of these tight connections, outages in one system are bound to ripple through the others and create a cascade of service disruptions. For example, during the Texas cold wave, pumps used to extract gas in West Texas could not operate because of electricity outages. This cut state gas field production in half, which in turn strained gas-fired electricity production. Power failures also hampered water pumping and treatment, potentially allowing bacteria to seep into water supplies.

In a collaborative project connecting researchers at Purdue University, the University of Southern California, and the University of California-Santa Cruz, we are analyzing ways to prevent this kind of cascading outage. One promising strategy is to install distributed generation sources, such as solar panels or small wind turbines with batteries, at critical interconnection points between energy, water and natural gas systems.

For their part, consumers also need to understand these connections. Taking a hot shower or running a dishwasher consumes water, along with electricity or gas to heat it. These crunch points often cause trouble during crises. For instance, recent advisories urging Texans to boil their water before using it put extra pressure on already-scarce energy supplies.

Our research shows that utilities need to pay more attention to connections between natural gas and electricity, and between water and electricity. By doing so, planners can see more accurately how climate conditions will affect demand, particularly under climate change. Rampant gas shortages and electricity and water outages in Texas are a sign that infrastructure operators need to understand more clearly how tightly related these resources are, not only during normal operation but also during crises that can disrupt all of them at once.

The future will be different

Some commentaries on the Texas disaster have called it a “black swan event” that could never have been predicted – or even worse, a “meteor strike.” In fact, the state published a hazard mitigation plan in 2018 that clearly warned of the potential for severe winter weather to cause widespread outages. And it noted that such events would be far more disruptive in Texas than in other regions that experience harsher winters.

In a 2016 study, several colleagues and I warned that current grid reliability metrics and standards across the U.S. were inadequate, especially with respect to climate risks. We concluded that those standards “fail to provide a sufficient incentive structure for the utilities to adequately ensure high levels of reliability for end‐users, particularly during large‐scale climate events.”

As I see it, a dominant paradigm of “faster, better, cheaper” in energy planning is placing increasing pressure on our nation’s aging infrastructure. I believe it is time for energy planners to be more proactive and make smart investments in measures that will help power systems handle extreme weather events.

Key steps should include leveraging predictive analytics to inform disaster planning; accounting for climate uncertainty in infrastructure management; upgrading reliability standards for power transmission and distribution systems; and diversifying the mix of fuels that all states use to generate electricity. Without such steps, frequent disruptions of critical services could become the new norm, with high costs and heavy impacts – especially on the most vulnerable Americans.

2 March 2021

THE CONVERSATION