Record-shattering heat wave bakes western US, raising drought and fire concerns

Summer has yet to officially begin and temperatures are soaring, bringing bad air quality and worsening the mega-drought

This week the temperatures hit 106F (41C) in Billings, in southern Montana. In Arizona, animals were scorching their paws on blistering asphalt. In Texas, authorities asked residents to limit cooking and cleaning to preserve a creaking power grid.

These were just some of the scenes emerging from one of the most excruciating heatwaves to ever hit the western United States this early in the year. From California to Montana, a staggering 40 million people are experiencing temperatures of 100F (38C) or hotter this week, and 50 million were under excessive heat warnings and heat advisories.

The soaring temperatures have stressed power systems, with grid operators urging residents to conserve energy in order to avoid triggering brownouts or outages. On Thursday, California governor Gavin Newsom an emergency proclamation, the “extreme heat peril”, that allows power plants to ramp up operations quickly to meet energy demands as people across the state crank up their air conditioning.

Wildfires have sparked across the hot, dry south-west, with lightning and gusty winds threatening to spark more. The extreme heat and deepening regional drought have complicated firefighters’ efforts to contain the blazes. In Arizona, some large aerial tankers used to fight fires were unable to fly due to the high temperatures. And the drought had diminished water supplies, leaving crews scrambling for water.

For many it is merely a hint of things to come as the planet warms amid the global heating crisis and such extreme events become more and more common.

Many cities across the American west have opened cooling stations and hydration stations to keep people safe from the dangerous temperatures – and the hottest months of the year are still expected to come.

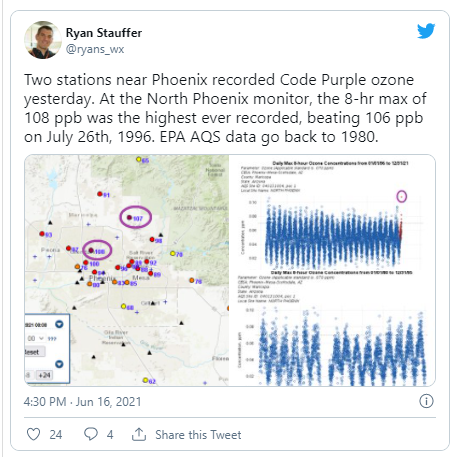

The heat also added to smoggy air conditions, the worst in years in some locations. On Tuesday, areas around Phoenix saw the worst air quality since data started being recorded in 1980, tweeted Ryan Stauffer, an air quality expert at Nasa.

This mega-heatwave is being pumped up by climate breakdown, researchers say. “Currently, climate change has caused rare heatwaves to be 3 to 5 degrees warmer over most of the United States,” Michael Wehner, a climate scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, wrote in an analysis published Tuesday, adding that heatwaves are likely to get worse in the future.

In addition to extreme heat, the conditions are further worsening a mega-drought already impacting the region that is drying up rivers, threatening salmon stocks and seeing reservoir levels plummet. On Wednesday, America’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead, registered its lowest level on record since it was filled in the 1930s. In northern California almost 17m salmon are now being taken to the sea in a fleet of trucks as their river habitats dry up and the water becomes too hot for them to survive.

“One could not have wished for a more perfect storm created by humans,” said Stephanie Pincetl, who directs the California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA, of the current crisis in heat and drought.

According to the US Drought Monitor, more than 55% of the west is experiencing “extreme” or “exceptional” drought conditions. Water in soils is at a historic low point, meaning there’s little moisture to absorb the heat – instead, the land is baking like an oven and creating even hotter conditions.

Karen McKinnon, a climate researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, published research in the journal Nature Climate Change on Thursday showing that since 1950, humidity across the non-coastal south-west United States on dry days has dropped significantly – 22% on average, and 33% in California and Nevada. That is important as low humidity levels can spur the west’s other environmental disaster-in-waiting: wildfires.

Falling humidity levels mean more high-risk wildfire days, and the dry air draws more moisture from vegetation, making it even more flammable and contributing to tree mortality, she says. “We already have these dry soils and high vegetation dryness, which is a major predictor of wildfire.”

Since Sunday, wildfires have erupted in states from California to Wyoming, and conditions are ripe for more.

“The west is on the losing side of the battle here,” says Imtiaz Rangwala, a climate scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

He says that wildfire risk comes down to three things: dry, windy weather (often called fire weather), dry fuels and an ignition source. “When you have the first two pieces coming together, it’s just a matter of time until the human-caused ignition happens,” he says.

McKinnon says there are ways to dampen the effects of a heatwave on dense, urban environments – which are often communities of color – where the so-called urban heat island effect can make high temperatures even more oppressive by reflecting heat on to sidewalks. For one, cities can plant more trees, which help lower temperatures. “Not only do they provide shade but also evaporative cooling,” she says.

Imagining a future in a drier, hotter west means looking at different sets of values, says Pincetl. To become more sustainable, cities need to stop suburban sprawl and focus on density and public transportation in cities – a lower-carbon way of living. “It’s about sufficiency – it’s about enough. Enough to eat, enough energy for the washing machine. It’s about thinking about the limits of the planet,” she says.

“Climate change is a human engineered change, fire suppression is a human thing too. I find it a little thin to say ‘Oh, the climate is doing this’ – it’s really a result of our activities and decisions.”

Climate models show a warming trend for at least the next 30 years – and in some parts of the west in America it will be a serious amount. Globally, temperatures are expected to rise about 2F (about 1C) and in the American west it’s closer to 2-4F (1-2C) – and as much as 5F (nearly 3C) in some places. Some parts of Colorado have already warmed double the average, Rangwala says. “We have climate change in the pipeline,” he says, “and there’s not much we can do about it in the short-term. But we can stabilize later on.”

Rangwala points to recent die-offs of 350m pinyon trees in the south-west as evidence that ecosystems are changing on a large scale, and it’s still not clear where the tipping points are for broad change – or in what state the systems will stabilize.

“We’re already in a new normal and the new normal is going to get worse in terms of how much water we have, and the resources we need to sustain our current way of living,” he said.