Ratchets, phase-downs and a fragile agreement: how Cop26 played out

Last-minute hitch on coal almost reduced Alok Sharma to tears as Glasgow climate pact made imperfect progress

As weary delegates trudged into the Scottish Event Campus on the banks of the Clyde on Saturday, few realised what a mountain they still had to climb. The Cop26 climate talks were long past their official deadline of 6pm on Friday, but there were strong hopes that the big issues had been settled. A deal was tantalisingly close.

The “package” on offer was imperfect – before countries even turned up in Glasgow they were meant to have submitted plans that would cut global carbon output by nearly half by 2030, to limit global heating to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. Although most countries submitted plans, they were not strong enough and analysis found they would lead to a disastrous 2.4C of heating.

The gap between countries’ targets and the emissions cuts scientists say are needed had been known since before the start of the talks – what was crucial in Glasgow was to find a roadmap to closing it, which involved forcing some highly reluctant countries to agree a timetable of swift revisions. Finally, after two weeks of wrangling, a “ratchet” had been settled, with countries agreeing to return next year, and the year after, with amendments.

As the Cop president, Alok Sharma, approached the podium, the gavel was poised by his folder, ready to push through an agreement between all of the nearly 200 countries gathered in the room. But there was a last-minute hitch.

What followed reduced Sharma almost to tears. China and India wanted to reopen a vital clause in the agreement that enjoined countries to “phase out” coal-fired power generation. No dates were given for the phaseout, and no more commitment than “accelerating efforts towards the phaseout of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”.

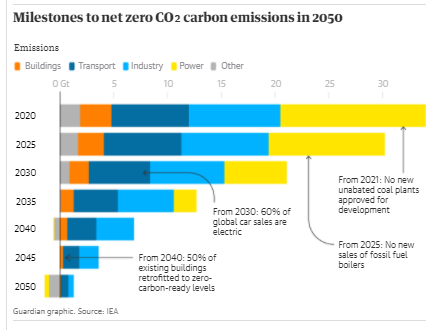

Abandoning coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel, is essential to staying within 1.5C, the most stringent goal under the 2015 Paris climate agreement, and a level scientists regard as a planetary boundary beyond which some of the impacts of climate breakdown will become catastrophic and irreversible. The International Energy Agency has said 40% of the world’s existing 8,500 coal-fired power plants must be closed by 2030, and no new ones built, to stay within the 1.5C limit.

Sharma had made “consigning coal to history” a personal mission through his presidency of the UK talks, and made numerous speeches on it. He had determined long before the start of the summit that he wanted a commitment on coal in the text.

It may seem uncontroversial for an agreement on the climate to refer to the need to cut out fossil fuels, as they are the source of the problem. Yet since the Kyoto protocol was signed in 1997, there has been no such reference in a Cop decision, at the behest of the major fossil fuel producers and users, who hold a great deal of sway in a process that relies on consensus. The inclusion of such a commitment in the Glasgow outcome was thus a major step.

At the last minute, China and India made it known that they objected to this wording. Sharma, who had been surviving the day on a diet of Lucozade tablets as he had no breaks for food, convened a meeting in the space behind the auditorium. The two countries – both major coal users and producers – would not accept the current wording. As the Indian delegates discussed the wording among themselves, Sharma answered them in Hindi to press the case for its retention – but to no avail. The two countries were adamant: a phaseout was unacceptable; but a phase-down, implying a longer-term future for some coal at least, was the most they would sign up to. The carefully crafted agreement was now in peril.

“My fear was we would lose the whole deal,” he told the Guardian later. “This was a fragile agreement. If you pull one thread, the whole thing could unravel. We would have lost two years of really hard work – we would have ended up with nothing to show for it, for developing countries.”

The man jokingly nicknamed “No Drama Sharma” by his team was on the verge of tears. To be forced to accept the change was bitter, and he was “deeply frustrated” according to an aide, but said it was the only way to protect the overall deal.

Sharma has seen himself from the start as the champion of the most vulnerable developing countries at these talks, the only forum in which the poorest nations can confront the biggest emitters and producers of fossil fuels with the consequences of their actions. Choking back emotion, he addressed them directly: “I apologise for the way this process has unfolded. And I am deeply sorry. I also understand the deep disappointment. But as you have also noted, I think it’s vital that we protect this package.”

Developing countries felt the disappointment just as keenly, but they understood the difficulties Sharma faced. “Although this is far from a perfect text, we have taken important steps forward in our efforts to keep 1.5C alive, and deliver the much-needed outcomes on adaptation,” said Milagros de Camps, of the Dominican Republic and the Alliance of Small Island States. “We acknowledge it was not an easy task.”

The last-minute change of wording was galling, but did not materially change the agreement. Sharma insists that the deal as it stands shows “we are on the way to consigning coal to history”, and Nicholas Stern, the peer and climate economist, concurs: “The last-minute watering down of this statement is unfortunate but is unlikely to slow down a strong momentum past coal, a dirty fuel of an earlier era.”

John Kerry, the UN climate envoy, was also visibly annoyed, telling journalists afterwards: “Did I appreciate we had to adjust one thing tonight in a very unusual way? No. But if we hadn’t done that we wouldn’t have a deal. I’ll take phase it down and take the fight into next year.”

When countries meet next year, it will be very hard for any to rewrite the commitment now that it has been adopted. For the UK, it was a bitter pill but did not scupper the hard-fought diplomatic struggle to “keep 1.5C alive”.

Returning to the ‘ratchet’

Agreeing to return next year to revise countries’ emissions targets may not sound like much of an achievement. But climate talks sometimes seem to move at the rate of a pre-industrial glacier. The UN climate Cops have been taking place almost annually since 1992, when the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, parent treaty to the Paris agreement, was signed.

For most of that time, countries squabbled over who should have to cut greenhouse gas emissions and how. Meanwhile, carbon counts kept rising.

The Paris agreement of 2015 marked the first time that developed and developing countries agreed to take the necessary action to limit temperature rises, to “well below” 2C above pre-industrial levels, and to “pursue efforts” to limit heating to 1.5C.

However, while the Paris treaty set the binding targets, the means to get there were contained in a non-binding annexe. These national plans on cutting emissions, called nationally determined contributions (NDCs), were drafted and presented by each country but they were much too weak to achieve the temperature goals – under the Paris NDCs, temperatures would soar by more than 3C, enough to swamp most of the world’s major coastal cities.

So the accord also contained a mechanism to force countries back to the table. Informally known as the “ratchet”, this would require all signatories to return with revised NDCs every five years. That is why Cop26 was always going to be so important – it marked the first five-yearly revision (it was supposed to take place in November 2020 but was delayed by a year because of the Covid-19 pandemic).

Since the Paris agreement was signed, however, scientific warnings on climate breakdown have intensified. In October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – the world’s leading authority on climate science – produced a report showing that going beyond 1.5C would produce changes to the climate system that would rapidly become irreversible. The melting of the ice caps would accelerate, sea levels would rise to inundate small islands and coastal areas, coral reefs would bleach and extreme weather such as droughts, floods, heatwaves and fiercer storms would wreak havoc.

Johan Rockström, the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and one of the world’s foremost climate scientists, warned that the 1.5C target was not like other political negotiations, which can be haggled over or compromised on. “A rise of 1.5C is not an arbitrary number, it is not a political number. It is a planetary boundary,” he told the Guardian in an interview. “Every fraction of a degree more is dangerous.”

These warnings, repeated in an IPCC report this summer, showed that the Paris timetable was too loose. To have a good chance of staying within 1.5C, the IPCC estimated, greenhouse gas emissions must fall by about 45% by 2030 compared with 2010 levels, and reach net zero by mid-century. Except for a short blip during the lockdowns, carbon emissions have been steadily rising since the Paris agreement was signed.

When the UK took over the Cop26 presidency, countries were still in the early process of preparing their NDCs. Under the Paris agreement, they had no obligation to align them with the IPCC advice on halving by 2030 – just a looser obligation to strive to meet the Paris temperature goals. Sharma and his advisers decided that the conference must have a clearer objective – to focus attention not on the “well below 2C” limit, but on the tougher but far safer 1.5C. And if the NDCs that were presented were not good enough, countries would have to return not every five years as envisaged at Paris, but every year until they were good enough.

That is because this decade is now crucial, according to scientists. António Guterres, the UN secretary general, warned after the latest IPCC findings in August: “[This report] is a code red for humanity. The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable: greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel burning and deforestation are choking our planet and putting billions of people at immediate risk.”

Yet at Glasgow some countries tried to claim that focusing on 1.5C and forcing a review of NDCs next year was an attempt to “reopen the Paris agreement”. Sharma was forced to deny this repeatedly: “We are not seeking to reopen the Paris agreement. The Paris agreement clearly sets out the temperature goal well below 2C and pursuing efforts to 1.5C. That is why our overarching goal of keeping 1.5C within reach has been our lodestar.”

According to its architects, the Paris agreement was carefully written to be supple enough to allow for yearly returns, under provisions in article 4 of the accord. In the closing stages of the Cop26 talks, the trio behind the agreement – Laurent Fabius, the French foreign minister who presided over the talks; his chief diplomat, Laurence Tubiana; and Christiana Figueres, the former UN climate chief – told the Guardian it was “essential” for countries to meet again next year to fulfil the terms of the Paris accord.

“If that [five years] is the first time that countries are called to increase their ambitions, honestly that’s going to be too late,” said Figueres, founding partner of the Global Optimism thinktank.

Forcing countries back to the table also provides the sort of pressure that countries need to feel in order to make the commitments needed, according to Tom Burke, a veteran government adviser who is co-founder of the E3G thinktank. “You need an anvil, as well as a hammer,” he said. “The anvil is that moment of pressure – a big event, like a Cop.”

Cops have another advantage: they are the only forum in which the smallest developing countries have an equal say with the largest economies. At Cop26, more than 30,000 participants from nearly 200 countries roamed the halls, some in colourful national dress, others in sombre suits, all – this time – in masks. In these meetings, the people suffering on the frontlines of the climate crisis have an opportunity to directly confront those responsible for the emissions causing climate change. It is a powerful moral lever, notes Tina Stege, climate envoy for the tiny Marshall Islands, an archipelago with 60,000 inhabitants that leads the High Ambition Coalition at the talks. “We are a small nation, but we have moral authority – our position on the frontline gives us that,” says Stege. “We need to raise our voice, as these changes will affect the whole world in time.”

The final stages of the Cop26 talks bore this out: Tuvalu’s representative received resounding applause for noting that his island would be under water if the talks failed, and Kenya for noting that a 1.5C global temperature rise would equate to an unbearable 3C rise in parts of Africa.

For these reasons, the agreement to return next year to revise NDCs is far more important and powerful than it may at first appear. Stege said: “It is real progress, and elements of the Glasgow package are a lifeline for my country. We must not discount the crucial wins covered in this package.”

Taking the lead

Under the UN rules, Sharma will remain Cop president for the next year. That gives a clear opportunity for the UK to show leadership on the climate crisis before next year’s crucial meeting in Egypt, and to gee up countries to make further cuts in their emissions in line with a 1.5C target. “We will have a very active presidency,” he pledged to the Guardian as he left Glasgow by train. “Everyone who knows about these talks know that this is not about one big bang solution to climate change. It’s a building block.”

But if the UK is to make such a mark, and help lay the crucial groundwork for a successful conclusion to next year’s Cop, much of that work will need to start at home. At Cop26, the UK government led a series of initiatives – on banking, forests, coal and electric vehicles – that failed to impress some observers, who worried they were motivated by greenwash.

The forest announcement, involving a pledge to halt deforestation by 2030, was criticised as a repeat of a previous failed attempt; the 450 banks who signed up to net zero pledges turned out to be allowed to continue investing in fossil fuels; the world’s biggest coal users were left out of the much-vaunted promise to phase out coal; and major car manufactures shunned the electric vehicle pledge.

Mohamed Adow, of the thinktank Power Shift Africa, complained: “These announcements are eye candy, but the sugar rush they provide are empty calories.”

Campaigners and green experts have also been dismayed by the government’s habit of continuing to support high-carbon policies and developments, even while trumpeting its low-carbon credentials. They point to decisions such as the mooted Cumbrian coalmine; new oil and gas licences in the North Sea; cuts to air passenger duty; road-building and airport expansion; and most of all the cuts to overseas development aid, which have undermined the crucial message on climate finance to the developing world at Cop26.

Rachel Kennerley, climate campaigner at Friends of the Earth, said: “The UK government cunningly curated announcements throughout this fortnight so that it seemed rapid progress was being made. With the Cop moment over, countries should break away from the pack in their race for meaningful climate action and let history judge the laggards.”

If the UK wants to “follow through” the achievements made at Cop26, these are the policies on which ministers need to start. Otherwise, Sharma’s two years of hard work may still prove fragile and prone to unravel.

15 November 2021

The Guardian