Landmark ban on CFCs in 1980s prevented deadly ‘scorched Earth’ scenario, research reveals

Scientists paint apocalyptic vision of soaring temperatures and catastrophic impacts on agriculture without signing of crucial Montreal Protocol

On 16 May 1985, three scientists from the British Antarctic Survey published shocking findings in the respected journal Nature: They had detected abnormally low levels of ozone in the stratosphere over the South Pole.

This crucial protective layer around our planet blocks much of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation, which can cause skin cancer in humans, and can restrict plant growth, damaging their tissues and impairing their ability to absorb carbon.

Such was the seriousness of the discovery of the widening hole – which had already been linked to the use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in aerosol sprays, fridges and airconditioning systems – that within just two years, 46 nations signed the historic Montreal Protocol, to phase out the substances.

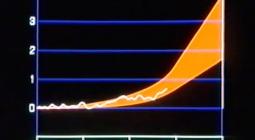

New research has revealed just how critical the international accord was. Modelling by an international team of scientists from the UK, US and New Zealand, published today, also in Nature, has found that if CFCs had not been banned in the late 1980s, their continued use would have contributed to average global air temperatures rising by an additional 2.5C by the end of the century.

That 2.5 figure would have been on top of whatever warming is already locked in and also still being caused by emissions of other greenhouse gases.

“We would be facing the reality of a ‘scorched Earth’” scenario, the research team said, in a dramatic vision they described as the “world avoided”.

Dr Paul Young, from Lancaster University and the lead author of the research, told The Independent “it would likely have been pretty catastrophic”.

The return of the ozone layer following the CFC ban has served to protect plants’ ability to soak up and lock in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, thereby preventing a further acceleration of the climate crisis.

Dr Young said that by 2050, “the uptake of carbon by plants and trees would have been less than half as much in the world avoided compared to the world that we are living in”.

He said: “By the end of the century, carbon uptake in the world avoided would have been less than 15 per cent the amount with CFCs controlled.”

“I think it’s safe to imagine that plants and trees would at least be far more stunted than they are now.”

To study just how effective the CFC ban has been, the research team developed a new modelling framework, bringing together data on ozone depletion, plant damage by increased UV, the carbon cycle and impact of the climate crisis.

This modelling revealed:

- Continued growth in CFCs would have led to a worldwide collapse in the ozone layer by the 2040s.

- By 2100 there would have been 60 per cent less ozone above the tropics. This depletion above the tropics would have been worse than was ever observed in the hole that formed above the Antarctic.

- By 2050 the strength of the UV from the sun in the mid-latitudes, which includes most of Europe including the UK, the United States and central Asia, would be stronger than the present day tropics.

Dr Young told The Independent: “While it was originally intended as an ozone protection treaty, the Montreal Protocol has been an extremely successful climate treaty. It has not only controlled the emissions of highly potent greenhouse gases but, as we show, through protecting plants and the land carbon sink, has led to avoided additional CO2 increases.”

The researchers said without the protocol the impacts would have meant that by 2100, there would be 580 billion tonnes less carbon stored in forests, other vegetation and soils, and there would be an additional 165-215 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere, depending on the future scenario of fossil fuel emissions.

Compared to today’s 420 parts per million CO2, this is an additional 40-50 per cent.

As our planet has already seen 1C warming since pre-industrial temperatures, even if we had somehow managed to get to net zero CO2 emissions, the additional 2.5C rise without the CFC ban would take us to a rise of 3.5C.

This is far in excess of the 1.5C rise above pre-industrial levels that many scientists see as the most global temperatures can rise in order to avoid some of the most damaging effects of climate change.

Dr Chris Huntingford of the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology said: “This analysis reveals a remarkable linkage, via the carbon cycle, between the two global environmental concerns of damage to the ozone layer and global warming.”

Asked what the world might have looked like if the countries had been unable to come to an agreement, Dr Young said: “It’s a exercise for the imagination about what it would have been like - would we be permanently caked in suncream, wearing wide-brimmed hats and sunglasses, and only outside for 10 minutes a day?

“Or would we have realised that something was amiss around 2040 and then took drastic steps to halt CFC emissions? Would that even be easy by then, given their - no doubt - widespread use?”

But he warned that while the international community was able to come together and take rapid action in the case of CFCs, the process is not directly comparable to the current effort to reduce use of the other greenhouse gases.

He said: “While it’s tempting to see the parallels with climate negotiations, we must remember that the Montreal Protocol was dealing with a handful of chemicals, made by a handful of companies, and for which there were replacements readily available. Despite some resistance from the companies, and the existence of some cranks denying the evidence, the ozone layer issue was ultimately a tractable one.

“Fossil fuels, on the other hand, are a far more complex issue, whose use permeates our lives more deeply and whose reduction will not just be a straight swap with another chemical.”

“Of course, that is not to say that we shouldn’t rise to the challenge - we must! Perhaps the hope from the Montreal Protocol is that it has been a tremendous success story: science identified a threat and the world agreed and acted on that threat.”

19 August 2021

INDEPENDENT