How plans for new coal are changing around the world.

Just 15 countries dominate the pipeline for new coal. Together, they are responsible for 90% of coal capacity under development. This guest post explains what is happening in each of these key countries - and a few others - based on Global Energy Monitor's latest Global Coal Plant Tracker.

Start Exploring Here.

The global coal fleet continues to grow in 2019 but the pipeline shrank again, putting a peak in total operating capacity on the horizon.

Just 15 countries are responsible for 90% of this shrinking pipeline, with each facing different political, social and economic pressures, incentives and trends. This guest article explains what is going on in each of the 15 key countries (see map, above) and then offers a global overview of the situation, based on Global Energy Monitor’s latest Global Coal Plant Tracker.

(Carbon Brief used the data from the February edition of the tracker to produce a global coal plant map and timeline.)

Around the world, 12.7 gigawatts (GW) of new coal capacity has been proposed so far in 2019 – less than 3GW above the amount that has retired (10GW). These trends mean the global coal fleet will soon decline, because only a third of proposed capacity has actually been developed since 2010.

While the pipeline for new coal plants is shrinking, however, enough have already been built – when combined with other fossil fuel infrastructure – to use up the entire carbon budget for 1.5C. The length of time and rate at which existing coal plants operate is therefore a key determinant of whether global climate goals can be met.

Shrinking pipeline

The UN’s secretary-general António Guterres has called for a global moratorium on new coal plants being built after 2020, to help meet international climate goals. His call currently looks unlikely to be fulfilled, even though the global pipeline for new coal capacity is shrinking.

In 2019 to date, about 12.7GW of coal power capacity has been newly proposed across eight countries and 12GW of new construction has started across five countries.These developments are concentrated in China, India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Bangladesh. China also resumed construction on nearly 9GW of capacity that had been postponed under central government restrictions.

Conversely, 132GW of planned new capacity was cancelled in 2019, mainly from lack of activity. The largest numbers of cancellations were in China, India, Myanmar and Turkey.

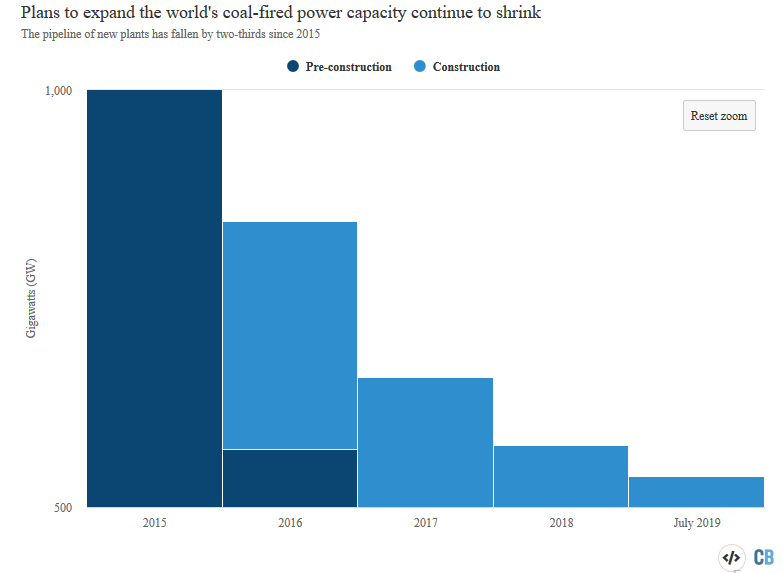

Overall, coal capacity under development totaled 538GW in the first half of 2019, including 227GW being built (dark blue chunks in the chart, below) and 311GW in earlier stages (light blue). This total is down 6% from the end of 2018 and 62% since 2015.

Despite this shrinking pipeline, the global coal fleet increased by 17GW in the first half of 2019, net of retirements. New capacity remains highly concentrated: nearly 85% (23GW) of the 27GW commissioned in 2019 was in China (17.9GW) or India (4.8GW).

The other 11 countries that commissioned coal-fired capacity in 2019 added less than 1GW each. Meanwhile over 10GW of capacity was retired in 2019, led by the US (6.4GW) and European Union (2GW). To date, 2019 is on track to be the fourth highest year for coal plant retirements on record in the US.

Dominating development

Some 15 countries make up 90% of all coal capacity currently under development around the world (486GW of 538GW). China and India alone comprise over half the total (281GW, or 52%). See the map at the top of the article for more details of developments in each of these 15 key nations, along with a few others.

The 15 countries and their shares of the global total are listed in the table below. The table includes the “implementation rate” – the percentage of planned capacity that has begun construction or been commissioned since 2010, versus the amount that has been shelved or cancelled.

The implementation rate figure in the table above varies widely, from 0% in Egypt – which has yet to implement any of its projects – to 71% in South Korea. The global average is 35%, meaning just 1GW of new coal has been built or began construction since 2010 for each 3GW of proposed capacity.

China continues to push forward with previously postponed coal plants (see the map above for more detail). However, new proposals are slowing and existing coal plants have been running only around 50% of the time since 2015 on average, indicating a large excess of capacity.

India has undergone a large downscaling in its future coal plans, in favour of lower-cost renewables. Turkey has 34GW of coal in the pipeline, but has commissioned only 12% of its proposed capacity since 2010 – a rate that would lead to only 4GW of the 34GW being completed. In reality, the figure may ultimately be even lower than this.

Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have all reduced their proposed coal capacity, with no new large proposals since 2015. Meanwhile Japan and Korea are also facing public pressure to cut their international financial support for coal, which would leave only China as a significant source of global coal funding – given over 100 financial institutions are restricting coal financing.

Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, and Pakistan have all scaled back plans for coal in their future national energy plans, with many of them experiencing significant coal-related financial problems.

Poland also looks unlikely to expand its coal proposals, given the sustained political and legal pressure over its current projects. In South Africa, numerous financial problems and delays to its proposed new capacity have led future projects being suspended under its coal Independent Power Producer (IPP) program – although construction continues on state-backed projects.

The vast majority of proposed capacity in Egypt, Russia and Mongolia consists of a single, large coal plant in each country, all three of which are reliant on Chinese financing.

Only Bangladesh and the Philippines have either maintained or grown their planned new coal projects in 2019. Both will also need costly new or expanded infrastructure to import the coal for these power stations. President Duterte of the Philippines recently called for the fast-tracking of renewables to reduce national dependency on coal imports.

Finally, Australia’s newly elected pro-coal government is also pursuing new coal plants, despite unfavorable economics.

Concentrated coal

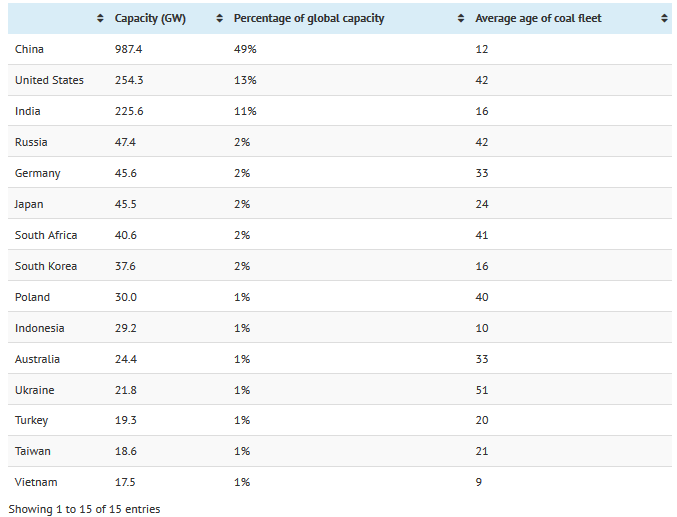

Like proposed coal capacity, operating power stations are highly concentrated. Some 15 countries – shown in the table, below – make up 91% of the global total (1,845GW of 2,027GW).

China alone comprises nearly half (49%) of the global coal fleet, with 987.4GW, followed by the US with 13% (254.3GW) and India with 11% (225.6GW). The average age of the countries’ coal fleets range from 9 years (Vietnam) to 51 years (Ukraine).

Unabated coal power generation falls by 55-70% by 2030 and is effectively phased out by 2050 in pathways outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change last October for limiting global temperatures to no more than 1.5C above pre-industrial temperatures – the aspirational goal of the Paris Agreement.

As the pipeline for new coal dries up and older capacity reaches retirement, the lifetime and running hours of the world’s younger coal plants will therefore be a key determinant of whether global climate goals can be met.

*Dr Christine Shearer is a researcher and analyst for the US-based energy research group Global Energy Monitor.

CarbonBrief